Pancreatitis/Gallstones Case File

Eugene C. Toy, MD, Gabriel M. Aisenberg, MD

Case 25

A 42-year-old woman presents to the emergency department complaining of 24 hours of severe, steady epigastric abdominal pain radiating to her back with several episodes of nausea and vomiting. She has experienced similar painful episodes in the past, usually in the evening following heavy meals, but the prior episodes always resolved spontaneously within an hour or two. This time the pain did not improve, so she sought medical attention. She has no medical history and takes no medications. She is married, has three children, and does not drink alcohol or smoke cigarettes.

On examination, she is afebrile with tachycardia of 104 beats per minute (bpm), a blood pressure of 115/74 mm Hg, and shallow respirations at a rate of 22 breaths/min. She is moving uncomfortably on the stretcher. Her skin is warm and diaphoretic, and she has scleral icterus. Her abdomen is soft, mildly distended with marked right upper quadrant (RUQ) and epigastric tenderness to palpation, hypoactive bowel sounds, and no palpable masses or organomegaly. Her stool is negative for occult blood. Laboratory studies are significant for an elevated total bilirubin (9.2 g/dL) with a direct fraction of 4.8 g/dL, alkaline phosphatase 285 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 78 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 92 IU/L, and elevated serum lipase level. Her leukocyte count is 16,500/mm3 with 82% polymorphonuclear cells and 16% lymphocytes. Serum electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and creatinine are normal. A plain film of the abdomen shows a nonspecific gas pattern and no pneumoperitoneum, and chest x-ray is normal.

▶ What is the most likely diagnosis?

▶ What is the most likely underlying etiology?

▶ What is your next diagnostic step?

▶ What is the most important immediate therapeutic step?

ANSWERS TO CASE 25:

Pancreatitis/Gallstones

Summary: A 42-year-old woman presents with

A prior history consistent with symptomatic cholelithiasis (gallstones)

Epigastric pain and nausea for 24 hours

Hyperbilirubinemia and an elevated alkaline phosphatase level

Elevated serum lipase levels

Most likely diagnosis: Acute pancreatitis is the most likely diagnosis based on her history of persistent epigastric pain radiating to her back with associated nausea and vomiting.

Most likely etiology: Choledocholithiasis (common bile duct stone) based on the hyperbilirubinemia.

Next diagnostic step: RUQ and abdominal ultrasonography and assessment for complications of pancreatitis, such as electrolyte, bicarbonate, calcium, and glucose levels.

Most important immediate therapeutic step: Intravenous fluid hydration to support the blood pressure and replace electrolytes.

- Describe the causes, clinical features, and prognostic factors in acute pancreatitis. (EPA 1, 2)

- List the principles of treatment and complications of acute pancreatitis. (EPA 4, 10)

- Recognize the complications of gallstones. (EPA 10, 12)

- Understand the medical treatment of a patient with biliary sepsis and the indications for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or surgical intervention. (EPA 4, 10)

Considerations

This 42-year-old woman complained of intermittent episodes of short duration of mild RUQ abdominal pain with heavy meals in the past. This is very consistent with biliary colic. However, this episode is different in severity and location of pain (now radiating straight to her back and accompanied by nausea and vomiting). The elevated lipase level confirms the clinical impression of acute pancreatitis likely caused by a stone in the common bile duct. Biliary obstruction is suggested by the elevated bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels. She is moderately ill but is hemodynamically stable and has only one prognostic feature to predict mortality.

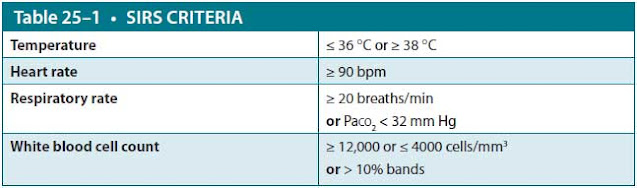

Abbreviation: Paco2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide.

Data from Ranson JH. Etiological and prognostic factors in human acute pancreatitis: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 1982;77:633.

She meets criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and should be monitored closely for signs of clinical deterioration (Table 25–1).

APPROACH TO:

Acute Pancreatitis and Cholelithiasis

DEFINITIONS

ACUTE PANCREATITIS: An inflammatory process in which pancreatic enzymes are activated and cause autodigestion of the pancreas.

PANCREATIC PSEUDOCYST: Fluid collection within the pancreas not lined by epithelial cells, appearing several days after some cases of acute pancreatitis and often associated with chronic pancreatitis.

