Chronic Diarrhea Case File

Eugene C. Toy, MD, Gabriel M. Aisenberg, MD

Case 23

A 38-year-old man without a significant medical history presents for an evaluation. He reports a 9- to 12-month history of intermittent diarrhea associated with mild cramping. He reports that his stools are usually large volume, nonbloody, and greasy. He has unintentionally lost more than 20 lb during this period but says that his appetite and oral intake have been good. He has tried taking a proton pump inhibitor daily for the last several months, but it has not improved his symptoms. He also tried refraining from any intake of dairy products, but that did not affect the diarrhea either. He has not experienced fever or any other constitutional symptoms. He does not smoke and drinks an occasional beer on the weekends, but not regularly. He is married, is monogamous, and does not know his family medical history due to being adopted.

On examination, he is afebrile, normotensive, and comfortable appearing. He has some glossitis but no oral lesions. His chest is clear to auscultation, and his heart is regular in rate and rhythm. On abdominal examination, his bowel sounds are active; no tenderness, masses, or organomegaly are evident on palpation. Rectal examination is negative for occult blood. He has some patches of papulovesicular lesions on his elbows, knees, and abdomen with some excoriations; he says it is very itchy.

▶ What is the most likely diagnosis?

▶ What is the next step in management?

▶ What is the best diagnostic test?

▶ What are the risk factors for this condition?

▶ What is the best treatment?

ANSWERS TO CASE 23:

Chronic Diarrhea

Summary: A 38-year-old man presents with

- Chronic diarrhea

- Nonbloody, greasy stools suggestive of fat malabsorption

- Unintentional weight loss without systemic symptoms

- Glossitis suggestive of vitamin deficiency

- Rash on extensor surfaces consistent with dermatitis herpetiformis (papules and blisters that are very itchy)

Most likely diagnosis: Chronic diarrhea due to celiac disease.

Next step in management: Check serum tissue transglutaminase (tTG)–Ig (immunoglobulin) A and endomysial (EMA)–IgA antibody.

Best diagnostic test: Endoscopic examination with small-bowel biopsy.

Risk Factors: Family history of celiac disease, autoimmune conditions (type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroiditis), Down syndrome, Turner syndrome.

Best treatment: Adherence to a gluten-free diet to improve small-intestine mucosal morphology.

- Describe the initial evaluation and management of acute infectious diarrhea. (EPA 1, 3, 4)

- List the indications for antibiotic treatment of acute diarrhea. (EPA 4)

- Recognize the pathophysiology of chronic diarrhea. (EPA 2, 12)

- Understand the diagnosis, management, and complications of celiac disease. (EPA 1, 4, 10)

Considerations

This patient has chronic diarrhea with worrisome features such as weight loss and nutritional deficiency secondary to malabsorption. It is important to distinguish between functional causes of chronic diarrhea, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and more significant causes of diarrhea, such as inflammatory diseases and malabsorption, that may lead to complications or adverse long-term sequelae. Some of the red flags that indicate a pathologic etiology include weight loss, fever, fatigue, bloody diarrhea, systemic symptoms such as joint pain, and nutritional deficiencies. Celiac disease, an autoimmune sensitivity to gluten, is an important diagnosis to consider because the clinical manifestations may be subtle. This patient’s rash, which is very suspicious for dermatitis herpetiformis (raised red papules that can erupt into blisters and is very pruritic), is strongly associated with celiac disease. Once a diagnosis is established, most patients can be managed with dietary modification to improve symptoms and prevent complications.

DEFINITIONS

ACUTE DIARRHEA: Diarrhea of duration less than 14 days.

CELIAC DISEASE: Small-bowel disorder characterized by symptoms of malabsorption and an abnormal small-bowel biopsy; it occurs with exposure to dietary gluten and improves after elimination of gluten from the diet.

CHRONIC DIARRHEA: Diarrhea of more than a 4 weeks’ duration; it is sometimes called persistent diarrhea.

DIARRHEA: Passage of abnormally liquid or unformed stool at increased frequency.

INFLAMMATORY DIARRHEA: Diarrhea that can be osmotic, secretory, or mixed in presentation and presents with systemic symptoms.

INVASIVE DIARRHEA: Diarrhea consisting of bloody stools or mucus; it is also called dysentery. This may occur with fever and abdominal pain.

