Parkinson Disease Case File

Eugene C. Toy, MD, Ericka Simpson, MD, Pedro Mancias, MD, Erin E. Furr-Stimming, MD

CASE 4

A 55-year-old Caucasian man with a history of hypertension presents with complaints of tremor and impaired dexterity in his right hand and arm. Two years ago, he noticed a tremor in his right hand, which was more pronounced at rest and while walking. Though it was initially not bothersome, it has gradually progressed and he now finds it embarrassing while speaking to his colleagues at work. He describes a change in his handwriting, noting that it has gotten progressively smaller. More recently, he has developed difficulty walking and has occasional hesitation in his gait. He has also noticed tremulousness of his right foot, though to a lesser degree than in his hand. His wife reports that he sometimes acts out his dreams or “kicks” while sleeping, and she has noted this for several years prior to the onset of his tremors. Physical examination reveals a low-frequency (4-6 Hz), moderate amplitude tremor in his right hand and arm at rest, which is attenuated with movement and worsens with ambulation, or 5 seconds after holding out his arms. There is generalized slowness in purposeful movements of his hands and feet, more prominent on the right side. Tone is mildly increased in his right upper extremity (described as cogwheel rigidity) but is normal elsewhere. Facial expression is decreased, and his affect appears somewhat flat. He ambulates slowly and deliberately, with shortened stride length, stooped posture, and a decrease in arm swing on the right. He has difficulty with turns and is unable to pivot smoothly. The remainder of his physical examination is unremarkable.

▶ What is the most likely diagnosis?

▶ What is the next diagnostic step?

▶ What is the next step in therapy?

ANSWERS TO CASE 4:

Parkinson Disease

Summary: A 55-year-old man with hypertension presents with a 2-year history of unilateral resting tremor associated with slowness of movement and change in gait.

- Most likely diagnosis: Idiopathic Parkinson disease (PD).

- Next diagnostic step: If clinical history and examination are consistent with PD and no atypical features (see below) are present, no specific neuroimaging is required.

- Next step in therapy: Dopaminergic therapies may be considered, with drug selection based on patient’s age, symptom severity, side-effect profile, and preference. Mainstay dopaminergic medications include carbidopa/levodopa, dopamine agonists, monoamine oxidase type B (MAO-B) inhibitors, and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors.

- Describe the cardinal features of parkinsonism.

- Describe the difference between parkinsonism and PD.

- Provide a differential diagnosis for parkinsonism based on clinical features and risk factors.

- Describe the distinguishing clinical and histopathologic features of PD.

- Recognize the unique features of the neurodegenerative “Parkinson plus” syndrome, including multiple system atrophy (MSA), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), and diffuse Lewy body (DLB) disease.

- Describe current treatment options for PD.

Considerations

This 55-year-old man has a history of tremor and impaired right-hand motor precision, which is a common presentation of PD. The patient has had progressive tremor over the past 2 years. The micrographia (small handwriting) is also a common finding. He has noticed gait problems, with tremor and hesitation. The physical examination shows a low-frequency (4-6 Hz), moderate amplitude tremor in his right hand and arm at rest, which is attenuated with movement and worsens with ambulation, or 5 seconds after holding out his arms, which are also common features of PD. In its later stages, PD affects cognition leading to dementia. This patient has generalized slowness in purposeful movements of his hands and feet, more prominent on the right side. There is also mildly increased tone in his right upper extremity (described as cogwheel rigidity) but is normal elsewhere.

PD patients also have decreased facial expression, and his affect appears somewhat flat. He ambulates slowly and deliberately, with shortened stride length, stooped posture, and a decrease in arm swing on the right, which is described as a “shuffling gait.” He has difficulty with turns and is unable to pivot smoothly. This patient presents with many of the classic findings of PD. An evaluation should be

performed to assess for secondary causes of PD such as medications or cerebral conditions such as cerebrovascular accident (CVA). There is no single test to diagnose PD, but rather clinical evaluation is used to rule out other causes.

Parkinsonism has classically been defined with the clinical triad of bradykinesia, rigidity, and resting tremor, regardless of the etiology of these manifestations. Postural instability is sometimes included as a fourth cardinal feature. The most common cause of parkinsonism is idiopathic PD.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Causes of secondary parkinsonism, most commonly associated with drug exposure or stroke, should be considered in patients depending on their clinical history and examination. Moreover, atypical parkinsonian disorders other than PD should be considered.

