Colitis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Case File

Eugene C. Toy, MD, Gabriel M. Aisenberg, MD

Case 21

A 28-year-old man comes to the emergency center complaining of abdominal pain and diarrhea for 2 days. He claims to defecate frequently, usually 10 to 12 times per day, consisting of small-volume stools. Blood and mucus are occasionally visualized in the stool. These episodes are preceded by a sudden urge to defecate. The abdominal pain is crampy, diffuse, moderately severe, and not relieved with defecation. In the past 6 to 8 months, he has experienced similar episodes of abdominal pain that were milder, resolved within 24 to 48 hours, and were associated with loose, mucoid, bloody stools. He has no other medical history and takes no medications. He has neither traveled out of the United States nor had contact with anyone experiencing similar symptoms. He works as an accountant and does not smoke or drink alcohol. The patient denies any family history of gastrointestinal (GI) problems.

On examination, his temperature is 99 °F, heart rate (HR) is 98 beats per minute (bpm), and blood pressure (BP) is 118/74 mm Hg. He appears uncomfortable and is lying still on the stretcher. His sclerae are anicteric, and his oral mucosa is pink without ulceration. His chest is clear to auscultation, and his heart rhythm is regular, without murmurs. His abdomen is soft and mildly distended with hypoactive bowel sounds. There is a mild diffuse tenderness upon palpation, but no guarding or rebound tenderness is elicited.

Laboratory studies are significant for a white blood cell (WBC) count of 15,800/mm3 with 82% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, hemoglobin 10.3 g/dL, and platelet count 754,000/mm3. The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) assay is negative. Renal function and liver function tests are normal. A plain film radiograph of the abdomen shows a mildly dilated, air-filled colon 4.5 cm in diameter without air-fluid levels or evidence of pneumoperitoneum.

▶ What is the most likely diagnosis?

▶ What complications are associated with this disease?

▶ What is the next best step in establishing the diagnosis?

▶ What is the most appropriate treatment at this time?

ANSWERS TO CASE 21:

Colitis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Summary: A 28-year-old man presents with

- Chronic, “crampy” abdominal pain that is not relieved with defecation

- Tenesmus

- Bloody/mucoid stools

- Colon distention, visualized on abdominal x-ray

- No history of foreign travel

Most likely diagnosis: Colitis, secondary to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD; eg, ulcerative colitis [UC], Crohn disease [CD]) because the patient is young, experiencing crampy abdominal pain not relieved with defecation, bloody/mucoid stools, and an increase in stool frequency and urgency.

Associated complications: Complications associated with IBD are toxic megacolon, bowel perforation with peritonitis, abscesses, and fistula formation (eg, enterovesical fistula).

Next step to confirm diagnosis: After obtaining stool samples to exclude infection, colonoscopy would be appropriate to confirm the diagnosis of IBD.

Most appropriate treatment: Admit the patient to the hospital and begin treatment with corticosteroids (eg, budesonide, prednisone).

- Describe the typical presentation of IBD. (EPA 1, 2)

- Recognize the differences between CD and UC. (EPA 2, 3)

- Describe the treatment of IBD. (EPA 4)

Considerations

Although the likelihood in this patient is low, infection must be excluded. Common organisms that cause colitis are Entamoeba histolytica, Salmonella, Shigella, Escherichia coli, Campylobacter, and Clostridium difficile, which can occur even in the absence of prior antibiotic exposure. The main consideration in this case would be IBD versus infectious colitis. The absence of travel history and sick contacts and the chronicity of the illness all point away from infection.

This patient does not appear to have any life-threatening complications of colitis, such as a perforation or toxic megacolon. However, close monitoring is imperative, and surgical consultation may be helpful in the event that such complications arise during hospitalization.

APPROACH TO:

Colitis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease

DEFINITIONS

COLITIS: Inflammation of the colon, which may be due to infectious, autoimmune, ischemic, or idiopathic causes.

CROHN DISEASE: Inflammatory disease of the bowel that involves the full thickness of the bowel wall and can affect the intestines anywhere from esophagus to anus, although the ileum is most commonly affected.

INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE: An autoimmune condition characterized by inflammation of the intestinal tract; may be further subdivided into CD or UC.

TENESMUS: Feeling an urge to defecate.

ULCERATIVE COLITIS: Inflammatory disease affecting the mucosa of the bowel, principally the large bowel.

CLINICAL APPROACH TO COLITIS

Pathophysiology

The differential diagnosis for colitis includes ischemic colitis, infectious colitis (C. difficile, E. coli, Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter), radiation colitis, and IBD (CD vs UC).

Ischemic colitis (eg, mesenteric colitis) usually presents in people older than 50 years with known atherosclerotic vascular disease (eg, peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease). The pain is usually acute, commonly after a meal (“intestinal angina”) and not associated with fevers.

Patients with infectious colitis usually present with fever, leukocytosis, abdominal pain, and diarrhea, which may be categorized as either invasive diarrhea (“dysentery”) or watery diarrhea. The stools associated with dysentery are hemorrhagic, appearing grossly bloody (hematochezia) or black/tar-like (melena). Infectious colitis associated with profuse watery diarrhea is usually indicative of C. difficile infection and presents in the setting of antibiotic use. The initial workup for infectious colitis includes stabilizing the patient with normal saline if hypovolemic shock is present (systolic BP < 90 mm Hg), obtaining a stool culture, and sampling for bacterial toxins (Shiga toxin, C. difficile toxins).

Radiation enteritis presents as abdominal pain associated with nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, and lower GI bleeding, 3 or more months after completing radiation therapy. Imaging studies, such as abdominal computed tomography, or endoscopic studies (eg, colonoscopy) would demonstrate segmental bowel inflammation in regions of a known radiation field.

Treatment

Antimicrobial therapy (eg, azithromycin, ciprofloxacin) is recommended for treatment of severe dysentery caused by Campylobacter and entero-hemorrhagic or entero-toxigenic E. coli. Antibiotic therapy for the treatment of Shiga toxin–producing strains of E. coli remain controversial. C. difficile infection requires treatment with oral vancomycin. Although antimotility drugs (eg, loperamide) may improve symptoms of watery diarrhea, these agents should be avoided in cases of bloody diarrhea. Risk factors for infectious colitis include recent history of foreign travel (E. histolytica), consumption of raw/undercooked meat (Shigella, E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella, Campylobacter), and antibiotic use (C. difficile).

CLINICAL APPROACH TO INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

Epidemiology

IBD is an autoimmune condition characterized by chronic inflammation of the intestinal tract. Disease incidence is bimodal, most commonly presenting in young patients between the ages of 15 and 35, with a second peak between the ages of 60 and 70. Although patients may initially complain of GI symptoms (eg, chronic abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea), systemic symptoms may also be present, such as fever, weight loss, and anemia, either due to iron deficiency (chronic GI blood loss) or anemia of chronic disease. IBD encompasses two major disorders, UC and CD, each demonstrating their own clinical and pathologic characteristics, yet with substantial overlap.

Pathophysiology

UC is the most common subtype of IBD and is a chronic inflammatory condition that is limited to the mucosal and submucosal surface of the colon. The exact mechanism for developing UC remains unclear but is thought to be caused by a dysregulated immune response to a microbial pathogen in the intestine, resulting in colonic inflammation. The inflammation associated with UC always begins at the rectum, is circumferential, and extends proximally, involving other portions of the colon in a continuous pattern. Different terms may be used to describe the degree of colonic extension. For example, ulcerative proctitis refers to inflammation limited to the rectum. Ulcerative proctosigmoiditis refers to inflammation limited to the rectum and sigmoid colon. Left-sided colitis refers to inflammation extending proximally from the rectum to the splenic flexure. Symptoms of UC progress gradually, consisting of bloody diarrhea, increased stool frequency, urgency, tenesmus, and left lower quadrant (LLQ) abdominal pain due to rectum/colonic involvement. Abdominal imaging is not required for the diagnosis of UC. However, barium x-rays may show a “lead pipe colon” due to colonic inflammation and edema. Colonoscopy with visualization of ulcers is the gold standard for diagnosing UC. Biopsy of these lesions demonstrates crypt atrophy with polymorphonuclear cell infiltration (“crypt abscesses”).

