Endocarditis (Tricuspid)/Septic Pulmonary Emboli Case File

Eugene C. Toy, MD, Gabriel M. Aisenberg, MD

Case 12

A 28-year-old man comes to the emergency center complaining of 6 days of fever with shaking chills. Over the past 2 days, he has also developed a productive cough with greenish sputum, occasionally streaked with blood. He reports no dyspnea, but sometimes he experiences chest pain with deep inspiration. He does not have a headache, abdominal pain, urinary symptoms, vomiting, or diarrhea. He has no significant past medical history. He smokes cigarettes and marijuana regularly, drinks several beers daily, and denies intravenous drug use.

On examination, his temperature is 102.5 °F, heart rate is 109 beats per minute (bpm), blood pressure is 128/76 mm Hg, and respiratory rate is 23 breaths per minute. He is alert and talkative. He has no oral lesions, and fundoscopic examination reveals no abnormalities. His jugular veins show prominent V waves. He is tachycardic with a regular rhythm and has a harsh holosystolic murmur

at the left lower sternal border that becomes louder with inspiration. Chest examination reveals inspiratory rales bilaterally. He has linear streaks of induration, hyperpigmentation, and a few small nodules overlying the superficial veins on either forearm, but no erythema, warmth, or tenderness.

Laboratory examination is significant for an elevated white blood cell count of 17,500/mm3, with 84% polymorphonuclear cells, 7% band forms, and 9% lymphocytes; a hemoglobin concentration of 14 g/dL; hematocrit of 42%; and platelet count of 189,000/mm3. Liver function tests and urinalysis are normal. A chest radiograph shows multiple peripheral, ill-defined nodules, some with cavitation.

▶ What is the most likely diagnosis?

▶ What is your next step?

ANSWERS TO CASE 12:

Endocarditis (Tricuspid)/Septic Pulmonary Emboli

Summary: A 28-year-old man presents with

- Complaints of shaking chills, fever, and a productive cough

- Denial of intravenous drug use

- A new holosystolic murmur at the left lower sternal border that increases with inspiration

- Linear streaks of induration on both forearms

- Chest radiograph showing multiple ill-defined nodules

Most likely diagnosis: Infective endocarditis involving the tricuspid valve, with probable septic pulmonary emboli.

Next step: Obtain serial blood cultures and institute empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics.

- Describe the differences in clinical presentation between acute and subacute endocarditis and between left-sided versus right-sided endocarditis. (EPA 1, 2)

- Identify the most common organisms that cause endocarditis, including “culture-negative” endocarditis. (EPA 2, 3, 4)

- Review the diagnostic approach to infective endocarditis, including the indications for valve replacement. (EPA 4)

- Understand the complications of endocarditis, which include valvular and embolic sequelae. (EPA 4, 10)

- Discuss management principles for infectious endocarditis and implications for antibiotic and anticoagulant use. (EPA 4, 12)

Considerations

Although this patient denied intravenous drug use, the track marks on the forearms are very suspicious for intravenous drug abuse. This type of addiction carries a social stigma, which is the usual reason for patients not to disclose it. A polite, nonjudgmental approach makes patients more open to discuss this medical problem. This patient has fever, a new heart murmur very typical of tricuspid regurgitation, and a chest radiograph suggestive of multiple septic pulmonary emboli. Serial blood cultures, ideally obtained before antibiotics are started, are essential to establish the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. The rapidity with which antibiotics are started depends on the clinical presentation of the patient: A septic, critically ill patient needs antibiotics immediately, whereas a patient with a subacute presentation can wait many hours while cultures are obtained.

DEFINITIONS

D-DIMERS: Protein fragments present in the blood after a blood clot gets degraded during fibrinolysis, used for suspicion of deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or disseminated intravascular coagulation.

INFECTIOUS ENDOCARDITIS: A microbial inflammation of the endocardium, usually involving the heart valves.

JANEWAY LESIONS: Painless hemorrhagic macules on the palms and soles thought to be caused by septic emboli, resulting in microabscesses.

LOW-MOLECULAR-WEIGHT HEPARIN: A class of anticoagulants that works by activating antithrombin, which decreases factor Xa in the coagulation cascade, preventing the formation of a clot.

OSLER NODES: Painful, palpable, erythematous lesions most often involving the pads of the fingers and toes, representing vasculitic lesions caused by immune complexes.