Primary Parkinsonism

Idiopathic Parkinson disease (PD) is among the most common neurologic disorders, affecting 1% of individuals older than 60 years. As a distinct diagnostic entity, PD is associated with loss of pigmented dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra as well as intracytoplasmic inclusions of alpha-synuclein aggregates called Lewy bodies. Clinically, PD consists of both motor and nonmotor symptoms. Motor symptoms of PD include bradykinesia, rigidity, resting tremor, postural instability, and gait disturbance. Nonmotor symptoms include rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavioral disorder, hyposmia (inability to smell odors), autonomic dysfunction such as constipation, urinary frequency, and orthostatic hypotension and psychiatric disorders including depression and anxiety.

Secondary Parkinsonism

Vascular parkinsonism resulting from subcortical infarcts affecting the extrapyramidal motor system should be considered in patients with cardiovascular risk factors, including history of stroke or coronary artery disease. In general, vascular parkinsonism is more commonly associated with “negative”—inhibited movement—parkinsonian features (bradykinesia, rigidity) than with tremor.

Drug-induced parkinsonism is usually caused by dopamine blocking agents, including antipsychotics and antiemetics such as metoclopramide. Contamination of synthetic opioids with chemicals such as 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3, 6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) was implicated in the development of parkinsonian features in intravenous drug users in the 1970s.

Parkinson Plus Syndromes

Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is a multifocal neurodegenerative condition that is often associated with parkinsonism or cerebellar features and prominent autonomic insufficiency. Two variants exist: MSA-P, the parkinsonian form, previously called striatonigral degeneration, with symmetric features that distinguish it from PD, and MSA-C, previously termed olivopontocerebellar atrophy, which presents as a predominantly cerebellar syndrome. Both may have prominent and early autonomic insufficiency, including orthostatic hypotension, constipation, urinary frequency, and impotence.

Diffuse Lewy body (DLB) disease, also called Lewy body dementia, is a neurodegenerative dementia syndrome which frequently is associated with parkinsonism. In addition to cognitive dysfunction, key features include parkinsonism, clinical fluctuation, visual hallucinations, and marked sensitivity to neuroleptics. As psychiatric symptoms are common and may be the predominant manifestation of disease, psychopharmacotherapy may be required. The atypical antipsychotics quetiapine and clozapine are preferred, as they are less likely to worsen symptoms. In addition to DLBs (intracytoplasmic alpha-synuclein inclusions), there is significant loss of cholinergic neurons, similar to Alzheimer disease. Accordingly, recommended first-line pharmacotherapy is with cholinesterase inhibitors. Unfortunately, the parkinsonian symptoms in DLB are generally less responsive to l-dopa therapy, and dopaminergic medications may worsen cognitive or psychiatric symptoms.

Corticobasal degeneration (CBD) is a neurodegenerative disorder associated with parkinsonism and prominent apraxia. The hallmark finding described is the alien limb phenomenon, in which a patient may feel that the limb has “a mind of its own,” controlling its own movement. Similar to PD, CBD is predominantly unilateral.

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a neurodegenerative condition, which commonly presents with parkinsonism and impaired voluntary vertical gaze (supranuclear ophthalmoplegia). Impaired downward gaze is the most specific historical finding. Interestingly, vertical oculocephalic or doll’s eye testing remains intact, as brainstem (infranuclear) pathways are unaffected. Gaze limitations lead to frequent falls, which is often the sentinel symptom.

Essential Tremor

See Case 1.

CLINICAL APPROACH

In 1817, James Parkinson enumerated the hallmark features of the disease “paralysis agitans” in An Essay on the Shaking Palsy. Jean-Martin Charcot later proposed that the disease be renamed to honor Parkinson’s contributions. Features of PD can be expressed in other ways, including difficulty rising from a chair, difficulty turning in bed, micrographia, masked face, stooped, shuffling gait with decreased arm swing, and sialorrhea (excess drooling). Although PD is thought of as a motor disorder, sensory systems are also affected. Loss of sense of smell occurs in 80% to 100% of patients. Patients also frequently develop constipation, which can present before or after the diagnosis of PD is made.