CLINICAL APPROACH TO ACUTE PANCREATITIS

Pathophysiology

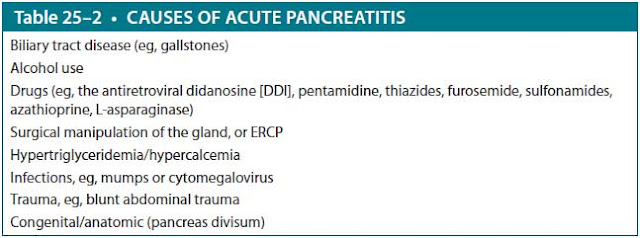

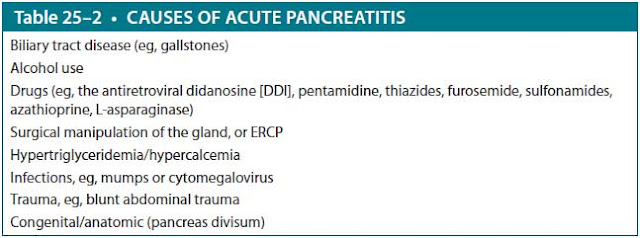

Acute pancreatitis can be caused by many conditions, although gallstones and alcohol are implicated in up to two-thirds of cases. The passage of gallstones into the common bile duct is the most common cause and is responsible for approximately 40% to 70% of cases. Alcohol use is the next most common cause (25%-35% of cases in the United States), with episodes often precipitated by binge drinking. Hypertriglyceridemia is another common cause (1%-14% of cases) and occurs when serum triglyceride levels are more than 1000 mg/dL, as is seen in patients with familial dyslipidemias or diabetes (etiologies are given in Table 25–2). Acute pancreatitis can also be induced by ERCP, occurring after 5% to 10% of such procedures. Less common etiologies include genetic predisposition, medication, infections, hypercalcemia, toxins, vascular disease, or anatomic/physiologic anomalies of the pancreas. When patients appear to have “idiopathic” pancreatitis, that is, no gallstones are seen on ultrasonography and no other predisposing factor can be

found, biliary tract disease is still the most likely cause, either biliary sludge (microlithiasis) or sphincter of Oddi dysfunction.

Epigastric pain and/or RUQ pain can have a variety of etiologies. Other diagnoses that may be considered during the workup of acute pancreatitis include peptic ulcer disease, bowel perforation, intestinal obstruction, mesenteric ischemia, diabetic ketoacidosis, or hepatitis. Many additional diagnoses that should be considered are directly related to gallstone production, including biliary colic, choledocholithiasis, cholangitis, and cholecystitis.

Clinical Presentation

Abdominal pain is the cardinal symptom of pancreatitis and often is severe, typically in the upper abdomen with radiation to the back. The pain is often relieved by sitting up and leaning forward and is exacerbated by food. Patients commonly experience nausea and vomiting that is precipitated by oral intake. They may have low-grade fever (if temperature is > 101 °F, one should suspect infection) and are often volume depleted because of the vomiting and inability to tolerate oral intake. The inflammatory process may cause third spacing, with sequestration of large volumes of fluid in the peritoneal cavity additionally leading to intravascular depletion. Hemorrhagic pancreatitis with blood tracking along fascial planes would be suspected if periumbilical ecchymosis (Cullen sign) or flank ecchymosis (Grey Turner sign) is present.

During the physical examination, those with acute pancreatitis may appear noticeably uncomfortable. On initial and repeat examinations, it is important to take note of the vitals since fever, hypotension, hypoxia, and tachypnea may alter subsequent management and diagnosis. Common findings on examination include epigastric pain with or without pain in the RUQ; pain can vary greatly in severity. Jaundice, abdominal distention, and presence or absence of bowel sounds are also important to note.

The common test used to diagnose pancreatitis is an elevated serum lipase level. It is more specific than serum amylase to support the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Levels remain elevated in the bloodstream longer than amylase. Serum amylase is not specific to the pancreas, however, and can be elevated as a consequence of many other abdominal processes, such as gastrointestinal ischemia with infarction or perforation; even just the vomiting associated with pancreatitis can cause elevated amylase of salivary origin. It is released from the inflamed pancreas within hours of the attack and remains elevated for 3 to 4 days. When the diagnosis is uncertain or when complications of pancreatitis are suspected, computed tomographic (CT) imaging of the abdomen is highly sensitive for showing the inflammatory changes in patients with moderate-to-severe pancreatitis.