ROTH SPOTS: Hemorrhagic retinal lesions with white centers thought to be an immune complex–mediated vasculitis. While this term is widely accepted, the description of these lesions should actually be attributed not to Roth, but to Litten.

CLINICAL APPROACH

Pathophysiology and Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of infectious endocarditis varies between patients depending on which valves are involved (left sided vs right sided), as well as the virulence of the organism. Highly virulent species, such as Staphylococcus aureus, produce a rapidly progressive endocarditis. Conversely, less virulent organisms, such as Streptococcus viridans or mutans, produce a more subacute endocarditis, which may evolve over weeks. Fever is present in 95% of all cases. For acute endocarditis, patients often present with high fever, acute valvular regurgitation, and embolic phenomena (eg, to the extremities or to the brain, causing stroke). Subacute endocarditis is more often associated with constitutional symptoms such as anorexia, weight loss, night sweats, and findings attributable to immune complex deposition and vasculitis; these include petechiae, splenomegaly, and glomerulonephritis. Classic peripheral lesions, such as Osler nodes, Janeway lesions, and Roth spots, although frequently discussed, are seen in only 20% to 25% of cases. Splinter hemorrhages under the nails may also be seen, but this finding is very nonspecific. A common mnemonic used to remember the clinical features of bacterial endocarditis is “FROM JANE,” which stands for fever, Roth spots, Osler nodes, murmur, Janeway lesions, anemia, nail bed hemorrhage, and emboli.

Right-sided endocarditis usually involves the tricuspid valve, causing pulmonary emboli, rather than involving the systemic circulation. Accordingly, patients develop pleuritic chest pain, purulent sputum, or hemoptysis, and radiographs may show multiple peripheral nodular lesions, often with cavitation. The murmur of tricuspid regurgitation may not be present, especially early in the illness.

In all cases of endocarditis, the critical finding is bacteremia, which usually is sustained. The initiating event is a transient bacteremia, which may be a result of mucosal injury, such as a dental extraction, or a complication from the use of intravascular catheters. Bacteria are then able to seed valvular endothelium. Previously damaged, abnormal, or prosthetic valves form vegetations, which are composed of platelets and fibrin and are relatively avascular sites where bacteria may grow protected from immune attack.

An uncommon situation in which routine cultures fail to grow is most likely a result of prior antibiotic treatment, fungal infection (fungi other than Candida spp often require special culture media), or fastidious organisms. These organisms can include Abiotrophia spp, Bartonella spp, Coxiella burnetii, Legionella spp, Chlamydia, and the HACEK organisms (Haemophilus aphrophilus/paraphrophilus, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, Kingella kingae).

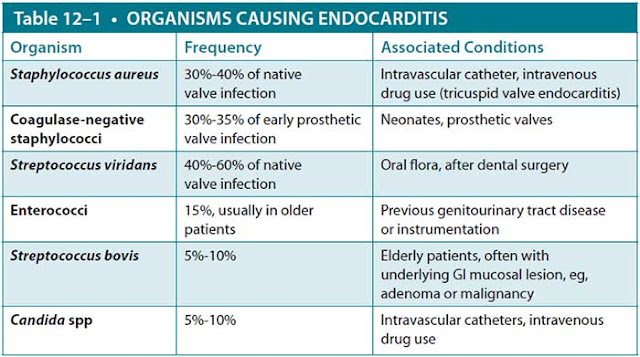

Serial blood cultures are the most important step in the diagnosis of endocarditis. Acutely ill patients should have three blood cultures obtained over a 2- to 3-hour period prior to initiating antibiotics. In subacute disease, three blood cultures over a 24-hour period maximize the diagnostic yield. If patients are critically ill or hemodynamically unstable, initiation of antibiotic therapy should not be delayed while cultures are obtained. Because sustained bacteremia is the hallmark of infective endocarditis, blood cultures are commonly positive for microorganisms. Table 12–1 lists typical organisms, frequency of infection, and associated conditions.

Clinical features and echocardiography are also used to diagnose cases of infective endocarditis using the highly sensitive and specific Duke criteria. Endocarditis is considered to definitely be present if the patient satisfies two major criteria, one major and three minor criteria, or five minor criteria (Table 12–2). It should be noted that transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) rather than transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is the method of choice in assessing these vegetations due to better image quality and fewer intervening structures. If concerns for systemic embolization arise, D-dimer testing is helpful, with an elevated level indicating significant blood clot formation and breakdown in the body.

