Pericardial Effusion/Tamponade Caused by Malignancy Case File

Eugene C. Toy, MD, Gabriel M. Aisenberg, MD

Case 11

A 42-year-old man presents complaining of 2 days of worsening chest pain and dyspnea. Six weeks ago, he was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma with lymphadenopathy of the mediastinum and was treated with mediastinal radiation therapy. His most recent treatment was 1 week ago. He has no other medical or surgical history and takes no medications. His chest pain is constant and unrelated to activity. He becomes short of breath with minimal exertion. He is afebrile; heart rate is 115 beats per minute (bpm) with a thready pulse, respiratory rate is 22 breaths per minute, and blood pressure is 108/86 mm Hg. Systolic blood pressure drops to 86 mm Hg on inspiration. He appears uncomfortable and is diaphoretic. His jugular veins are distended to the angle of the jaw, and his chest is clear to auscultation. He is tachycardic, his heart sounds are faint, and no extra sounds are appreciated. The chest x-ray is shown in Figure 11–1.

Figure 11–1. Chest x-ray. (Courtesy of Dr. Jorge Albin.)

▶ What is the most likely diagnosis?

▶ What is your next step in therapy?

ANSWERS TO CASE 11:

Pericardial Effusion/Tamponade Caused by Malignancy

Summary: A 42-year-old man presents with

- A thoracic malignancy and history of radiotherapy to the mediastinum

- Complaints of chest pain and dyspnea

- Jugular venous distention, distant cardiac sounds, and pulsus paradoxus on examination

- Cardiac enlargement on chest x-ray (which could represent cardiomegaly or pericardial effusion)

Most likely diagnosis: Pericardial effusion causing cardiac tamponade.

Next therapeutic step: Urgent pericardiocentesis or surgical pericardial window.

ANALYSIS

Objectives

- Recognize pericardial tamponade and pulsus paradoxus. (EPA 1, 10)

- Identify the features of cardiac tamponade, constrictive pericarditis, and restrictive cardiomyopathy and how to distinguish among them. (EPA 1, 3)

- Understand the treatment of each of these conditions. (EPA 4, 10)

- Describe the potential cardiac complications of thoracic malignancies and radiation therapy. (EPA 4, 12)

Considerations

A patient with thoracic malignancy and history of radiation therapy, like this patient, is at risk for diseases of the pericardium and myocardium. The jugular venous distention, distant heart sounds, and pulsus paradoxus all are suggestive of cardiac tamponade. The major diagnostic considerations in this case, each with very different treatment, are pericardial effusion causing cardiac tamponade, constrictive pericarditis, and restrictive cardiomyopathy. All of these conditions can impede diastolic filling of the heart and lead to cardiovascular compromise. Urgent differentiation among these conditions is required because the treatment is very different, and the consequences of mistreating these diseases can be immediately fatal. Clinically, the patient’s fall in systolic blood pressure with inspiration (pulsus paradoxus) is suggestive of cardiac tamponade, which would be treated with evacuation of the pericardial fluid via pericardiocentesis.

APPROACH TO:

Cardiac Tamponade

DEFINITIONS

CARDIAC TAMPONADE: Increased pressure within the pericardial space caused by an accumulating effusion, which compresses the heart and impedes diastolic filling.

PERICARDIAL EFFUSION: Fluid that fills the pericardial space, which may be due to infection, hemorrhage, or malignancy. A rapidly accumulating effusion may lead to cardiac compromise.

CLINICAL APPROACH

Pathophysiology

Cardiac tamponade refers to increased pressure within the pericardial space caused by an accumulating effusion, which compresses the heart and impedes diastolic filling. Because the heart can only pump out during systole what it receives during diastole, severe restriction of diastolic filling leads to a marked decrease in cardiac output, culminating in hypotension, cardiovascular collapse, and death. If pericardial fluid accumulates slowly, the sac may dilate and hold up to 2000 mL (producing notable cardiomegaly on chest x-ray) before causing diastolic impairment. If the fluid accumulates rapidly, as in a hemopericardium caused by trauma or surgery, as little as 200 mL can produce tamponade.

