Heart Failure due to Critical Aortic Stenosis Case File

Eugene C. Toy, MD, Gabriel M. Aisenberg, MD

Case 4

A 72-year-old man presents to the clinic complaining of worsening exertional dyspnea. Previously, he had been able to work in his garden and mow the lawn, but now he feels short of breath after walking 100 ft. He does not have chest pain at rest but has experienced retrosternal chest pressure with strenuous exertion. He occasionally feels light-headed while climbing a flight of stairs, as if he were about to faint, but this resolves after sitting down. He now uses three pillows when he sleeps; otherwise, he wakes up at night feeling short of breath, which is relieved within minutes by sitting upright in bed. He notes occasional swelling of his lower extremities. He denies any significant medical history, takes no medications, and prides himself on the fact that he has not seen a doctor in years. He does not smoke or drink alcohol.

On physical examination, he is afebrile, with a heart rate of 86 beats per minute (bpm), blood pressure of 115/92 mm Hg, and respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute. Examination of the head and neck reveals a normal thyroid gland and distended neck veins. Bibasilar inspiratory crackles are appreciated. On cardiac examination, his heart rhythm is regular with a normal S1 and S2, with an S4 at the apex, a leftward displaced apical impulse, and a late-peaking systolic murmur at the right upper sternal border that radiates to his carotids. The carotid upstrokes have diminished amplitude.

▶ What is the most likely diagnosis?

▶ What test would confirm the diagnosis?

ANSWERS TO CASE 4:

Heart Failure due to Critical Aortic Stenosis

Summary: A 72-year-old man presents with

- Angina-like chest pressure with strenuous exertion and near-syncope while climbing a flight of stairs

- Orthopnea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, pedal edema, elevated jugular venous pressure (JVP), and crackles suggesting pulmonary edema

- A late systolic murmur radiating to his carotids, the paradoxical splitting of his second heart sound, and the diminished carotid upstrokes suggesting severe aortic stenosis

Most likely diagnosis: Heart failure (HF), likely as a result of aortic valve stenosis.

Diagnostic test: Echocardiogram to assess the aortic valve area as well as the left ventricular (LV) systolic function, chest x-ray, electrocardiogram (ECG), and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels.

- Identify the causes of chronic HF (eg, ischemia, hypertension, valvular disease, alcohol abuse, cocaine, and thyrotoxicosis). (EPA 1, 3)

- Understand the treatment of acute and chronic HF. (EPA 4)

- Discuss the evaluation of aortic stenosis and the indications for valve replacement. (EPA 1, 4, 7)

- Identify preventive measures for general patients at risk for heart failure (HF) to avoid progression. (EPA 4)

Considerations

This is an elderly patient with symptoms and signs of aortic stenosis. The valvular disorder has progressed from previous angina and presyncopal symptoms to HF, reflecting worsening severity of the stenosis and worsening prognosis for survival. This patient should undergo urgent evaluation of his aortic valve surface area and coronary artery status to assess the need for valve replacement.

APPROACH TO:

Heart Failure

DEFINITIONS

ACUTE HF: Acute (hours, days) presentation of cardiac decompensation with pulmonary edema and low cardiac output, which may proceed to cardiogenic shock; can be superimposed onto chronic HF.

CARDIAC REMODELING: Changes to cardiac myocytes due to changing cardiac parameters leading to cardiac dysfunction. Some medications can prevent or even reverse the remodeling.

CHRONIC HF: Chronic (months, years) presence of cardiac dysfunction; symptoms may range from minimal to severe.

DIASTOLIC DYSFUNCTION: Increased diastolic filling pressures caused by impaired diastolic relaxation and decreased ventricular compliance, but with preserved ejection fraction (EF) > 40% to 50%. Etiologies may include uncontrolled hypertension, constrictive pericarditis, restrictive cardiomyopathy, and cardiac tamponade, among others.

LEFT-SIDED HF: HF due to left ventricular dysfunction; also known as “forward” HF.

RIGHT-SIDED HF: HF due to right ventricular dysfunction; also known as “backward” HF.

SYSTOLIC DYSFUNCTION: Low cardiac output caused by impaired systolic function (low EF < 40%). Etiologies may include myocardial infarction, myocarditis, and dilated cardiomyopathy resulting from multiple diseases, among others.

