Cubital Tunnel Syndrome Case File

Eugene C. Toy, MD, Andrew J. Rosenbaum, MD, Timothy T. Roberts, MD, Joshua S. Dines, MD

CASE 28

A 45-year-old right-hand dominant woman presents to the orthopaedic hand clinic with a 6-month history of right hand numbness and tingling. She denies any trauma or inciting incident but reports that she noticed the numbness and tingling after waking up one morning. The symptoms come and go throughout the day and are worse in the night time, waking her up 3 to 4 times a week. Over the past month, her symptoms have gotten progressively worse, with some days of constant numbness. She denies any symptoms in her neck, shoulder, or arm. She denies any pain. She reports feeling weaker in her right hand, especially with opening a bottle or buttoning her shirt. Over the last few months, her right hand has fatigued faster than her left.

On physical exam, she has full active range of motion of her neck, right shoulder, elbow, wrist, and fingers. Focused exam of her right upper extremity reveals no gross deformity or muscle atrophy. She has ulnar deviation of her small ringer. There is no erythema, ecchymosis, or effusions. She localizes her numbness to her ring and small fingers and cannot discern whether the symptoms are dorsal or volar. On strength testing, she has 5/5 strength of her biceps, triceps, wrist extensors/flexors, thumb extensors/flexors, and flexors of her index and middle finger. She has 3/5 strength of her hand intrinsics and the flexors of her ring and small finger. She has normal sensation to light touch but decreased sensation to pinprick over the volar and dorsal ulnar aspect of her hand. She has a 2+ radial pulse and normal Allen test. Elbow, wrist, and hand radiographs are negative for any pathology.

► What is the most likely diagnosis?

► What muscles does this disease process affect?

► What is your next diagnostic step?

► What are the treatment options?

ANSWER TO CASE 30:

Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

Summary: A 45-year-old right-hand dominant woman presents with 6 months of right hand numbness, tingling, and now weakness. She denies any history of trauma or specific inciting event and states that her symptoms have worsened over the last month. On exam there is no gross deformity or muscle atrophy of her right upper extremity, but weakness of her intrinsics and ring and small finger flexors is observed. She also has decreased sensation to pinprick over the volar and dorsal ulnar aspect of her hand.

- Most likely diagnosis: Cubital tunnel syndrome.

- Affected muscles: Flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU), hand intrinsics (lumbricals for ring and small finger, dorsal interossei, palmar interossei), hypothenar muscles (palmaris brevis, abductor digiti minimi, opponens digiti minimi, flexor digiti minimi), flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) for ring and small finger, adductor pollicis, deep head of flexor pollicis brevis.

- Next diagnostic step: Electrodiagnostic testing.

- Treatment options: Nonsurgical options include bracing, activity modifications, and physical therapy, whereas surgery involves ulnar nerve decompression at the cubital tunnel.

ANALYSIS

Objectives

- Understand the anatomy of the ulnar nerve and the potential sites of compression.

- Understand the physical exam findings and electromyelogram (EMG) analysis associated with ulnar nerve entrapment.

- Know the treatment options for cubital tunnel syndrome.

Considerations

This 45-year-old woman presents complaining of symptoms concerning for an entrapment neuropathy. The first priority is to perform a thorough history, which will help in narrowing down the possible diagnoses. This patient denies any trauma or inciting event, and her symptoms (right hand numbness, tingling, and weakness), which have become more constant over the last month, typically wax and wane throughout the day and are most severe at night. Given this history, the practitioner must consider the entrapment neuropathies of the upper extremity in the differential diagnosis. This includes carpal tunnel and cubital tunnel syndromes. A focused physical exam of the right upper extremity will further aid the clinician in determining the diagnosis. This includes ruling out cervical spine pathology that can cause similar symptoms, as well as a brachial plexopathy. In this specific case, for which ulnar nerve entrapment is likely, plain radiographs should be obtained and electrodiagnostic testing performed. Treatment options can then be discussed pending confirmation of the diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome.

APPROACH TO:

Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

DEFINITIONS

TINEL TEST: A way to detect irritated nerves. It is performed by lightly tapping or percussing over a given nerve to elicit a sensation of “tingling” or “pins and needles” in the distribution of the nerve.

FROMENT SIGN: A test for ulnar nerve palsy that specifically assesses the action of the adductor pollicis (ulnar nerve innervated). The patient is asked to hold a piece of paper between the thumb and index finger. Normally, as the examiner attempts to pull the paper away, an individual will be able to maintain a hold on the paper with little or no difficulty. However, the patient with ulnar nerve palsy will flex the thumb via the flexor pollicis longus (innervated by the anterior interosseous branch of the median nerve) to try to maintain a hold on the paper.

WARTENBERG SIGN: A sign noting the position of abduction and extension assumed by the small finger in the setting of cubital tunnel syndrome.

CLINICAL APPROACH

Anatomy

Cubital tunnel syndrome, the second most common upper-extremity compressive neuropathy after carpal tunnel syndrome, is a term used to describe symptoms related to ulnar nerve compression and/or traction around the elbow. Cubital tunnel syndrome includes any ulnar neuropathy in the mid-arm to mid-forearm.