Treatment

Antibiotics. Antibiotic treatment is usually begun in the hospital, but because of the prolonged nature of therapy, it is often completed on an outpatient basis once the patient is clinically stable. Treatment generally lasts 4 to 6 weeks. If the organism is susceptible to beta-lactams, such as most Streptococcus species, penicillin G is the

agent of choice. For S. aureus, nafcillin is the drug of choice, often used in combination with gentamicin, initially for synergy, to help resolve bacteremia. Therapy for intravenous drug users should be directed against S. aureus. Vancomycin is used when methicillin-resistant S. aureus or coagulase-negative staphylococci are present. Ceftriaxone is the usual therapy for the HACEK group of organisms. Deciding appropriate therapy for culture-negative endocarditis may be challenging and depends on the clinical situation.

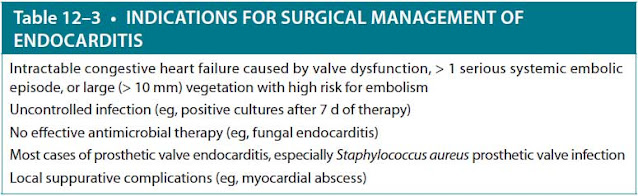

Surgery and Anticoagulation. Table 12–3 summarizes the commonly recognized indications for surgical intervention: valve excision and replacement. For patients with isolated or newly diagnosed infectious endocarditis, routine anticoagulation is not recommended unless there is a preexisting or coexisting condition warranting treatment, such as atrial fibrillation, stroke, deep vein thrombosis, or pulmonary embolism. At this time, if there are no other contraindications to anticoagulation, low-molecular-weight heparin, fondaparinux, or oral factor Xa inhibitors can be used.

Antibiotic Prophylaxis. Patients at high risk for developing infective endocarditis benefit from antibiotic prophylaxis prior to dental procedures. The most recent American Heart Association guidelines (2007) specify individuals the following conditions

- Prosthetic heart valves

- Previous infective endocarditis

- Congenital heart disease (unrepaired cyanotic coronary heart disease [CHD], including palliative shunts and conduits)

- CHD completely repaired with prosthetic material or a device during the first 6 postoperative months

- Repaired CHD with residual defects at the site or adjacent to the site of a prosthetic patch or prosthetic device

- Valve regurgitation caused by a structurally abnormal valve in cardiac transplant recipients

Amoxicillin is the drug of choice for prophylaxis unless the patient is allergic to penicillin or unable to take medications by mouth. In these situations, alternative antibiotics such as cephalosporins and clindamycin can be used.

Complications

One life-threatening complication of endocarditis is congestive heart failure, usually as a consequence of infection-induced valvular damage. Other cardiac complications are intracardiac abscesses and conduction disturbances caused by septal involvement by infection. Systemic arterial embolization may lead to splenic or renal infarction, as well as abscess formation. Vegetations may embolize to the coronary circulation, causing a myocardial infarction, or to the brain, causing a cerebral infarction. A stroke syndrome in a febrile patient should always suggest the possibility of endocarditis. Infection of the vasa vasorum may weaken the wall of major arteries and produce mycotic aneurysms, which occur most commonly in the cerebral circulation, sinuses of Valsalva, or abdominal aorta. These aneurysms may leak or rupture, producing sudden intracranial hemorrhage or exsanguination.

CASE CORRELATION

- See also Case 3 (Acute Coronary Syndrome), Case 5 (Aortic Dissection/ Marfan Syndrome), and Case 9 (Syncope and Heart Block).

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

12.1 A 68-year-old man was hospitalized with persistent fever and a new heart murmur and diagnosed with Streptococcus bovis endocarditis of the mitral valve. After receiving 10 days of intravenous antimicrobial therapy, he is noted to be afebrile and with symptoms resolved. At this time, which of the following is the most important next step?