CLINICAL APPROACH TO HEART FAILURE

Pathophysiology

Heart failure is found in 1% to 2% of the US population, with disproportionately higher rates in African Americans, Native Americans, and Hispanics. HF is a clinical syndrome that is produced when the heart is unable to meet the metabolic needs of the body while maintaining normal ventricular filling pressures. A series of neurohumoral responses develops, including activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis and increased sympathetic activity, which initially may be compensatory but ultimately cause further cardiac decompensation. The most common cause of HF overall is ischemic cardiomyopathy. Systolic dysfunction is classified via transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) by reduction of contractility (reduction in EF), in contrast to diastolic dysfunction, in which EF is preserved.

Clinical Presentation

Types of HF. Symptoms may be a result of forward failure (low cardiac output or systolic dysfunction), including fatigue, lethargy, and even hypotension, or backward failure (increased filling pressures or diastolic dysfunction), including dyspnea, peripheral edema, and ascites. Some patients have isolated diastolic dysfunction with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF > 40%-50%), most often as a consequence of hypertension or simply of aging. Half of patients with HF have impaired systolic dysfunction (LVEF < 40%) with associated increased filling pressures. Some patients have isolated right-sided HF, which typically presents predominantly with symptoms of peripheral congestion. These include pitting edema of extremities, hepatomegaly and congestion, ascites, and jugular venous distention. On the other hand, left-sided HF, which often progresses to biventricular failure, exhibits pulmonary symptoms before progressing to signs of peripheral volume overload. These include pulmonary edema, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, and cardiac asthma.

History and Physical Examination. Obtaining a thorough history and physical examination is critical in the evaluation of possible HF. A history should focus on exertional symptoms and triggers, alcohol and drug use, and recent viral infections. Physical exam should involve assessment for rales, displaced apical impulse, JVP, hepatojugular reflux, hepatomegaly, and extremity pitting edema. The presence of pulmonary edema more likely supports a diagnosis of left HF. Auscultatory findings may include an S4 (atrial gallop) or an S3 (ventricular gallop), low-pitched heart sound that is heard best with the bell of the stethoscope.

Diagnostic Workup. Workup should include an ECG, chest x-ray, TTE, and BNP levels. An ECG may reveal ventricular hypertrophy or previous myocardial infarction. Chest x-ray may show signs of pulmonary congestion, cardiomegaly, and other lung pathology. An echocardiogram is useful for assessment of EF, wall motion abnormalities, valvular disease, and possible pericardial fluid collection. BNP levels can be used to support clinical suspicion for HF. BNP values > 400 pg/mL are relatively sensitive for HF. Other appropriate investigations may include cardiac stress testing or coronary angiography if there are signs of myocardial ischemia.

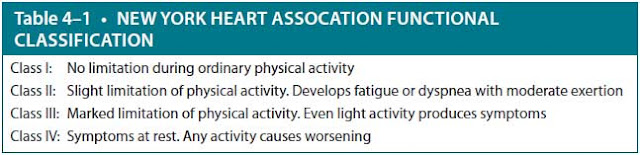

Staging. HF is a chronic and progressive syndrome that can be assessed by following the patient’s exercise tolerance, as done by the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification (Table 4–1). This functional classification carries prognostic significance. Individuals in class III who have low oxygen consumption during exercise have an annual mortality rate of 20%; in class IV, the rate is 60% annually. Patients with a low ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF < 20%) also have very high mortality risks. Death associated with HF may occur from the underlying disease process, cardiogenic shock, or sudden death as a result of ventricular arrhythmias.

Chronic Heart Failure Treatment

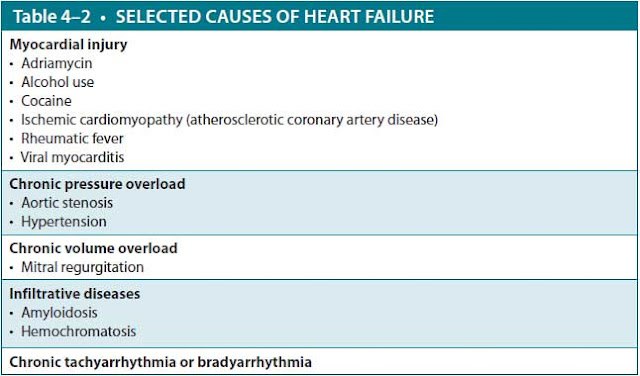

Although HF has many causes (Table 4–2), identification of the underlying treatable or reversible causes of disease is essential. For example, HF related to

tachycardia, alcohol consumption, or viral myocarditis may be reversible with removal of the inciting factor. In patients with underlying multivessel atherosclerotic coronary disease and a low EF, revascularization with coronary artery bypass grafting improves cardiac function and prolongs survival. The three major treatment goals for patients with chronic HF are relief of symptoms, prevention of disease progression, and a reduction in mortality risk.