Clinical Presentation

The classic description of Beck’s triad (hypotension, elevated jugular venous pressure, and small, quiet heart) is a description of acute tamponade with rapid accumulation of fluid, as in the cases of cardiac trauma or ventricular rupture. If the fluid accumulates slowly, the clinical picture may look more like heart failure, with cardiomegaly on chest x-ray (although there should be no pulmonary edema), dyspnea, elevated jugular pressure, hepatomegaly, and peripheral edema. A high index of suspicion is required: Cardiac tamponade should be considered in any patient with hypotension and elevated jugular venous pressure.

The most important physical sign to look for in cardiac tamponade is pulsus paradoxus. This refers to a drop in systolic blood pressure of more than 10 mm Hg during inspiration. Although called “paradoxical,” this drop in systolic blood pressure is not contrary to the normal physiologic variation with respiration; it is an exaggeration of the normal small drop in systolic pressure during inspiration. Although not a specific sign of tamponade (ie, it is often seen in patients with disturbed intrathoracic pressures during respiration, eg, those with obstructive lung disease), pulsus paradoxus is fairly sensitive for hemodynamically significant tamponade.

To test for this, one must use a manual blood pressure cuff that is inflated above systolic pressure and deflated very slowly until the first Korotkoff sound is heard during expiration and then, finally, during both phases of respiration. The difference between these two pressure readings is the pulsus paradoxus. When the pulsus paradoxus is severe, it may be detected by palpation as a diminution or disappearance of peripheral pulses during inspiration.

Treatment

Acute treatment of cardiac tamponade consists of relief of the pericardial pressure, by either percutaneous pericardiocentesis (possibly echocardiographically guided) or a surgical approach. The choice between percutaneous versus surgical effusion relief is dependent on clinical and institutional expertise. Resection of the diseased pericardium is the definitive treatment of constrictive pericarditis. There is no effective treatment for restrictive cardiomyopathy. Any patient with evidence of cardiovascular compromise (ie, cardiac tamponade) should have immediate drainage of effusion in the pericardium. If there is no evidence of hemodynamic collapse, then urgent drainage is not necessary. Patients with large effusions who are hemodynamically stable may require close monitoring, serial echocardiography, and careful volume status regulation with management directed to treat the underlying cause of the effusion. Beyond its described therapeutic benefit, pericardiocentesis can offer diagnostic value when the presumed etiology cannot be established.

Complications

Constrictive pericarditis is a complication of a prior episode of acute or chronic fibrinous pericarditis. The inflammation with resultant granulation tissue forms a thickened fibrotic adherent sac that gradually contracts, encasing the heart and impairing diastolic filling. In the past, tuberculosis was the most common cause of this problem, but now that is a rare cause in the United States. Currently, this is most commonly caused by radiation therapy, cardiac surgery, or any cause of acute pericarditis, such as viral infection, uremia, or malignancy. The pathophysiology of constrictive pericarditis is similar to that of cardiac tamponade in the restricted ability of the ventricles to fill during diastole because of the thickened noncompliant pericardium.