CD is the other subtype of IBD and is characterized by transmural inflammation, which may arise at any portion of the GI tract, from the mouth to the perianal area. Unlike UC, the inflammation in CD is noncontinuous and most

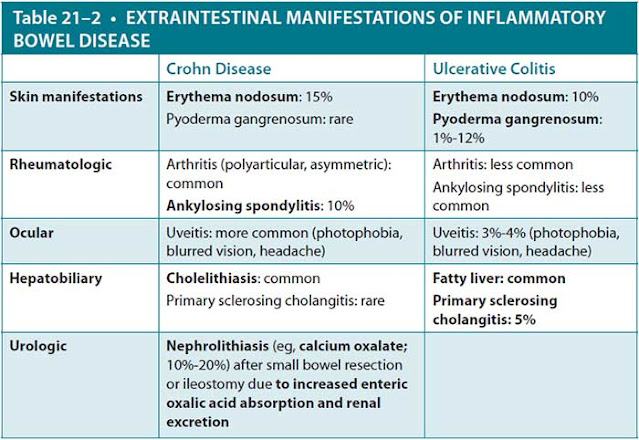

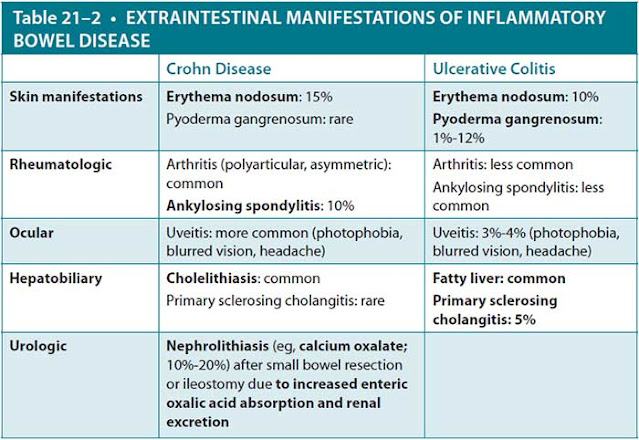

commonly affects the terminal ileum, resulting in right lower quadrant (RLQ) abdominal pain. Other symptoms associated with CD are fever, weight loss, and prolonged diarrhea with or without gross bleeding. Like UC, abdominal imaging is not required to diagnose CD. However, the “string sign” is a classic finding on barium x-rays, correlating to strictures in the lower GI tract. Endoscopic evaluation with visualization of GI inflammation is the gold standard for diagnosing CD. Grossly, the intestinal lumen classically reveals “cobblestoning” of the mucosa, with biopsy of these lesions demonstrating noncaseating granulomas. Tables 21–1 and 21–2 summarize features seen in UC and CD.

Treatment

The treatment for UC is aimed at reducing colonic inflammation and varies depending on disease severity. For mild-to-moderate inflammation, sulfasalazine or other 5-aminosalicylic acid (ASA) compounds, such as mesalamine, are used. Corticosteroids (oral, rectal, or intravenous) are used for the initial treatment of severe UC flares and are gradually tapered once remission is achieved to avoid side effects. Immune modulators (eg, 6-mercaptopurine, azathioprine, methotrexate, infliximab) are used for refractory cases, but they may reactivate latent infections (eg, tuberculosis). Since inflammation is limited to the colon in UC, total colectomy is curative but is reserved for medically intractable disease, management of acute complications, or treatment of colorectal cancer/dysplasia.

Treatment of CD is similar to that of UC, but it does have some major differences. Like UC, remission of an acute CD flare is also achieved with corticosteroids (eg, budesonide, prednisone), which are tapered once remission is achieved. A thiopurine (eg, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine) or biologic agent (eg, infliximab) may be added to maintain remission. However, unlike UC, treatment of CD with colectomy is not curative since these lesions may occur at any portion of the GI tract and are not limited to the colon.