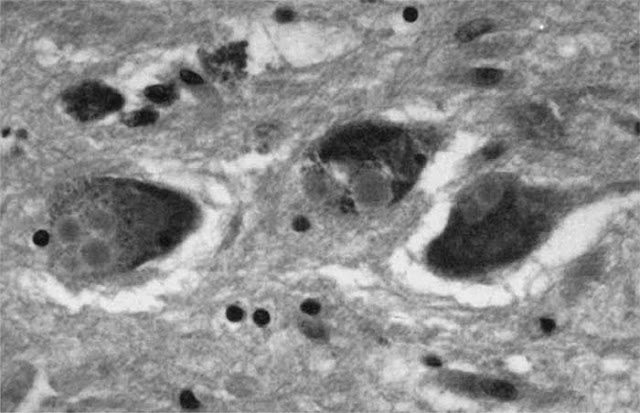

Figure 4–1. Lewy bodies on microscopy. (Reproduced, with permission, from Watts RL, Koller WC. Movement Disorders: Neurologic Principles and Practice. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2004:146.)

The classic pathologic feature of PD is loss of pigmented cells in the substantia nigra. The remaining neurons may show intracytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusions called Lewy bodies (Figure 4–1). PD is associated with marked striatal dopamine (DA) depletion and is considered by many to be a striatal dopamine deficiency syndrome. At death, DA loss is greater than 90%, while a loss of approximately 70% striatal DA is required to develop symptoms. Severity of DA loss best correlates with bradykinesia in PD; correlation with tremor is poor.

Clinically, patients can present with both motor and nonmotor symptoms. The Movement Disorders Society has proposed clinical criteria that incorporate the cardinal motor symptoms of bradykinesia, resting tremor, and rigidity as essential criteria along with supportive criteria, such as clear and dramatic beneficial response to dopaminergic therapy; presence of levodopa-induced dyskinesias; rest tremor of a limb; and/or presence of either olfactory loss or cardiac sympathetic denervation. “Red flag” or atypical features for PD include the following:

- Early onset of, or rapidly progressing, dementia

- Rapidly progressive course

- Supranuclear gaze palsy

- Upper motor neuron signs

- Cerebellar signs—such as dysmetria or ataxia

- Urinary incontinence

- Early symptomatic postural hypotension (within 5 years of the disease)

- Early falls

Inherited forms of PD have been described but they constitute only a small percentage of PD patients. Approximately 90% of patients with PD do not have a family history and are considered to be sporadic. Familial PD, while rare, does occur and is most commonly associated with early- or young-onset PD, for which multiple genes have been implicated. Routine neuroimaging is usually unremarkable in PD. Functional imaging designed to visualize the dopamine stores in the striatum using I-123 single-photon emission tomography (DaTscan) may provide better diagnostic predictive value in the future. While a DaTscan may help differentiate patients with primary parkinsonian syndromes (idiopathic PD, Parkinson plus syndromes) from differentials such as essential tremors or normal controls, it cannot differentiate reliably within the primary parkinsonian syndrome subtypes.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Treatment is initiated when the patient’s quality of life is negatively affected and usually consists of carbidopa/levodopa, a dopamine agonist and/or an MAO-B inhibitor. There is currently no FDA-approved treatment for disease modification; therefore, symptomatic treatment is the mainstay of therapy. This includes pharmacologic and surgical interventions. Physical measures such as physical therapy, speech therapy, and exercise are important, and they have a major impact on the lives of patients with PD.

Pharmacologic Therapy

- Dopaminergic agents are the mainstay of treatment for the cardinal features of PD.Levodopa crosses the blood–brain barrier, while dopamine does not; levodopa is converted to dopamine in the brain. Peripheral breakdown in the gut is inhibited by the addition of aromatic amino acid decarboxylase inhibitors (carbidopa). Thus, a carbidopa/levodopa formulation is generally preferred. Levodopa can also be broken down peripherally by the enzyme COMT so that COMT inhibitors such as entacapone and tolcapone are used. Treatment paradigms generally favor L-dopa–sparing therapies for initial treatment, unless symptoms are severe at the time of diagnosis.

- Dopamine agonists cross the blood–brain barrier and act directly at predominantly D2-type receptors without requiring conversion. These agents include pramipexole, ropinirole, and rotigotine. Compared to other therapies, dopamine agonists are more likely to cause problems with impulsivity, including gambling, shopping, or hypersexual tendencies.

- MAO-B inhibitors such as selegiline and rasagiline can improve symptoms in both patients with mild disease (as monotherapy) and patients already on levodopa therapy. Many clinicians prefer monotherapy with MAO-B inhibitors for early, mild PD. MAO inhibitors have previously been implicated with development of serotonin syndrome and should be used cautiously when combined with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

- Amantadine is felt to act primarily by blocking glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and has a mild attenuation of the cardinal symptoms of resting tremor and dystonia. Amantadine has also been shown to help alleviate levodopa-induced dyskinesias.