A. Good dental hygiene and proper denture fitting to prevent reinfection of damaged heart valves from oral flora.

B. Repeat echocardiography in 6 weeks to ensure the vegetations have resolved.

C. Colonoscopy to look for mucosal lesions.

D. Mitral valve replacement to prevent systemic emboli such as cerebral infarction.

12.2 A 24-year-old intravenous drug user is admitted to the hospital with 4 weeks of fever. He has three blood cultures positive for growth of Candida species. After 2 days in the hospital, he develops a cold, blue right great toe. Which of the following is the appropriate next step?

A. Repeat echocardiography to see if the large aortic vegetation previously seen has now embolized.

B. Cardiovascular surgery consultation for aortic valve replacement.

C. Aortic angiography to evaluate for a mycotic aneurysm, which may be embolizing.

D. Switch from fluconazole to amphotericin B.

12.3 A patient with which of the following conditions requires antimicrobial prophylaxis before dental surgery?

A. Atrial septal defect

B. Mitral valve prolapse without mitral regurgitation

C. Previous coronary artery bypass graft

D. Previous infective endocarditis

ANSWERS

12.1 C. Colonoscopy is necessary because a significant number of patients with S. bovis endocarditis have a colonic cancer or premalignant polyp, which leads to seeding of the valve by gastrointestinal (GI) flora. Heart valves damaged by endocarditis are more susceptible to infection, so good dental hygiene (answer A) is important, but in this case, the organism came from the intestinal tract, not the mouth, and the possibility of malignancy is most important to address. Serial echocardiography (answer B) would not add to the patient’s care after successful therapy because vegetations become organized and persist for months or years without late embolization. Prophylactic valve replacement (answer D) would not be indicated because the prosthetic valve is even more susceptible to reinfection than the damaged native valve and would actually increase the risk of cerebral infarction or other systemic emboli as a consequence of thrombus formation, even if adequately anticoagulated.

12.2 B. Fungal endocarditis, which occurs in intravenous drug users or immunosuppressed persons with indwelling catheters, frequently gives rise to large, friable vegetations with a high risk of embolization (often to the lower extremities) and is very difficult to cure with medical therapy (antifungal medications). Valve replacement is usually necessary. Repeat echocardiography (answer A) would not add to the patient’s care because the clinical diagnosis of peripheral embolization is almost certain, and it would not change the management. Mycotic aneurysms (answer C) may occur in any artery as a consequence of endocarditis and can cause late embolic complications, but in this case, the source probably is the heart. Medical therapy with any antifungal agent (answer D) is unlikely to cure this infection.

12.3 D. Prior endocarditis damages valvular surfaces, and these patients are at increased risk for reinfection during a transient bacteremia, as may occur during dental procedures or some other GI or genitourinary tract procedures. All of the other conditions mentioned (answer A, atrial septal defect; answer B, mitral valve prolapse without mitral regurgitation; and answer C, previous coronary artery bypass graft) have a negligible risk of endocarditis, the same as in the general population, and antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended by the American Heart Association.

CLINICAL PEARLS

▶ Suspect endocarditis in a patient with a fever or signs of bacteremia and a new heart murmur.

▶Infective endocarditis is diagnosed in patients with sustained bacteremia and evidence of endocardial involvement, usually by echocardiography.

▶Right-sided endocarditis may be difficult to diagnose due to the lack of systemic emboli seen in left-sided endocarditis and because a tricuspid regurgitation murmur is often not heard.

▶Left-sided native valve endocarditis usually is caused by Streptococcus viridans, S. aureus, and Enterococcus. The vast majority of right-sided endocarditis is caused by S. aureus.

▶Valve replacement usually is necessary for persistent infection, recur-rent embolization, or when medical therapy is ineffective, for example, in cases of large vegetations as seen in fungal endocarditis.

▶Culture-negative endocarditis is usually caused by prior administration of antibiotics before obtaining blood cultures or by infection with fungi or fastidious organisms, such as the HACEK group.

REFERENCES

Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications. Circulation. 2005;111:3167-3184.

Fred HL. Little black bags, ophthalmoscopy, and the Roth spot. Texas Heart Inst J. 2013;40(2):115-116.

Houpikian P, Raoult D. Blood culture negative endocarditis in a reference center: etiologic diagnosis of 348 cases. Medicine. 2005;84:162-173.

Karchmer AW. Infective endocarditis. In: Jameson JL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 20th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2018:1052-1063.

Mylonakis E, Calderwood SB. Infective endocarditis in adults. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1318-1330.

Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis. Guidelines from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;116(15):1736-1754.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.