Treatment

Treatment is mainly supportive and includes “pancreatic rest,” that is, withholding food or liquids by mouth until symptoms subside, and adequate narcotic analgesia. Intravenous fluids are necessary for maintenance and to replace any deficits. In patients with severe pancreatitis who sequester large volumes of fluid in their abdomen as pancreatic ascites, considerable amounts of parenteral fluid replacement are necessary to maintain intravascular volume. ERCP with papillotomy to remove bile duct stones may lessen the severity of gallstone pancreatitis and is usually done within 24 to 48 hours. When pain has largely subsided and the patient has bowel sounds, oral clear liquids can be started and the diet advanced as tolerated.

Most patients with acute pancreatitis will recover spontaneously and have a relatively uncomplicated course. Several scoring systems have been developed in an attempt to identify the 15% to 25% of patients who will have a more complicated course, including the Bedside Index for Severity of Acute Pancreatitis (BISAP) score and Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score. Patients with severe acute pancreatitis may require management in a monitored or intensive care unit. The most common cause of early death in patients with pancreatitis is hypovolemic shock, which is multifactorial: third spacing and sequestration of large fluid volumes in the abdomen, as well as increased capillary permeability. Others develop pulmonary edema, which may be noncardiogenic due to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or cardiogenic as a consequence of myocardial dysfunction.

Complications

Pancreatic complications include a phlegmon, which is a solid mass of inflamed pancreas, often with patchy areas of necrosis. Sometimes, extensive areas of pancreatic necrosis develop within a phlegmon. Either necrosis or a phlegmon can become secondarily infected, resulting in pancreatic abscess. Abscesses typically develop 2 to 3 weeks after the onset of illness and should be suspected if there is fever or leukocytosis. If pancreatic abscesses are not drained, mortality approaches 100%. Pancreatic necrosis and abscess are the leading causes of death in patients after the first week of illness. A pancreatic pseudocyst is a collection of inflammatory fluid and pancreatic secretions; unlike true cysts, these do not have an epithelial lining. Most pancreatic pseudocysts resolve spontaneously within 6 weeks, especially if they are smaller than 6 cm. However, if they are causing pain, are large or expanding, or become infected, they usually require drainage. Any of these local complications of pancreatitis should be suspected if persistent pain, fever, abdominal mass, or persistent hyperamylasemia occurs.

CLINICAL APPROACH TO CHOLELTHIASIS

Pathophysiology

Gallstones usually form as a consequence of precipitation of cholesterol microcrystals in bile. They are very common, occurring in 10% to 20% of patients older than 65 years. Patients are often asymptomatic. When discovered incidentally, they can be followed without intervention, as only 10% of patients will develop any symptoms related to their stones within 10 years. When patients do develop symptoms because of a stone in the cystic duct or Hartmann pouch, the typical attack of biliary colic is sudden in onset, often precipitated by a large or fatty meal, with severe steady pain in the RUQ or epigastrium, lasting between 1 and 4 hours. They may have mild elevations of the alkaline phosphatase level and slight hyperbilirubinemia, but elevations of the bilirubin level over 3 g/dL suggest a common duct stone. The first diagnostic test in a patient with suspected gallstones usually is an ultrasonogram. The test is noninvasive and very sensitive for detecting stones in the gallbladder as well as intrahepatic or extrahepatic biliary duct dilation.

Treatment

Patients with asymptomatic gallstones do not require treatment; they can be observed and treated if symptoms develop. Cholecystectomy is performed for patients with symptoms of biliary colic or for those with complications.

One of the most common complications of gallstones is acute cholecystitis, which occurs when a stone becomes impacted in the cystic duct, and edema and inflammation develop behind the obstruction. This is apparent ultrasonographically as gallbladder wall thickening and pericholecystic fluid; it is characterized clinically as a persistent RUQ abdominal pain, with fever and leukocytosis. Cultures of bile in the gallbladder often yield enteric flora such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella. If the diagnosis is in question, nuclear scintigraphy with a hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan may be performed. The positive test shows visualization of the liver by the isotope, but nonvisualization of the gallbladder may indicate an obstructed cystic duct. Treatment of acute cholecystitis usually involves making the patient nil per os (NPO; nothing by mouth), intravenous fluids and antibiotics, and early cholecystectomy within 48 to 72 hours.