OSMOTIC DIARRHEA: Diarrhea that occurs due to water drawn into the gut lumen by a poorly absorbed or unabsorbed substance. This type of diarrhea has a high stool osmotic gap.

SECRETORY DIARRHEA: Diarrhea that results from secretion of water and electrolytes or decreased absorption and is characterized by a low stool osmotic gap.

STEATORRHEA: Characterized by greasy or oily stools that are difficult to flush. Patients with steatorrhea may often have nutritional deficiency secondary to malabsorption.

CLINICAL APPROACH TO ACUTE DIARRHEA

Pathophysiology

Diarrheal illnesses are extremely common, affecting nearly one in three people in the United States each year. In developing countries, acute infectious diarrhea is one of the leading causes of mortality. In the developed world, 90% of cases of acute diarrhea are infectious, but the large majority of those illnesses are mild and self-limited. Most causes of acute diarrhea in developed countries do not require antibiotic treatment and resolve with symptomatic treatment. High-risk groups include travelers, immunocompromised patients, and people who are hospitalized or institutionalized.

Most patients with mild-to-moderate illness do not require specific evaluation, and their symptoms can be managed with an oral sugar-electrolyte solution or with antimotility agents such as loperamide. Bismuth subsalicylate can also reduce symptoms of nausea and diarrhea. A more severe illness is suggested by any of the following findings: profuse watery diarrhea with signs of hypovolemia, grossly bloody stools, fever, symptoms lasting longer than 48 hours, severe abdominal pain, age > 70, hospitalization, or recent use of antibiotics.

For these patients, an evaluation should be performed to distinguish between inflammatory and noninflammatory causes of diarrhea. Routine evaluation includes testing for fecal leukocytes or fecal lactoferrin (a more sensitive marker of fecal leukocytes) and performing a routine stool culture (for Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter). Additional testing might include the following:

- Examination of stool for ova and parasites, which may be considered in cases of persistent diarrhea, especially if the patient has exposure to infants in a day care setting (Giardia, Cryptosporidium) or if there is a known community waterborne outbreak of these infections.

- Nonroutine cultures, such as for Escherichia coli O157:H7, may be performed in cases of acute bloody diarrhea, especially if there is a known local outbreak or if the patient develops hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS).

- Stool may also be tested for the Clostridium difficile toxin in patients with recent antibiotic use.

Treatment

Patients with inflammatory diarrhea may present with bloody stools, fever, or other signs suggestive of invasive bacterial or viral infections. The most common etiologies of inflammatory diarrhea are Salmonella, Campylobacter, Shigella, Entamoeba histolytica, and E. coli O157:H7. A patient with suspected inflammatory diarrhea often receives empiric antibiotics such as quinolones. An exception to this strategy is in patients with suspected enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) infection. There is no evidence of benefit from antibiotics for EHEC infections, such as those caused by the O157:H7 strain. Antibiotics are not recommended due to concerns for increased risk of HUS from an increase in the production of Shiga toxin.

If testing suggests a noninflammatory diarrhea, most cases are due to viral infection (Norwalk, rotavirus) food poisoning (Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus, Clostridium perfringens) or giardiasis. Viral infections and food poisoning are generally self-limited and are treated with supportive care. Giardiasis is treated with metronidazole or tinidazole.