Relief of Symptoms. The HF symptoms, which are mainly caused by low cardiac output and fluid overload, usually are relieved with lifestyle modifications and diuretics. Lifestyle changes may include reducing sodium intake to < 3 g daily, fluid restriction, establishing an exercise regimen, smoking cessation, and reduction of alcohol intake.

Preventing Disease Progression. Because HF has such a substantial mortality, measures to halt or reverse disease progression are necessary. Reversible causes should be aggressively sought and treated.

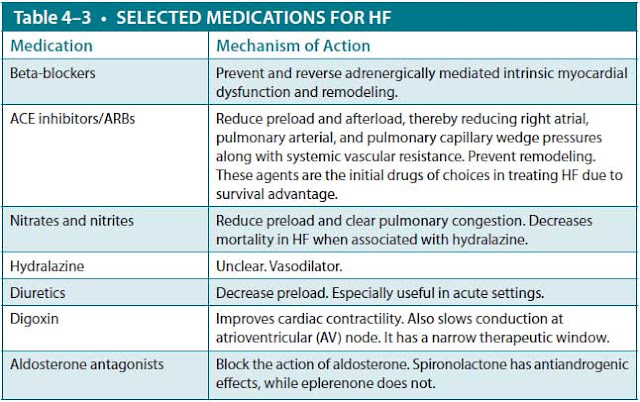

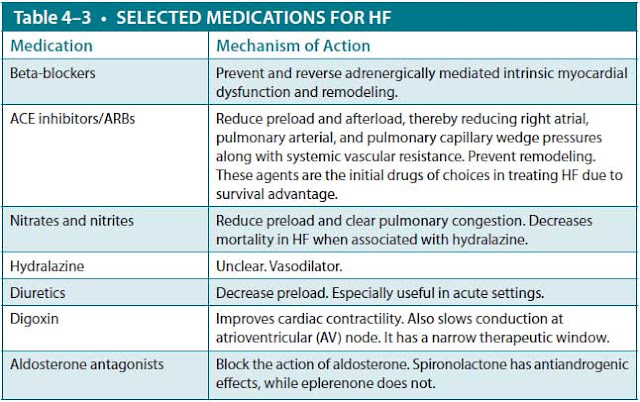

Decreasing Mortality Risk. Use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and some beta-blockers, such as carvedilol (CAR), metoprolol, or bisoprolol, have been shown to reduce mortality in patients with impaired systolic function and moderate-to-severe symptoms. In patients who cannot tolerate ACE inhibition (or in black patients in whom ACE inhibitors appear to confer less benefit), the use of hydralazine with nitrates has been shown to decrease mortality. Aldosterone antagonists such as spironolactone may be added to patients with NYHA class III or IV HF with persistent symptoms, but patients should be monitored for hyperkalemia. Digoxin can be added to these regimens for persistent symptoms, but it provides no survival benefit and can confer significant toxicity at supratherapeutic levels. The mechanisms of these various agents are outlined in Table 4–3. On the other hand, there are certain medications that are relatively contraindicated in HF; some examples include the nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (verapamil and diltiazem), which reduce

cardiac contractility, and the thiazolidinediones, a class of diabetes medications that can exacerbate HF.

Some devices may also be useful in reducing symptoms and mortality in patients with HF. Patients with depressed EF and advanced symptoms often have a widened QRS > 120 ms, indicating dyssynchronous ventricular contraction. Placement of a biventricular pacemaker, called cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), to stimulate both ventricles to contract simultaneously can improve symptoms and reduce mortality. Since patients with class II–III HF and depressed EF < 35% have elevated risk of sudden cardiac death due to ventricular arrhythmias, placement of an implanted cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) should be considered.

Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Treatment

In patients with acute decompensated HF, the initial treatment goals are to stabilize the patient’s hemodynamic derangements and to identify and treat reversible factors that may have precipitated the decompensation, such as arrhythmias or myocardial ischemia. Symptomatic treatment may include the use of oxygen, nitrates, and furosemide.

Regarding hemodynamics, if patients appear to have elevated LV filling pressures, they often require intravenous vasodilators such as nitroglycerin infusion, and patients with decreased cardiac output may require inotropes such as dobutamine; hypotensive patients may require vasoconstrictors such as dopamine.