Another complication of gallstones is cholangitis, which occurs when there is intermittent obstruction of the common bile duct, allowing reflux of bacteria up the biliary tree, followed by development of purulent infection behind the obstruction. If the patient is septic, the condition requires urgent decompression of the biliary tree, either surgically or by ERCP, to remove the stones endoscopically after performing a papillotomy, which allows the other stones to pass.

CASE CORRELATION

- See also Case 20 (Peptic Ulcer Disease), Case 21 (Colitis and Inflamma-tory Bowel Disease), and Case 22 (Acute Diverticulitis).

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

25.1 A 43-year-old man is admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. His family shares that he is a heavy user of alcohol. He is given intravenous hydration and is placed NPO. Which of the following findings is the highest predictor of mortality?

A. His age

B. Initial serum glucose level of 60 mg/dL

C. BUN of 18 mg/dL

D. Disorientation, with Glasgow Coma Scale score of 10

E. Amylase level of 1000 IU/L

25.2 A 37-year-old woman was being followed by her primary provider for symptomatic gallstones, which were confirmed on ultrasonography. She was placed on a low-fat diet and was doing well for the past 3 months. However, today, she presents to the emergency center with severe RUQ pain and nausea. On examination, her temperature is 102.3 °F, heart rate 100 bpm, and blood pressure 120/70 mm Hg. Her abdominal examination reveals marked RUQ tenderness and guarding. There is no rebound tenderness. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Acute cholangitis

B. Acute cholecystitis

C. Acute pancreatitis

D. Acute perforation of the gallbladder

25.3 A 45-year-old man was admitted for acute pancreatitis, thought to be a result of blunt abdominal trauma. After 3 months, he still has epigastric pain but is able to eat solid food. His amylase level is elevated at 260 IU/L. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Recurrent pancreatitis

B. Diverticulitis

C. Peptic ulcer disease

D. Pancreatic pseudocyst

ANSWERS

25.1 D. Impaired mental status is a poor prognostic sign. Other findings associated with higher mortality include a BUN > 25 mg/dL (not 18 mg/dL, as in answer C), presence of SIRS, age over 60 (not 43 years of age, as in answer A), and presence of a pleural effusion. Notably, the amylase level (answer E) does not correlate with the severity of the disease. Thus, although the serum amylase level or lipase level helps to make a diagnosis of pancreatitis, it is the presence of other findings that dictates prognosis. Hyperglycemia with a serum glucose exceeding 200 mg/dL indicates significant pancreatic dysfunction and is a poor prognostic factor; this patient’s glucose level of 60 mg/dL (answer B) is therefore not a significant prognostic indicator.

25.2 B. Acute cholecystitis is one of the most common complications of gallstones. This patient with fever, RUQ pain, and a history of gallstones likely has acute cholecystitis. Acute cholangitis (answer A) usually presents with Charcot triad (RUQ pain, jaundice, and fever/chills) due to an ascending infection proximal to an obstructed bile duct. There is no description of icterus. Acute pancreatitis (answer C) is a complication of gallstones, but affected patients typically present with midline epigastric pain radiating to the back. Acute perforation of the gallbladder (answer D) is a rare complication of cholecystitis that is life threatening; associated findings include high fever, nausea, vomiting, and severe abdominal tenderness with rebound. Treatment is generally surgical, and early diagnosis is important to reduce mortality.

25.3 D. A pancreatic pseudocyst has a clinical presentation of abdominal pain and mass and persistent hyperamylasemia in a patient with prior pancreatitis. The fact that the patient’s pain has largely abated and he is able to eat food speaks against recurrent pancreatitis (answer A). Acute diverticulitis (answer B) usually presents with the acute onset of left lower quadrant abdominal tenderness, fever, and nausea. Peptic ulcer disease (answer C) presents with burning epigastric pain that radiates to the back.

CLINICAL PEARLS

▶ The three most common causes of acute pancreatitis in the United States are gallstones, alcohol consumption, and hypertriglyceridemia.

▶ Acute pancreatitis usually is managed with pancreatic rest, intravenous hydration, and analgesia, often narcotics.

▶ Pancreatic complications (phlegmon, necrosis, abscess, pseudocyst) should be suspected if persistent pain, fever, abdominal mass, or persis-tent hyperamylasemia occurs.

▶ Patients with asymptomatic gallstones do not require treatment; they can be observed and treated if symptoms develop. Cholecystectomy is performed for patients with symptoms of biliary colic or for those with complications.

▶ Acute cholecystitis is best treated with antibiotics and then cholecystec-tomy, generally within 48 to 72 hours.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.