CLINICAL APPROACH TO CHRONIC DIARRHEA

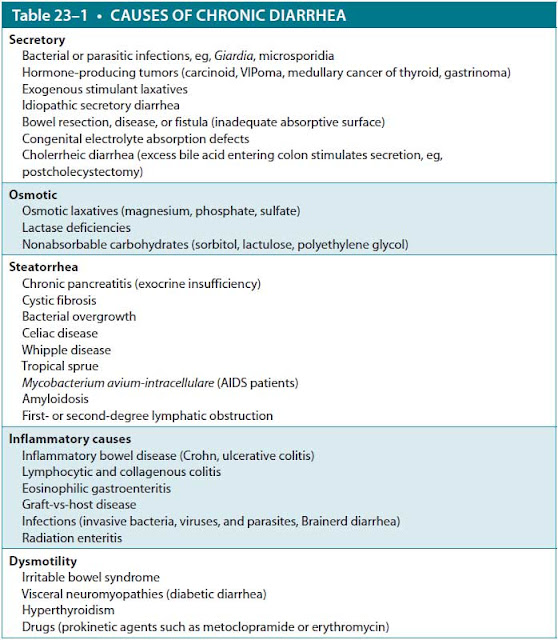

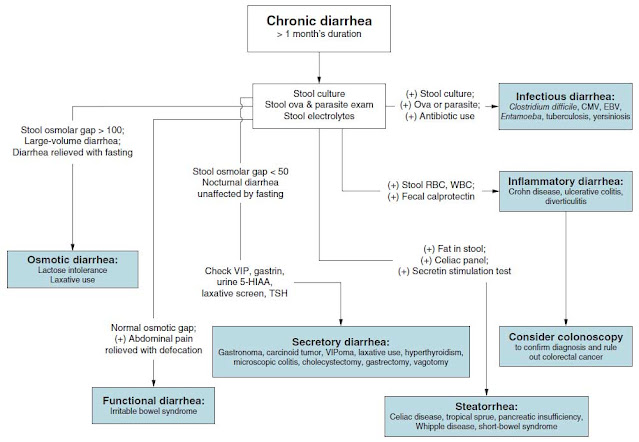

Unlike acute diarrhea, most cases of chronic diarrhea are not infectious. To evaluate and manage patients with chronic diarrhea, it is useful to classify the causes of chronic diarrhea by their pathophysiologic mechanism (Table 23–1 and Figure 23–1).

Abbreviation: VIPoma, vasoactive intestinal peptide tumor.

Secretory Diarrhea

Secretory diarrhea is caused by a disruption of the water and electrolyte transport across the intestinal epithelium. The diarrhea is typically described as large volume, watery, without significant abdominal pain, and with no evidence of stool fat or fecal leukocytes. Secretory diarrhea can occur while the patient is fasting or asleep.

Hormone-producing tumors are less common but important causes of secretory diarrhea. Carcinoid tumors typically arise in the small bowel and may present with diarrhea, episodic flushing, wheezing from bronchospasm, and right-sided heart failure. Diagnosis is established by demonstration of elevated serotonin levels, usually through finding high concentrations of its metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) in a 24-hour urine collection. Gastrinomas are uncommon

Figure 23–1. Diagnostic schema for chronic diarrhea.

neuroendocrine tumors that are usually located in the pancreas. These tumors secrete gastrin, which causes high gastric acid levels and manifests as recurrent peptic ulcers and diarrhea. Chronic diarrhea may be the presenting feature in 10% of cases. Initial diagnostic testing includes finding a markedly elevated fasting gastrin level. VIPoma is a rare pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor that secretes vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) as well as other peptide hormones that cause profuse, sometimes massive, watery diarrhea with profound dehydration and hypokalemia, as gastrointestinal (GI) secretions are rich in potassium.

Osmotic Diarrhea

Osmotic diarrhea occurs with ingestion of large amounts of poorly absorbed, osmotically active solute that draws water into the intestinal lumen. Common solutes include unabsorbed carbohydrates (sorbitol, lactulose, or lactose in patients with lactase deficiency), orlistat, or divalent ions (magnesium or sulfate, often used in laxatives). Low fecal pH < 6 suggests carbohydrate malabsorption. Other features of osmotic diarrhea include a high stool osmotic gap (> 75 mOsm/kg) and low sodium concentration (< 70 mEq/L). The fecal water output is proportional to the solute load, so the diarrhea can be large or small volume. An important clinical clue to distinguish between osmotic and secretory diarrhea is that secretory diarrhea will persist during a 24- to 28-hour fast, whereas osmotic diarrhea should abate with fasting or when the patient stops ingesting the poorly absorbed solute.

The most common cause of osmotic diarrhea is lactose intolerance, which affects the large majority of the world’s nonwhite population and approximately 20% to 30% of the US population. Most people lose the brush border lactase enzyme with age and can no longer digest lactose by adulthood. Diagnosis is made clinically, by history, and with a trial of lactose avoidance. Symptoms are managed by avoiding dairy products or providing supplementation with oral lactase enzyme.

Inflammatory Diarrhea

Inflammatory diarrhea is characterized by systemic symptoms such as fever, abdominal pain, and blood in the stool. Stool studies will typically show fecal leukocytes and an elevation of fecal calprotectin, which is released by neutrophils. The most common and important causes are the inflammatory bowel diseases, ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease. Microscopic colitis is another cause of inflammatory diarrhea that occurs in older adults and presents with frequent watery stools. Colonoscopy usually reveals normal colonic mucosa macroscopically, while biopsy shows lymphocytic infiltration.