Complications

Ulcerative Colitis. Ulcerative colitis is associated with both acute and chronic complications. Acute complications include severe hemorrhage, fulminant colitis/toxic megacolon, and colonic perforation. Patients with severe bleeding may present with hemorrhagic shock (systolic BP < 90 mm Hg) and have anemia. Symptoms associated with fulminant colitis include profound increase in stool frequency (> 10 stools/d), abdominal pain, distention, and severe toxic symptoms, such as fever, leukocytosis, tachycardia, hypotension, and altered mental status. These patients are at increased risk for developing toxic megacolon, which is characterized by colonic diameter > 6 cm or cecal diameter > 9 cm in the presence of systemic toxicity. Colonic perforation with peritonitis is the most severe complication of UC, usually resulting from untreated toxic megacolon, and it is associated with 50% mortality in patients with UC. Management involves providing prompt intravenous fluids and nasogastric decompression, ensuring the patient receives nothing by mouth (NPO), and referring for a surgical evaluation for colectomy. Broad-spectrum antibiotics and systemic corticosteroids are also administered to reduce inflammation.

Patients with UC also have a marked increase in the incidence of colon cancer compared to the general population. The risk of cancer increases over time and is related to disease duration and extent. Annual or biennial colonoscopy is advised in patients with UC, beginning 8 years after diagnosis, and random biopsies should be sent for evaluation. If colon cancer or dysplasia is found, a colectomy is recommended.

Crohn Disease. Complications associated with CD are fistula formation, perianal disease, and malabsorption. Chronic transmural inflammation may cause a sinus tract to gradually form within the bowel wall, which may predispose to fistula formation if the sinus tract penetrates through the serosa and connects to another epithelial-lined organ. Clinical manifestations of fistula formation vary depending on organ involvement. For example, fistulas connecting the bowel to bladder (enterovesical fistulas) present with recurrent urinary tract infections and pneumaturia. Enterovaginal fistulas may present with gas or feces emanating from the vaginal vault.

Other complications associated with CD include perianal disease and malabsorption. More than one-third of patients with CD complain of perianal disease. Symptoms may include large perianal skin tags, fissures, or abscesses, which may evolve into fistulas. Terminal ileum involvement may cause malabsorption of bile salts, resulting in deficiency of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K), and/or malabsorption of vitamin B12, corresponding to megaloblastic anemia with possibly subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord.

CASE CORRELATION

- See also Case 22 (Acute Diverticulitis) and Case 23 (Chronic Diarrhea).

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

21.1 A 32-year-old woman is being seen in the office for follow-up of her systemic inflammatory condition. She has a history of chronic diarrhea and gallstones. Today, she complains of 3 days’ duration of “brown, foul-smelling discharge” leaking from her vagina. The clinician believes that the vaginal condition is related to her primary disease. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Crohn disease

B. Ulcerative colitis

C. Systemic lupus erythematosus

D. Sarcoidosis

21.2 A 45-year-old man with a history of UC is admitted to the hospital with 2 to 3 weeks of right upper quadrant abdominal pain, jaundice, and pruritus. He states that he has not had these symptoms previously. He has no fever and has a normal WBC count. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) shows stricture formation of intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts with intervening segments of normal and dilated ducts. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC)

B. Cholangiocarcinoma

C. Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)

D. Choledocholithiasis with resultant biliary strictures

21.3 A 25-year-old man is hospitalized for an exacerbation of UC. He complains of abdominal pain and fever. On examination, he is found to have a temperature of 101 °F, HR 110 bpm, and BP 100/60 mm Hg. His abdomen is distended. On abdominal x-ray, he is noted to have bowel distention with a transverse colonic dilation of 7 cm. Which of the following is the best next step?