Although no treatment definitively slows the progression of PD, mortality has been reduced and quality of life has been improved by levodopa therapy. Over time, the response to levodopa becomes unstable, resulting in “on-off” fluctuations. Also, patients can develop troublesome abnormal involuntary choreiform and dystonic movements called dyskinesias. Younger patients are more at risk for dyskinesia and are likely to be treated for long periods of time. Surgical treatment with the placement of deep brain stimulators (DBSs) may be considered in patients with significant motor fluctuations and dyskinesias despite medication adjustment. DBS involves placement of stimulating electrodes into the subthalamic nucleus (STN) or globus pallidus interna (GPi) bilaterally. Comorbid or prior history of dementia is an exclusion criterion for DBS placement, as worsening of cognitive function after DBS implantation has been reported.

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

4.1 A 55-year-old woman presents with a 5-year history of gradual loss of function. The patient’s daughter has been researching on the Internet and suspects PD. Which of the following signs is most suggestive of PD rather than the other neurodegenerative diseases?

A. Unilateral resting tremor

B. Supranuclear downward gaze palsy

C. Orthostatic hypotension early in the course of the disease

D. Early falls

E. Abnormal cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

4.2 A 61-year-old man is diagnosed with mild PD. In discussion about therapy, you review the medication rationale and also the side effects associated with the medications. Which of the following medications is most likely to be able to help relieve his mild symptoms of PD without increasing risk of dyskinesias?

A. Levodopa

B. Dopamine agonists

C. Amantadine

D. Anticholinergics

E. Haloperidol

4.3 A 35-year-old man is being evaluated for resting tremor, rigidity, and difficulty with balance. In reviewing the medications, you suspect drug-induced parkinsonism. Which of the following medications would be most likely to be responsible?

A. Trihexyphenidyl

B. Metoclopramide

C. Diazepam

D. Carbidopa

E. Levodopa

ANSWERS

4.1 A. Resting tremor is an early manifestation of PD. The other answer choices are more atypical of PD and may indicate other neurologic disorders.

4.2 C. Amantadine can decrease the incidence of levodopa-induced dyskinesia. It acts by blocking glutamate NMDA receptors and has a mild attenuation of the cardinal symptoms of resting tremor and dystonia.

4.3 B. Antiemetic agents such as prochlorperazine (Compazine) and metoclopramide can cause a drug-induced parkinsonism. The three classes of drugs most likely to cause drug-induced PD are dopamine receptor blocking agents (prochlorperazine and metoclopramide), dopamine depleting agents (reserpine, tetrabenazine), and atypical antipsychotic agents. Although there are some subtle differences between drug-induced PD and PD, it is often difficult to differentiate between the two.

CLINICAL PEARLS

|

▶ The cardinal features of parkinsonism

are resting tremor, rigidity,

bradykinesia, and postural

instability.

▶ Patients with idiopathic PD should

have a unilateral onset of motor

symptoms such as tremor, rigidity,

and bradykinesia.

▶ Postural instability leading to falls

occurs relatively late in the clinical course of PD.

▶ Failure to respond clinically to

large doses of levodopa may suggest a diagnosis other than idiopathic PD.

▶ The mainstay of therapy for PD is

carbidopa/levodopa that, after long-term use, can lead to motor

fluctuations and dyskinesias.

▶ MAO-B inhibitors or dopamine agonists

can be considered as first-line monotherapy in patients younger than 75 years

with early or mild PD.

|

REFERENCES

Hess C, Okun M. Diagnosing Parkinson disease. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2016;22(4):1047-1063.

Horstink M, Tolosa E, Bonuccelli U, et al. European Federation of Neurological Societies; Movement Disorder Society—European Section. Review of the therapeutic management of Parkinson’s

disease. Report of a joint task force of the European Federation of Neurological Societies and the Movement Disorder Society—European Section. Part I: early (uncomplicated) Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:1170-1185.

Kägi G, Bhatia KP, Tolosa E. The role of DAT-SPECT in movement disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:5-12.

de Lau LM, Breteler MM. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:525-535.

Martin I, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Recent advances in the genetics of Parkinson’s disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2011;12:301-325.

Olanow CW, Rascol O, Hauser R, et al. A double-blind, delayed-start trial of rasagiline in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(13):1268-1278.

Pahwa R, Factor SA, Lyons KE, et al. Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter: treatment of PD with motor fluctuations and dyskinesia (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology.

Neurology. 2006;66:983-995.

Postuma RB, Berg D, Stern M, et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30(12):1591-1601.

Tolosa E, Wenning G, Poewe W. The diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:75-86.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.