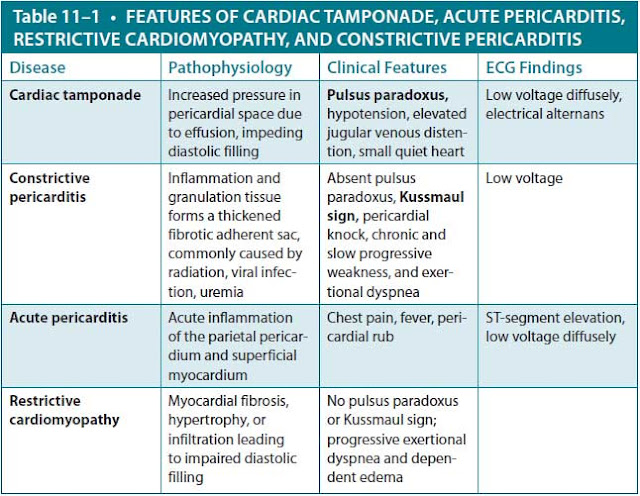

Because the process is chronic, patients with constrictive pericarditis generally do not present with acute hemodynamic collapse but rather with chronic and slowly progressive weakness, fatigue, and exertional dyspnea. Patients commonly have what appears to be right-sided heart failure, that is, chronic lower extremity edema, hepatomegaly, and ascites. Like patients with tamponade, they have elevated jugular venous pressures, but pulsus paradoxus usually is absent. Examination of neck veins shows an increase in jugular venous pressure during inspiration, termed the Kussmaul sign. This is easy to see because it is the opposite of the normal fall in pressure as a person inspires. Normally, the negative intrathoracic pressure generated by inspiration increases blood flow into the heart, but because of the severe diastolic restriction, the blood cannot enter the right atrium or ventricle, so it fills the jugular vein. Another physical finding characteristic of constrictive pericarditis is a pericardial knock, which is a high-pitched, early diastolic sound occurring just after aortic valve closure. Chest radiography frequently shows cardiomegaly and a calcified pericardium. Table 11–1 compares features of cardiac tamponade, acute pericarditis, restrictive cardiomyopathy, and constrictive pericarditis.

Restrictive cardiomyopathy, like the previous diagnoses, is primarily a problem of impaired diastolic filling, usually with preserved systolic function. This is a relatively uncommon problem in the Western world. The most common causes are amyloidosis, an infiltrative disease of the elderly, in which an abnormal fibrillar amyloid protein is deposited in heart muscle, or fibrosis of the myocardium following radiation therapy or open-heart surgery. In Africa, restrictive cardiomyopathy is much more common because of a process called endomyocardial fibrosis, characterized by fibrosis of the endocardium along with fever and marked eosinophilia, accounting for up to 25% of deaths due to heart disease.

Clinically, it may be very difficult to distinguish restrictive cardiomyopathy from constrictive pericarditis, and various echocardiographic criteria have been proposed to try to distinguish between them. In addition, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be very useful to visualize or exclude the presence of the thickened pericardium typical of constrictive pericarditis and absence in restrictive cardiomyopathy. Kussmaul sign can be seen in both restrictive cardiomyopathy and constrictive pericarditis. Nevertheless, it may be necessary to obtain an endomyocardial biopsy to make the diagnosis. Differentiation between the two is essential because constrictive pericarditis is a potentially curable disease, whereas very little effective therapy is available for either the underlying conditions or the cardiac failure of restrictive cardiomyopathy.

CASE CORRELATION

- See also Case 3 (Acute Coronary Syndrome), Case 4 (Heart Failure Due to Critical Aortic Stenosis), Case 8 (Atrial Fibrillation/Mitral Stenosis), and Case 10 (Acute Pericarditis Caused by Systemic Lupus Erythematosus).

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

11.1 A 35-year-old woman is being seen for shortness of breath of 2 weeks’ duration. She denies a history of asthma, smoking, or cough. On examination, her heart rate is 100 bpm, blood pressure is 90/60 mm Hg, and respiratory rate is 20 breaths per min. Her jugular venous pulse was noted at rest to be 2 cm above the sternal notch, increasing to 6 cm above the sternal notch with deep inspiration. Which of the following conditions does she most likely have?

A. Constrictive pericarditis

B. Cardiac tamponade

C. Dilated cardiomyopathy

D. Diabetic ketoacidosis

11.2 A 53-year-old man has been undergoing dialysis for end-stage renal disease due to long-standing diabetes mellitus. He is being seen in the emergency center for progressive dyspnea on exertion. On examination, he is found to have a heart rate of 105 bpm, blood pressure of 90/60 mm Hg, and respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute. After examination, the clinician suspects cardiac tamponade. Which of the following is the most sensitive finding in this condition?