Another complication that may arise is cardiorenal syndrome, a process that results from reductions in glomerular filtration rate due to renal hypoperfusion and renal venous congestion. Management includes treatment of the underlying HF and acute kidney injury.

CLINICAL APPROACH TO AORTIC STENOSIS

Pathophysiology

The history and physical findings presented in the scenario suggest that this patient’s HF may be a result of aortic stenosis. This is the most common symptomatic valvular abnormality in adults. Most cases occur in men. The causes of the valvular stenosis vary depending on the typical age of presentation: Stenosis in patients younger than 30 years usually is caused by a congenital bicuspid valve; in patients 30 to 70 years old, it usually is caused by congenital stenosis or acquired rheumatic heart disease; and in patients older than 70 years, it usually is caused by degenerative calcific stenosis.

Clinical Presentation

Typical physical findings of critical aortic stenosis include a narrow pulse pressure, a soft S2, a harsh late-peaking systolic murmur heard best at the right second intercostal space with radiation to the carotid arteries, and a delayed, slow-rising carotid upstroke (pulsus parvus et tardus). The ECG often shows LV hypertrophy. Doppler echocardiography reveals a thickened abnormal valve and can estimate aortic valve area and the transvalvular pressure gradient to determine severity. As the valve orifice narrows, the pressure gradient increases in an attempt to maintain cardiac output. Severe aortic stenosis is defined as a calcified valve with decreased systolic opening, an aortic velocity > 4 m/s, and a mean pressure gradient > 40 mg Hg; valve areas are typically less than 1 cm2(normal 3–4 cm2).

Symptoms of aortic stenosis develop as a consequence of LV hypertrophy as well as diminished cardiac output from flow-limiting valvular stenosis. The first symptom typically is angina pectoris, that is, retrosternal chest pain precipitated by exercise and relieved by rest. As the stenosis worsens and cardiac output falls, patients may experience syncopal episodes, typically precipitated by exertion. Finally, because of the low cardiac output and high diastolic filling pressures, patients develop clinically apparent HF as described previously. The prognosis for patients worsens as symptoms develop. The mean survival with angina, syncope, or HF is 5 years, 3 years, and 2 years, respectively.

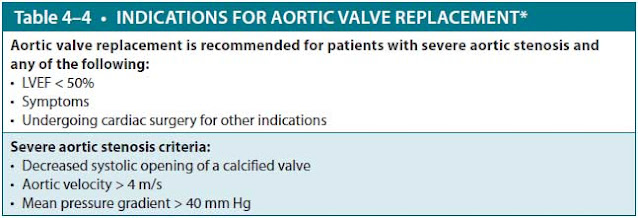

Treatment

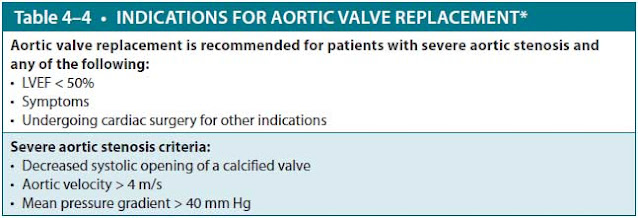

Patients with severe stenosis who are symptomatic or have a LVEF < 50% should be considered for aortic valve replacement (AVR). Indications for AVR are outlined in Table 4–4. Preoperative cardiac catheterization is routinely performed to provide definitive assessment of the aortic valve area and the pressure gradient, as well as to assess the coronary arteries for significant stenosis. There are three primary approaches to AVR: surgery, transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), and catheter balloon valvuloplasty. In patients who are not good candidates for valve replacement, the stenotic valve can be enlarged using balloon valvuloplasty, but this will provide only temporary relief of symptoms, as there is a high rate of restenosis. TAVR is a new technique that has been developed for patients who have an unacceptably high surgical risk, and catheter-based aortic valves have now been approved for use in both Europe and the United States.

*Data from Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 63(22): e57-e185.

Because the most common cause of HF is ischemic cardiomyopathy, the importance of preventive measures to reduce the likelihood of progressive cardiac dysfunction cannot be overstated. Primary prevention includes modification of risk factors: hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, poor dietary habits, physical activity, alcohol intake, and smoking. Maintaining an effective regimen for hypertension is critical to prevention of diastolic dysfunction, as uncontrolled hypertension can progress to concentric hypertrophy and diastolic failure. Elevated low-density lipoprotein levels > 190 mg/dL or a 10-year atherosclerotic coronary vascular disease (ASCVD) risk of > 7.5% should prompt the initiation of high-intensity statin therapy. Patients with diabetes should be on a regimen that aims to maintain a hemoglobin A1C between 7% and 8% while balancing the risk of hypoglycemia. Dietary changes should include reduction of salt intake and red meats with an increase in vegetables and whole grains. Adherence to an exercise regimen that includes 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity weekly is recommended. Reduction of alcohol intake and smoking cessation are also beneficial risk management strategies.