Dysmotility

Dysmotility represents altered bowel motility due to a secondary cause, such as hyperthyroidism, prokinetic medications, or visceral autonomic dysregulation like diabetes. An extremely common but poorly understood dysmotility disorder is IBS. It is characterized by chronic abdominal pain and altered bowel habits without a clear organic cause. Pain is typically relieved with defecation, and there is often mucus discharge with stools and a sensation of incomplete voiding. Presence of any of the following findings is not characteristic of IBS and should prompt investigation for an organic cause of diarrhea: large-volume diarrhea, bloody stools, greasy stools, significant weight loss, anemia, occult or overt GI bleeding, or nocturnal awakening with pain or diarrhea.

Malabsorption/Steatorrhea

Malabsorption, or impaired absorption of nutrients, can be caused by either intraluminal maldigestion or mucosal epithelial defects. In conditions causing malabsorption, steatorrhea is commonly assessed as an indicator of global malabsorption primarily because the process of fat absorption is complex and is sensitive to interference from absorptive disease processes. Significant fat malabsorption produces greasy, foul-smelling diarrhea. Hydroxylation by gut bacteria leads to increased concentration of intraluminal fatty acids, causing an osmotic effect and increased stool output.

The most common cause of intraluminal maldigestion is pancreatic exocrine insufficiency due to chronic pancreatitis, most often due to alcohol abuse. Patients present with chronic abdominal pain, steatorrhea, and pancreatic calcifications on imaging and may often have diabetes due to pancreatic endocrine dysfunction and insulin deficiency. Other causes of chronic pancreatitis include hypertriglyceridemia, smoking, cystic fibrosis, and autoimmune pancreatitis. Treatment of malabsorption is with oral pancreatic enzyme supplementation.

The most common and important cause of mucosal malabsorption is celiac disease. It was originally described in pediatric patients with severe diarrhea and failure to thrive. It is now understood that this condition is much more common than previously recognized and affects approximately 1% of the population, with highest incidence in people of northern European ancestry. Patients with severe disease may present with classic manifestations of malabsorption: greasy, voluminous, foul-smelling stools; weight loss; severe microcytic anemia; neurologic disorders from deficiencies of B vitamins; and osteopenia from deficiency of vitamin D and calcium. However, this spectrum of findings is relatively uncommon, even in generalized mucosal disease. Adult patients with undiagnosed celiac disease rarely present with profuse diarrhea and severe metabolic disturbances. The majority of patients have relatively mild GI symptoms, which often mimic more common disorders, such as IBS, and may present solely with symptoms that are attributable to a nutritional deficiency or watery diarrhea. For example, patients with unexplained iron deficiency anemia, especially if it fails to correct adequately with iron supplementation, should be suspected to have celiac disease.

The exact pathophysiology of celiac disease is uncertain, but the current understanding is that genetically predisposed individuals, especially those with HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 gene subtypes, develop this immune disorder that is triggered by exposure to the gliadin component of gluten, which is a protein composite found in foods processed from wheat and related grain species like barley and rye.

In patients for whom there is a high clinical suspicion of disease, one should proceed to endoscopic evaluation with small-bowel biopsy, and a serologic evaluation. On an endoscopic examination, patients have characteristic mucosal changes involving villous atrophy and crypt hyperplasia in the proximal small bowel. IgA anti-EMA antibodies and anti- tTG antibodies are highly specific and reasonably sensitive tests for celiac disease. However, antigliadin antibodies have a lower specificity (between 2% and 12%). Patients who have no family history of celiac disease or no clinical or laboratory evidence of malabsorption have a low clinical suspicion of disease. In those cases, only serologic evaluation is sufficient for diagnosis. Negative serology adequately excludes the diagnosis in such patients. Note that all testing should be done with patients on a gluten-rich diet for at least several weeks, as the mucosal abnormalities may disappear and serologic titers fall after gluten withdrawal from the diet.

The mainstay of treatment of celiac disease is adherence to a gluten-free diet. Referral to a nutritionist may be appropriate, and there are a number of gluten-free foods that are commercially available. In addition, nutritional deficiencies should be corrected, and patients should be evaluated for bone loss using a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometric (DEXA) scan. Patients with celiac disease may also have a higher risk of GI tract malignancies and T-cell lymphoma, so one should maintain a high index of suspicion.