A. 5-ASA

B. Oral steroids

C. Intravenous antibiotics and prompt surgical consultation

D. Infliximab

21.4 A 35-year-old woman complains of chronic crampy abdominal pain, intermittent constipation, and diarrhea. She denies weight loss or GI bleeding. Her abdominal pain is usually relieved with defection. Colonoscopy and upper endoscopy with biopsies are normal, and stool cultures are negative. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Infectious colitis

B. Irritable bowel syndrome

C. Crohn disease

D. Ulcerative colitis

ANSWERS

21.1 A. This patient likely has an enterovaginal fistula based on the history of stool leaking into the vaginal area. Fistulas (eg, rectovaginal fistulas) are common with CD because of transmural inflammation. Fistulas can occur between bowel, between the bowel and other organs (bladder, vagina), or between the bowel and skin (enterocutaneous). In contrast, the mucosal inflammation seen in UC (answer B) is not associated with fistulas. Gallstones are common in patients with CD due to bile salt malabsorption, which is necessary to increase cholesterol solubility in bile. Systemic lupus erythematosus (answer C) is more commonly associated with joint pain, alopecia, serositis, rash, anemia, central nervous system findings, and renal dysfunction. Sarcoidosis (answer D) is associated with pulmonary findings such as shortness of breath and cough, neurologic manifestations, and systemic findings (fever, weight loss). Neither systemic lupus erythematosus nor sarcoidosis is associated with fistulas.

21.2 C. The ERCP shows the typical appearance for PSC, which is associated with IBD (predominantly UC) in 75% of cases. PSC is more common in men. Antibodies against perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA) are also common. Stone-induced strictures such as those due to choledocholithiasis (answer D) are extrahepatic and unifocal. Cholangiocarcinoma (answer B) is less common but may develop in 10% of patients with PSC. PBC (answer A) is an autoimmune disorder characterized by destruction of intrahepatic bile ducts, presenting with jaundice and extensive pruritus secondary to cholestasis. PBC is more common in women and is associated with antimitochondrial antibodies.

21.3 C. Colonic dilation greater than or equal to 6 cm with signs of systemic toxicity (ie, fever) makes the diagnosis of toxic megacolon more likely. With toxic megacolon, antibiotics and surgical intervention are often necessary and lifesaving. Medical therapy includes bowel rest with total parenteral nutrition, intravenous steroids, and antibiotics. Sulfasalazine and 5-ASA compounds (answer A) are not recommended for the treatment of toxic megacolon. The other answer choices are medical therapy (answer B, oral steroids and answer D, infliximab) and would only delay addressing the possible emergency.

21.4 B. Irritable bowel syndrome is characterized by intermittent diarrhea and/or constipation and crampy abdominal pain often relieved with defecation. Weight loss, fecal blood, and intestinal biopsies are negative. It is a diagnosis of exclusion once other conditions, such as IBD and parasitic infection (eg, giardiasis), have been excluded. The other diseases (answer A, infectious colitis; answer C, Crohn disease; answer D, ulcerative colitis) are associated with fever, weight loss and systemic symptoms.

CLINICAL PEARLS

▶ Ulcerative colitis always involves the rectum and may extend proximally in a continuous distribution.

▶ Crohn disease most commonly involves the distal ileum, but it may involve any portion of the GI tract in a noncontinuous (“skip lesions”) distribution.

▶ Crohn disease is often complicated by fistula formation and malabsorp-tion of fat-soluble vitamins and vitamin B12.

▶ Toxic megacolon is associated with UC and characterized by dilation of the colon with symptoms of systemic toxicity; failure to improve with medical therapy may require surgical intervention.

▶ Ulcerative colitis is associated with increased risk of colon cancer; the risk increases with duration and extent of disease.

▶ Both UC and CD can be associated with extraintestinal manifestations, such as uveitis, erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, arthritis, and PSC.

REFERENCES

Banerjee S, Peppercorn MA. Inflammatory bowel disease. Medical therapy of specific clinical presentations. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002;341:147-166.

Danese S, Fiocchi C. Medical progress: ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1713-1725.

Friedman S, Blumberg RS. Inflammatory bowel disease. In: Jameson J, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 20th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2018.

Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2018;390:2769-2778.

Peppercorn MA, Kane SV. Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and prognosis of ulcerative colitis in adults. Rutgeerts P, ed. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2019. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-diagnosis-and-prognosis-of-ulcerative-colitis-in-adults. Accessed July 24, 2019.

Regueiro M, Hashash JA. Overview of the medical management of mild (low risk) Crohn disease in adults. Rutgeerts P, ed. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2019. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-medical-management-of-high-risk-adult-patients-with-moderate-to-severe-crohn-disease. Accessed July 24, 2019.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.