CASE CORRELATION

- See also Case 3 (Acute Coronary Syndrome) and Case 6 (Hypertension, Outpatient)

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

4.1 A 55-year-old man is noted to have moderately severe HF with impaired systolic function. Which of the following drugs would most likely lower his risk of mortality?

A. ACE inhibitors

B. Loop diuretics

C. Digoxin

D. Aspirin

4.2 In the United States, which of the following is most likely to have caused the HF in the patient described in Question 4.1?

A. Diabetes

B. Atherosclerosis

C. Alcohol

D. Rheumatic heart disease

4.3 A 75-year-old man is noted to have chest pain with exertion and has been passing out recently. On examination, he is noted to have a harsh systolic murmur. Which of the following is the best therapy for his condition?

A. Coronary artery bypass

B. Angioplasty

C. Valve replacement

D. Carotid endarterectomy

4.4 A 55-year-old man is noted to have HF and states that he is comfortable at rest but becomes dyspneic when he walks to the bathroom. On echocardiography, he is noted to have an EF of 50%. Which of the following is the most accurate description of this patient’s condition?

A. Diastolic dysfunction (HF with preserved EF)

B. Systolic dysfunction (HF with reduced EF)

C. Dilated cardiomyopathy

D. Pericardial disease

ANSWERS

4.1 A. ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers decrease the risk of mortality for patients who have HF with impaired systolic function. For this reason, these agents are the initial therapies of choice to treat HF. They both prevent and can even, in some circumstances, reverse cardiac remodeling.

4.2 B. In the United States, the most common cause of HF associated with impaired systolic function is ischemic cardiomyopathy due to coronary atherosclerosis.

4.3 C. The symptoms of aortic stenosis classically progress through angina, syncope, and, finally, HF, which has the worst prognosis for survival. This patient’s systolic murmur is consistent with aortic stenosis. An evaluation should include echocardiography to confirm the diagnosis and then AVR. The patient meets criteria for valve replacement because he is exhibiting symptoms.

4.4 A. When the EF is 50%, there is likely diastolic dysfunction with stiff ventricles. The stiff, thickened ventricles do not accept blood very readily. This patient has symptoms with mild exertion that are indicative of functional class III. The worst class is level IV, manifested as symptoms at rest or with minimal exertion. ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and beta-blockers are important agents in patients with diastolic dysfunction. The current nomenclature uses the terms preserved and reduced EF to replace diastolic and systolic HF, respectively.

CLINICAL PEARLS

▶ Heart failure is a clinical syndrome that is always caused by some under-lying heart disease, most commonly ischemic cardiomyopathy as a result of atherosclerotic coronary disease, or hypertension.

▶ HF can be caused by impaired systolic function (EF < 40%) or impaired diastolic function (with preserved systolic function).

▶ Chronic HF is a progressive disease with a high mortality. A patient’s functional class (exercise tolerance) is the best predictor of mortality and often guides therapy.

▶ The primary goals of therapy are to relieve congestive symptoms with salt restriction, diuretics, and vasodilators.

▶ ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, and aldosterone antagonists can decrease mortality in patients with HF.

▶ Cardiac resynchronization therapy and placement of an ICD can reduce symptoms and improve mortality in patients with advanced HF and low EF < 35%.

▶ Aortic stenosis produces progressive symptoms such as angina, exer-tional syncope, and HF, with increasingly higher risk of mortality. Valve replacement should be considered for patients with severe aortic steno-sis who exhibit symptoms or have an LVEF < 50%.

REFERENCES

Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(6):776-803.

Carabello BA. Clinical practice: aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:677-682.

Go A. On behalf of the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 127(2013):e6-e245.

Jessup M, Brozena S. Heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2007-2018.

Lejemtel TH, Sonnenblick EH, Frishman WH. Diagnosis and management of heart failure. In: Fuster V, Alexander RX, O’Rourke RA, eds. Hurst’s the Heart. 10th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2001:6.

Mann DL. Heart failure and cor pulmonale. In: Jameson JL, Fauci AS, Kasper D, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 20th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2018:1998-2015.

Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(22):e57-e185.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.