CASE CORRELATION

- See also Case 21 (Colitis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease) and Case 22 (Acute Diverticulitis).

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

23.1 A 24-year-old woman comes to the clinic due to intermittent diarrhea associated with abdominal pain for several months. She reports that her stools are watery and she sometimes sees mucus in the toilet. The episodes of diarrhea occur four to six times a day and last for a few days at a time. The patient denies any weight loss or fever. When questioned about her diet, the patient states that she eats a well-balanced diet and drinks three cups of coffee a day. Physical examination and rectal examination are normal. What is the most likely cause for this patient’s symptoms?

A. Altered mucosal permeability and GI motility

B. Transmural inflammation and tissue damage to intestinal walls

C. Decreased absorption of disaccharides in the small intestine

D. Exocrine insufficiency resulting in maldigestion

E. Immunologic response resulting in intestinal mucosal atrophy and crypt hyperplasia

23.2 A 65-year-old man presents to his provider because of watery diarrhea for the last 4 months. He denies passing bloody stools, but he has had up to nine large-volume bowel movements a day. He noticed that he has lost 10 lb in the last month, which he attributes to lack of appetite and nausea. He has had extreme fatigue and finds it difficult to go about his daily routine. The patient also complains of numbness and tingling of his lower extremities. He is afebrile and has a blood pressure reading of 105/70 mm Hg. On physical examination, the patient has mild, diffuse tenderness to palpation of the abdomen without guarding. The provider notes that the patient’s mucous membranes appear dry. Abnormal laboratory tests include a K+ level of 3.1 mmol/L and Ca2+ level of 11.2 mg/dL. What is the most appropriate next step in diagnosis?

A. Computed tomographic (CT) scan of the abdomen

B. Serum VIP level

C. Gallium Ga-68 DOTATATE positron emission tomographic (PET)/CT scan

D. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy

E. Endoscopic ultrasound

F. Exploratory laparotomy

23.3 Which of the following patients is not a good candidate for evaluation for celiac disease with either endoscopy or serologic testing?

A. A 26-year-old woman who experiences intermittent abdominal bloating but no diarrhea and is found to have osteopenia and vitamin D deficiency.

B. A 19-year-old college freshman with bulky, foul-smelling, floating stools and excessive flatulence who has lost 20 lb unintentionally.

C. A thin, 39-year-old man with a family history of celiac disease who has been adhering to a gluten free vegetarian diet for the last 3 years and now complains of gassiness and reflux.

D. A 42-year-old man who was found to have iron deficiency anemia but has no GI symptoms and recently had a negative colonoscopy.

23.4 A 29-year-old man presents to the clinic due to 3 days of abdominal cramps and diarrhea. His diarrhea was initially watery but progressed to bloody episodes. He has had a low-grade fever and reports two episodes of vomiting. The patient says that he recently returned from a trip to Mexico. Physical examination shows mild dehydration and minimal blood in the rectal vault. What is the most appropriate treatment for this patient?

A. Metronidazole

B. Azithromycin

C. Vancomycin and cefepime

D. Piperacillin-tazobactam

E. Observation and supportive care

ANSWERS

23.1 A. This patient’s symptoms are most suggestive of IBS. IBS is diagnosed based on the Rome IV criteria, which include abdominal pain at least 1 day per week for at least 3 months associated with two or more of the following criteria: (1) pain related to defecation, (2) change in frequency of stool, and (3) change in appearance of stool. IBS is a diagnosis of exclusion and should not be made if the patient has “alarm” symptoms (hematochezia, weight loss, anemia). This patient has mucus in her stools, which is a common complaint. IBS causes altered gut motility, although the pathophysiology is not clear. Transmural inflammation (answer B) is seen in Crohn disease, which would also present with systemic symptoms. Lactose intolerance is caused by decreased absorption of disaccharides (answer C). Chronic pancreatitis presents with exocrine insufficiency and maldigestion (answer D). Celiac disease causes an immunologic response to gliadin, which leads to crypt hyperplasia and villous atrophy (answer E).