A. Disappearance of radial pulse during inspiration

B. Drop in systolic blood pressure more than 10 mm Hg during inspiration

C. Rise in heart rate more than 20 bpm during inspiration

D. Distant heart sounds

11.3 A 35-year-old man is brought into the emergency department after a knife injury to the chest. He is noted to be hypotensive with a blood pressure of 80/40 mm Hg and an elevated jugular venous pulse. Bedside ultrasound examination confirms a large cardiac effusion. While awaiting pericardiocentesis, which of the following is the most important intervention for the patient to receive?

A. Diuresis with furosemide

B. Intravenous fluids

C. Nitrates to lower venous congestion

D. Morphine to relieve dyspnea

11.4 Which of the following is most likely to cause restrictive cardiomyopathy?

A. Endomyocardial fibrosis

B. Viral myocarditis

C. Beriberi (thiamine deficiency)

D. Doxorubicin therapy

ANSWERS

11.1 A. This patient has shortness of breath and an increase in the jugular venous pulse with deep inspiration, which is called the Kussmaul sign. This increase in neck veins with inspiration is seen with constrictive pericarditis (and restrictive cardiomyopathy) and is due to the impaired diastolic dysfunction and inability of blood to enter the right ventricle. Normally, the jugular venous pulse decreases with inspiration since the negative intrathoracic pressure “pulls” the blood into the chest. The other answer choices (B, cardiac tamponade; C, dilated cardiomyopathy; and D, diabetic ketoacidosis) are not associated with Kussmaul sign. Cardiac tamponade is associated with a distended jugular venous pulse at baseline.

11.2 B. Cardiac tamponade is caused by an effusion in the pericardial space that does not allow for cardiac filling. This patient likely has a pericardial effusion due to uremia. Pulsus paradoxus is a sensitive yet nonspecific sign for cardiac tamponade. Other clinical features include hypotension, elevated jugular venous distention, and soft heart sounds. Answer A (disappearance of radial pulse during inspiration) is possible in severe tamponade but not common. Answer C (rise in heart rate more than 20 bpm during inspiration) is not seen in tamponade. Answer D (distant heart sounds) is found in pericardial effusion with or without tamponade.

11.3 B. Patients with cardiac tamponade are preload dependent; therefore, diuretics (answer A), nitrates (answer C), or morphine (answer D) may cause them to become hypotensive. In contrast, volume expansion with intravenous fluids helps maintain intravascular volume and cardiac output.

11.4 A. Endomyocardial fibrosis is an etiology of restrictive cardiomyopathy. It is common in developing countries and is associated with eosinophilia. The other disease processes mentioned (answer B, viral myocarditis; answer C, beriberi; and answer D, doxorubicin therapy) are causes of dilated cardiomyopathy.

CLINICAL PEARLS

▶ Elevated jugular venous pressure and pulsus paradoxus are features of cardiac tamponade.

▶ Kussmaul sign and right-sided heart failure are features of constrictive cardiomyopathy, but pulsus paradoxus is not.

▶ Cardiac tamponade requires urgent treatment by pericardiocentesis or a pericardial drainage.

▶ Constrictive pericarditis may show calcifications of the pericardium on chest x-ray or thickened pericardium on echocardiography. Definitive therapy is resection of the pericardium.

▶ Restrictive cardiomyopathy is most often caused by amyloidosis or radia-tion therapy in the western hemisphere. There is no effective therapy.

REFERENCES

Bertog SC, Thambidorai SK, Parakh K, et al. Constrictive pericarditis: etiology and cause-specific survival after pericardiectomy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1445-1452.

McGregor M. Pulsus paradoxus. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:480-482.

Spodick DH. Acute cardiac tamponade. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:684-690.

Wynne J, Braunwald E. Cardiomyopathy and myocarditis. In: Jameson JL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 20th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2018:1951-1970.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.