Acute Compartment Syndrome Case File

Eugene C. Toy, MD, Andrew J. Rosenbaum, MD, Timothy T. Roberts, MD, Joshua S. Dines, MD

CASE 13

A 55-year-old man with a history of atrial fibrillation develops a sudden sharp pain in his right leg. He presents to the emergency department, where he is found to have a cold right foot and calf, as well as nonpalpable pulses below the knee. The patient is taken to the operating room approximately 8 hours after the onset of the pain. He undergoes an embolectomy of a popliteal artery clot without complication. In the recovery room, however, he begins complaining of intense right foot and calf pain that continues to escalate, despite copious analgesia. When you evaluate the patient, he complains of 10/10 pain in his foot and calf that is constant, sharp, and without relief. On physical exam, his right lower leg is pale in comparison with the left and firm to touch. Palpable posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis pulses are present bilaterally. He experiences excruciating pain with passive dorsiflexion flexion of the right foot.

► What is the most likely diagnosis?

► How do you confirm the diagnosis?

► What is the appropriate treatment?

► What are the major complications associated with this condition?

ANSWER TO CASE 13:

Acute Compartment Syndrome

Summary: A 55-year-old man who initially presents with 8 hours of acute lower extremity ischemia develops sharp, constant pain after undergoing successful embolectomy. The patient has a pale, firm, painful leg and foot with palpable pulses.

- Most likely diagnosis: Acute compartment syndrome.

- How to confirm the diagnosis: Measure compartment pressures in the leg.

- Appropriate treatment: Emergency surgical fasciotomies to relieve elevated leg compartment pressures.

- Major complications: Rhabdomyolysis and myoglobinemia can cause renal failure. Additionally, if ischemia is prolonged, it can lead to significant tissue damage causing diminished limb function, muscle contractures, and possible limb loss.

- Understand the pathophysiology underlying compartment syndrome as well as the clinical signs and symptoms of the condition.

- Describe the diagnostic and therapeutic approach to compartment syndrome.

- Understand the complications caused by the direct effects of elevated compartment pressures, as well as complications from myoglobinemia.

Considerations

The patient’s history of prolonged lower extremity ischemia should raise the concern for the development of a compartment syndrome. Although most frequently associated with trauma, a number of nontraumatic injuries can also lead to the development of a compartment syndrome, such as reperfusion or rhabdomyolysis. This patient had an acute thrombosis of his popliteal artery with subsequent ischemia to his lower leg and foot for 8 hours. Many advocate performing prophylactic fasciotomies in any patient whose ischemia time, from an injury such as this one, exceeds 4 to 6 hours. Although the patient does not present with all of the classic “5 Ps” (see “Definitions” in the next section) it is rare to see a patient who in fact has all 5 signs and symptoms. The presence of all “5 Ps” typically represents a severe and advanced stage of compartment syndrome. The presence of palpable pulses should not impede your diagnosis of a compartment syndrome if other clinical findings suggest the diagnosis. Loss of pulses is typically the last sign and requires a significant intra-compartment pressure. Waiting for the patient to lose pulses will result in a more extensive injury to the compartmental muscle and nerves as well as increasing the risk for and severity of renal damage.

APPROACH TO:

Compartment Syndrome

DEFINITIONS

COMPARTMENT SYNDROME: A clinically diagnosed condition of increased intra-compartmental pressure within a closed space, causing reduced tissue perfusion and subsequent tissue necrosis.

5 Ps: Five signs and symptoms classically found in patients with compartment syndrome, including: pain out of proportion to exam, paralysis, paresthesias, pallor, pulselessness. Sometimes poikilocytosis (coolness) is considered a sixth “P”.

RHABDOMYOLYSIS: Breakdown of muscle that leads to intravascular leakage of electrolytes and proteins, including myoglobin.