23.2 B. This patient presents with voluminous watery diarrhea, dehydration, weight loss, hypokalemia, and hypercalcemia, which suggest VIPoma. VIPomas are caused by autonomous VIP secretion leading to stimulation of intestinal epithelial cells and fluid secretion into the lumen. This tumor can lead to iron and vitamin B12 deficiencies. The best initial step to confirm diagnosis is to obtain a serum VIP level. After diagnosis is confirmed, a CT scan of the abdomen (answer A) is usually obtained to confirm location of the tumor as well as help with staging; an initial CT scan is not indicated without a diagnosis. DOTATATE scans (answer C) and somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (answer D) are used if other imaging is inconclusive. In addition to initial workup and repletion of electrolytes, this patient may require testing for multiple endocrine neoplasia type I syndrome. The other answer choices, endoscopic ultrasound (answer E) and exploratory laparotomy (answer F), are not useful for this condition.

23.3 C. While GI symptoms in a patient with a family history of celiac disease are reasonable to investigate, the fact that he has been on a gluten-free diet for a prolonged period greatly diminishes the sensitivity of both endoscopic and serologic testing. Unexplained osteopenia and vitamin D deficiency in a young woman (answer A), unexplained iron deficiency anemia (answer D) in any patient, and the classic presentation with steatorrhea and weight loss (answer B) should all be investigated.

23.4 E. Acute diarrhea that progresses to bloody diarrhea and a history of recent travel suggests EHEC infection. Empiric antibiotics (answers A-D) are not used in EHEC infections due to the risk of developing HUS. Although there is less data in adults, the risk for HUS in children rises as high as 25% when treated with antibiotics. Antibiotics have also not been shown to reduce GI upset symptoms. The best treatment for a patient with suspected EHEC infection is supportive care with isotonic fluids.

CLINICAL PEARLS

▶ Most cases of acute infectious diarrhea in the United States cause mild-to-moderate illness that is self-limited and can be managed with oral rehydration solution or with antimotility agents such as loperamide.

▶ Empiric treatment with quinolone antibiotics is usually indicated for acute inflammatory diarrhea. An exception is for EHEC infection, where antibiotics may increase the risk of HUS.

▶ Symptoms of malabsorption include greasy, voluminous stools; weight loss; anemia; neurologic disorders from deficiencies of B vitamins; and osteopenia from deficiency of vitamin D and calcium.

▶ Adults with undiagnosed celiac disease often present with relatively mild GI symptoms and may only present with unexplained nutritional deficiency, such as refractory iron deficiency anemia.

▶ If there is a high clinical suspicion for celiac disease, patients should undergo endoscopic evaluation with small-bowel biopsy and serologies for IgA anti-EMAs and anti-tTG antibodies.

REFERENCES

AGA Institute. AGA Institute Medical position statement on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(6):1977.

Bergsland, E. VIPoma: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management. Tanabe KK, Whitcomb DC, Grover S, eds. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2019. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vipoma-clinical-manifestations-diagnosis-and-management. Accessed July 17, 2019.

Binder HJ. Disorders of absorption. In: Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 19th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Education; 2015:1932-1946.

Camilleri M, Murray JA. Diarrhea and constipation. In: Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 19th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Education; 2015:264-274.

Camilleri M, Sellin JH, Barrett KE. Pathophysiology, evaluation, and management of chronic watery diarrhea. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:515-532.

Ciclitira PJ. Management of celiac disease in adults. Lamont JT, Grover S, eds. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2019. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/management-of-celiac-disease-in-adults. Accessed July 17, 2019.

Kelly CP. Diagnosis of celiac disease in adults. Lamont JT, Grover S, eds. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2019. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnosis-of-celiac-disease-in-adults. Accessed July 17, 2019.

Lacy BE, Patel NK. Rome criteria and a diagnostic approach to irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Med. 2017;6(11):99.

LaRocque R, Harris JB. Approach to the adult with acute diarrhea in resource-rich settings.

Calderon SB, Bloom A, eds. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2019. https://www.uptodate

.com/contents/approach-to-the-adult-with-acute-diarrhea-in-resource-rich-settings. Accessed July 17, 2019.

Schuppan D. Pathogenesis, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations of celiac disease in adults. Lamont JT, Grover S, eds. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2019. https://www.uptodate

.com/contents/pathogenesis-epidemiology-and-clinical-manifestations-of-celiac-disease-in-adults. Accessed July 17, 2019.

Sweetser S. Evaluating the patient with diarrhea: a case-based approach. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(6):596-602.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.