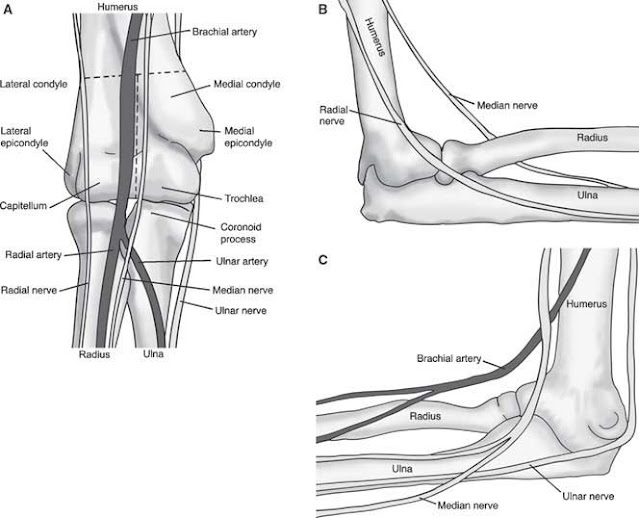

The ulnar nerve is the terminal branch of the medial cord of the brachial plexus (C8-T1). The nerve courses between the medial head of the triceps and the brachialis muscle before coursing posterior to the medial epicondyle and entering the cubital tunnel. The tunnel’s anatomic borders are as follows: Anterior, medial epicondyle; posterior, olecranon; floor, medial collateral ligament; roof, arcuate ligament. After leaving the cubital tunnel, the ulnar nerve passes into the forearm between the 2 heads of the FCU and exits under the deep flexor pronator aponeurosis. At this point it lies deep to the FDS and FCU and superficial to the FDP. There are several major sites at which the ulnar nerve often becomes compressed (Figure 30–1):

1. Arcade of Struthers: Band of fascia connecting the medial head of the triceps with the medial intermuscular septum, approximately 7 to 10 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle

2. Medial intermuscular septum

3. Medial head of triceps: Can become hypertrophied in bodybuilders

Figure 30–1. Elbow anatomy. (A) Anterior view, (B) lateral view, and (C) medial view. (Reproduced,

with permission, from Tintinalli J, et al. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2010:Fig. 267-1.)

4. Medial epicondyle: Can cause compressive or traction forces via deformity from a prior supracondylar fracture (Tardy ulnar nerve palsy owing to development of progressive valgus deformity associated with these fractures) or osteophytes in an arthritic elbow

5. Arcuate ligament: The roof of the cubital tunnel

6. Osborne fascia: This is the proximal fibrous edge of the FCU and most common site of ulnar nerve compression

7. Epicondylar groove: A shallow groove increasing risk of ulnar nerve subluxation; a site where external compression can occur from leaning on a flexed elbow for prolonged period of time

8. Anconeus epitrochlearis: Accessory muscle arising from medial olecranon and triceps and inserting on the medial epicondyle; seen in 10% of patients undergoing cubital tunnel release

9. Deep flexor pronator aponeurosis

Physical Exam

Patients often present with poorly localized numbness and tingling in their hand. At times they are able to localize the symptoms in an ulnar nerve distribution.

The symptoms can be occasional or constant and exacerbated by elbow flexion. With longstanding ulnar nerve compression, patients may have wasting of their intrinsic muscles and hand weakness. An intrinsic minus or claw hand (hyperextension of the metacarpal phalangeal joints and flexion of the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints) may result from longstanding compression. Look for a Wartenberg sign (ulnar deviation of the small finger)—patients complain of inability to put their hand in their pocket or their small finger getting caught on things. Patients may have weakness of their pinch and compensate by flexing the thumb interphalangeal joint during pinching (Froment sign).

Patients may complain of medial elbow pain and have a positive Tinel test (exacerbation of the ulnar hand numbness by tapping on the ulnar nerve). It is important to do a thorough neck and shoulder exam to rule out nerve compression proximal to the elbow. This includes cervical range of motion to evaluate for associated pain and/or radiculopathy. Range the elbow and evaluate for ulnar nerve subluxation. The functional range of motion of the elbow is 30 to 130 degrees. The normal carrying angle is 7 to 15 degrees. Sensation in the hand should also be examined.

Radiographs of the elbow should be evaluated for osseous causes of compression (ie, osteophytes). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), although not typically indicated, can identify space-occupying lesions or edema within the nerve. Electrodiagnostic testing, which includes EMG and nerve conduction studies, is the gold standard to evaluate for ulnar neuropathy. Nerve conduction studies are considered positive if the motor conduction velocity across the elbow is less than 52 m/s, increased distal sensory latency of greater than 3.2 ms, and motor latencies of greater than 5.3 ms. Of note, abnormal EMG results are associated with poor surgical outcomes.