CLINICAL APPROACH

Compartment syndrome results from an increase in tissue pressure within a confined fascial space that limits any expansion of the compartment’s volume to compensate for the increase in pressure. As the pressure rises, the compartment’s pressure eventually exceeds the capillary perfusion pressure, causing impaired oxygen delivery to tissue and subsequent tissue damage. Irreversible cellular damage, which results in breakdown of the intracellular organelles and cellular membranes, leads to leakage of intracellular electrolytes, including phosphorous, potassium, and myoglobin, as well as the activation of inflammatory cascades. This results in further swelling and tissue edema that, in turn, results in even further compartment pressure elevation. Rhabdomyolysis, the rapid breakdown of damaged muscle, may lead renal failure and dangerous electrolyte imbalances such as hyperkalemia and hypocalcemia. Hyperkalemia relates directly to intracellular potassium leakage; hypocalcemia indirectly results from the release of phosphate ions that bind and sequester available calcium.

Although compartment syndrome exists in both acute and chronic forms, it is typically thought of as an acute process. For the purpose of this discussion, acute and chronic forms of this syndrome are discussed separately.

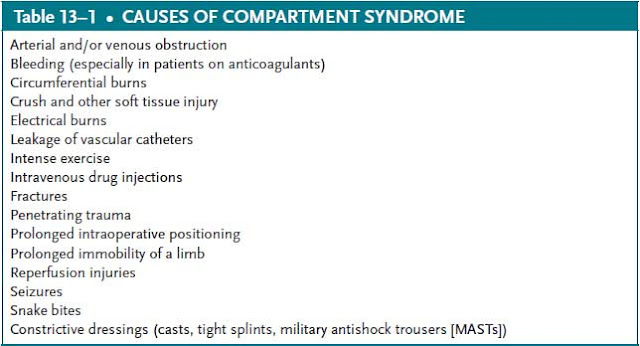

Acute Compartment Syndrome

Although compartment syndrome is frequently associated with closed fractures, particularly comminuted fractures of the upper or lower extremities, it can be caused by any process that leads to impaired tissue perfusion. Additional causes of compartment syndrome include external compression such as constrictive casting, hematomas, arterial or venous thrombosis, intravenous (IV) infiltration, and leakage of fluid into the interstitial space ( Table 13–1 ). Although not common, improper positioning for surgical procedures (especially prolonged positioning in lithotomy or Trendelenburg positions) can lead to impaired venous return and subsequent compartment syndrome.

The most common fractures associated with the development of compartment syndrome are closed tibial fractures, followed by forearm fractures. Some series report the incidence of compartment syndrome after closed tibia fractures to be approximately 20%. Physicians must be highly suspicious of compartment syndrome in the patient who develops increasing pain following closed reduction and immobilization. Significant pain with passive stretching of the toes (or fingers, in a forearm injury) should warrant removal of the cast or splint and careful reassessment for compartment syndrome.

Compartment syndrome is a clinical diagnosis based on signs and symptoms in the appropriate clinical setting. Although the syndrome is classically described by the “5 Ps”, it is rare to find a patient who has all 5 (or 6 if you include coolness) of these signs and symptoms. None of the “5 Ps” are pathognomonic for this condition, and therefore diagnosis of compartment syndrome is primarily a clinical diagnosis. For example, pain, which typically represents the first clinical complaint, is extremely nonspecific. Pulselessness, which is a late finding and does not occur until the compartment pressures are significantly elevated, may be a baseline finding in patients with peripheral vascular disease. An additional physical exam finding that is frequently seen with compartment syndrome is pain on passive movement of the muscles within the effected compartment.

Confirmation of the diagnosis is made by directly measuring the compartment pressures using either a side-port needle or a slit catheter ( Figure 13–1 ). Compartment pressures within 30 mmHg of the patient’s diastolic blood pressure warrant emergency operative intervention. Although compartment pressure measurements are extremely useful in confirming the diagnosis of compartment syndrome, it is primarily a clinical diagnosis, and therefore measurement of compartment pressures should not delay surgical intervention if the clinical picture is clear. Additionally, many advocate for prophylactic intervention with fasciotomies to prevent the development of a compartment syndrome if there has been greater than 4 to 6 hours of limb ischemia.

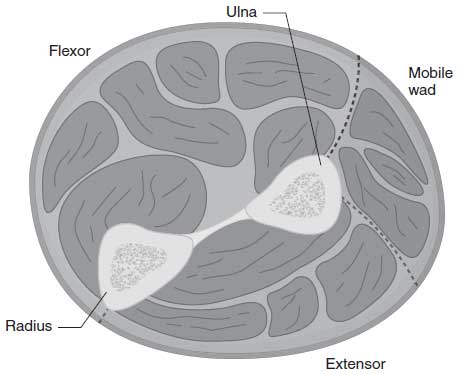

Surgical intervention is performed via an operative fasciotomies. Depending on the extent of injury and tissue edema, the overlying skin can either be closed at the time of surgery or can be closed once the edema has decreased. This will sometimes require the use of skin grafts at a later date. In most cases, the fasciotomies are performed through 2 skin incisions that are positioned so that all fascial compartments can be decompressed. In the leg, fasciotomies involve releasing the anterior, lateral, superficial, posterior, and deep posterior compartments ( Figure 13–2 ). Fasciotomies of the thigh involve release of the medial, anterior, and posterior compartments. In the arm, proximal fasciotomies involve releasing the anterior and posterior compartments, whereas forearm fasciotomies require opening the dorsal and volar compartments with extension into the carpal tunnel and mobile wad compartment located on the radial aspect of the forearm ( Figure 13–3 ). Fasciotomies are generally not performed after 48 hours unless there is remaining function documented within the muscles of that compartment. Amputation may be necessary in these settings.

Figure 13–1. A slit catheter device used to measure compartment syndrome. (Reproduced, with

permission, from Tintinalli J, et al. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2010:Fig. 275-6.)

When performing fasciotomies, it is important to ensure that the fascial openings are long enough to fully decompress the muscle within. If the underlying injury is severe and the openings are inadequate, compartment syndrome can recur. Failure to appreciate this fact can easily lead to further tissue damage and subsequent complications.

The cellular damage that occurs from prolonged compartment syndrome leads to release of potassium, phosphorous, and myoglobin. Evaluation of the degree of muscle damage and breakdown can be followed with serial measurements of creatine phosphokinase (CPK), which serves as an indirect gauge of the degree of myoglobinemia. Myoglobin, the oxygen storing molecule of muscles, can crystallize within the renal tubules and lead to significant renal injury. Management of this severe myoglobulinemia primarily involves aggressive hydration with IV fluids with a goal of maintaining urine output of approximately 100 mL/hr or >1 mL/kg/hr. Some advocate for IV fluid supplementation with sodium bicarbonate with the goal of increasing the pH of urine and increasing the solubility of myoglobin to reduce crystallization and subsequent renal damage.

Figure 13–2. The 4 compartments of the leg. (Reproduced, with permission, from Tintinalli J, et al.

Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2010:Fig. 275-1.)

Figure 13–3. The forearm compartments. (Reproduced, with permission, from Tintinalli J, et al.

Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2010:Fig. 275-2.)

Patients with rhabdomyolysis also require continuous cardiac monitoring, as the hypocalcemia and hyperkalemia associated with muscle breakdown can lead to cardiac arrhythmias. Depending on the degree of hyperkalemia, patients may require further medical interventions, including calcium chloride or calcium gluconate for myocardial protection as well as insulin/glucose, sodium bicarbonate, and polystyrene sulfonate, a potassium binder.

Outcomes after the development of acute compartment syndrome are largely determined by the severity of the inciting injury, the timing of diagnosis, and the extent and severity of tissue damage. Although the majority of patients who sustain renal injury from rhabdomyolysis will eventually have a full recovery of renal function, rhabdomyolysis complicated by acute kidney injury is associated with a mortality rate as high as 20%. Furthermore, requirement for intensive care unit admission in the setting of rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury is associated with a mortality rate reaching nearly 60%.

Chronic Compartment Syndrome

Although compartment syndrome is most commonly seen and discussed as an acute process, it can also exist in a chronic form. The chronic form of compartment syndrome is an exercise-induced phenomenon that results in recurrent pain with activity and relief with rest. The chronic form of this syndrome is not typically associated with significant muscle necrosis nor renal damage. A diagnosis of chronic compartment syndrome is confirmed by measuring intra-compartment pressures before and after exercise. Treatment options include surgical fasciotomies for pain relief and increased exercise tolerance, prolonged periods of rest in conjunction with modifying the offending activity or exercise routine, and continuing with current exercise routines despite the pain and discomfort that they cause. Those who elect to defer surgical intervention or lifestyle modification should be made aware that

chronic compartment syndrome can on occasion develop into an acute compartment syndrome.