TREATMENT

To determine the appropriate treatment for a patient with cubital tunnel syndrome, the following considerations must be taken into account: patient compliance, worker’s compensation, occupation, age, comorbidities, duration of symptoms, and severity of symptoms. Additionally, the orthopaedist must be certain that other causes of the patient’s symptoms have been ruled out and that concurrent carpal tunnel syndrome (present in 40% of patients with cubital tunnel syndrome) is not present, which often requires simultaneous release.

For patients with mild cubital tunnel syndrome, nonsurgical options can alleviate symptoms and help prevent long-term nerve damage. A splint that keeps the elbow at approximately 70 degrees of flexion, especially when worn at night, can alleviate symptom exacerbation. Physical therapy (PT) that works on nerve mobilization and gliding, in addition to activity modification, can also aid in symptom relief. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as well as soft elbow padding can also be used.

For patients with constant numbness/tingling, muscle atrophy, muscle weakness, or severe slowing of conduction velocity, surgical intervention is recommended. Surgery includes decompressing the nerve with or without transposition. This is achieved via in situ decompression (decompressing the nerve and leaving it where it is), subcutaneous transposition (moving the nerve anterior to the medial epicondyle), intramuscular transposition (moving the nerve into an area surrounded by the flexor-pronator muscles), submuscular transposition (moving the nerve under the flexor-pronator muscles), and medial epicondylectomy (removing part of the medial epicondyle). The cubital tunnel can also be released endoscopically.

Most cases of cubital tunnel syndrome requiring surgical intervention can be treated with in situ decompression. There are inherent risks with nerve transposition, including compromised blood supply, nerve scarring, injury to adjacent structures, and a longer incision. Studies have shown that in situ decompression is adequate for most patients and has equivalent outcomes to decompression with transposition. Patients with a hypermobile nerve will likely benefit from moving the nerve to a new location.

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

30.1 A 40-year-old left-hand dominant man presents with an 8-month history of left hand numbness, tingling, and now weakness. On exam, you note a positive Froment sign. The patient subsequently undergoes electrodiagnostic testing, which is consistent with cubital tunnel syndrome. The cubital tunnel is formed by which structures?

A. Anterior, lateral epicondyle; posterior, olecranon; floor, medial collateral ligament; roof, arcuate ligamentB. Anterior, medial epicondyle; posterior, olecranon; floor, medial collateral ligament; roof, arcuate ligamentC. Anterior, lateral epicondyle; posterior, olecranon; floor, lateral collateral ligament; roof, arcuate ligamentD. Anterior, medial epicondyle; posterior, humerus; floor, medial collateral ligament; roof, arcuate ligament

30.2 A 50-year-old man complains of numbness and tingling along his right small finger. Elbow flexion reproduces the numbness and tingling. Physical therapy and splinting have failed to relieve the symptoms over the last 3 months. Which of the following is the most appropriate intervention?

A. In situ ulnar nerve decompression at the cubital tunnelB. Ulnar nerve decompression at the cubital tunnel with anterior submuscular transpositionC. Ulnar nerve decompression at the cubital tunnel with anterior subcutaneous transpositionD. Continued physical therapy, splinting, and conservative management

30.3 An amateur bodybuilder presents with physical examination findings concerning for an ulnar nerve compression neuropathy. Which of the following anatomic locations is more commonly associated with ulnar nerve compression in bodybuilders as compared with the regular population?

A. Osborne fasciaB. Arcuate ligamentC. Medial epicondyleD. Medial head of the triceps

ANSWERS

30.1 B. The cubital tunnel is formed by the medial epicondyle anteriorly and the olecranon posteriorly. The medial collateral ligament forms the floor, and the roof consists of the arcuate ligament.

30.2 A. The patient has cubital tunnel syndrome that has failed conservative management. In situ decompression of the ulnar nerve is less invasive and has clinical outcomes equivalent to that of decompression with transposition. Decompression with transposition has also been shown to have higher complication rates.

30.3 D. All of the choices are possible sites of ulnar nerve compression, even in bodybuilders. However, hypertrophy of the medial head of the triceps in this population can cause ulnar neuropathy. This is an uncommon site of compression in the general population.

CLINICAL PEARLS

|

► Cubital tunnel syndrome includes any ulnar neuropathy in the mid-arm to mid-forearm. ► The anatomic borders of the cubital tunnel are as follows: Anterior, medial epicondyle; posterior, olecranon; floor, medial collateral ligament; roof, arcuate ligament. ► Nerve conduction studies are considered positive if the motor conduction velocity across the elbow is less than 52 m/s, increased distal sensory latency of greater than 3.2 ms, and motor latencies of greater than 5.3 ms. ► Conservative management of cubital tunnel includes splinting, NSAIDs, elbow padding, and PT. ► Operative interventions include ulnar nerve decompression with or without transposition and/or medial epicondylectomy. |

REFERENCES

Grana W. Medial epicondylitis and cubital tunnel syndrome in the throwing athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2001;20:541-548. Review.

Palmer BA, Hughes TB. Cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35:153-163.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.