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

13.1 A 24-year-old man is noted to have a urinalysis that is positive for blood. The microscopic examination of the urine is negative for casts or red blood cells. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

13.2 A 55-year-old woman is noted to have a traumatic injury to her right thigh. Which of the following is most sensitive for the diagnosis of compartment syndrome?

13.3 A 22-year-old roofer is brought into the ED due to hyperthermia. The urinalysis is positive for blood, and the serum CPK is markedly elevated. The patient is noted to likely have compartment syndrome and rhabdomyolysis. What is the appropriate infusion rate for IV hydration for this patient?

A. 4 mL/kg/% body surface area affected

B. 4 mL/kg/hr for the first 10 kg + 2 mL/kg/hr for the next 10 kg + 1 mL/kg/hr for each subsequent kilogram

C. Titrated to urine output of 0.5 mL/kg/hr

D. Titrated to urine output of 1 mL/kg/hr

ANSWERS

13.1 D. A urinalysis that is positive for blood does not distinguish between myoglobin and hemoglobin. A microscopic urine exam is necessary for a definitive diagnosis. In a patient with myoglobinuria, a microscopic evaluation will fail to show the presence of red blood cell (RBC) casts or intact RBCs. Gross myoglobinuria can lead to an abnormal coloration of the urine and is typically described as “cola colored.” Hematuria and renal cell carcinoma would be expected to produce urinalysis and microscopic exam that are positive for RBCs, whereas nephritic syndrome would be expected to have RBC casts.

13.2 C. Pain, typically severe and even out of proportion to the injury, represents the first and most sensitive symptom of compartment syndrome. Pain, however, is extremely nonspecific. Pulselessness represents a very late finding, and therefore the finding of a palpable pulse should not exclude compartment syndrome in your differential diagnosis.

13.3 D. IV fluids should be titrated to maintain urine output greater than 1 mL/ kg/hr to minimize the risk of myoglobin precipitation within the renal tubules and minimize the extent of kidney injury. Choice A represents a modification of the Parkland formula used in burn management (4 mL/kg/body surface area of second- and third-degree burns). Choice B represents the calculation of maintenance IV fluid. Choice C represents the typical urine output goal for most patients.

CLINICAL PEARLS

► Compartment syndrome is a clinical diagnosis. Although measurement of compartment pressures can be used to confirm the diagnosis, treatment should not be delayed for compartment pressure measurements if the diagnosis is clear.

► Pulselessness is typically a late sign, and treatment should not be delayed until it is present.

► Incomplete and/or inadequate fasciotomies can result in a subsequent redevelopment of a compartment syndrome.

► Ischemia lasting greater than 4 to 6 hours typically requires prophylactic fasciotomies to prevent development of a compartment syndrome.

► Compartment pressures within 30 mmHg of the patient’s diastolic pressure are indicative of compartment syndrome and require emergency operative intervention.

|

REFERENCES

Bosch X, Poch E, Grau JM. Rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:62-72.

Frink M, Hildebrand F, Krettek C, Brand J, Hankemeier S. Compartment syndrome of the lower leg and

foot. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:940-950.

Huerta-Alardén AL, Varon J, Marik PE. Bench-to-bedside review: rhabdomyolysis—an overview for

clinicians. Crit Care. 2005;9:158-169.

Konstantakos EK, Dalstrom DJ, Nelles ME, Laughlin RT, Prayson MJ. Diagnosis and management of

extremity compartment syndromes: an orthopaedic perspective. Am Surg. 2007;73:1199-1209.

Shadgan B, Menon M, Sanders D, Berry G, Martin C Jr, Duffy P, Stephen D, O’Brien PJ. Current

thinking about acute compartment syndrome of the lower extremity. Can J Surg. 2010;53:

329-334.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.