Acute Glomerulonephritis Case File

Eugene C. Toy, MD, Gabriel M. Aisenberg, MD

Case 28

A 27-year-old man presents to the outpatient clinic complaining of facial and hand swelling for 2 days. Additionally, he noticed that his urine appears reddish-brown and that he has had less urine output over the last several days. He has no significant medical history. His only medication is ibuprofen, which he took 2 weeks ago for fever and a sore throat that have since resolved. On examination, he is afebrile, with a heart rate of 85 beats per minute (bpm) and blood pressure of 164/98 mm Hg. He has periorbital edema; his fundoscopic examination is normal without arteriovenous nicking or papilledema. His chest is clear to auscultation, his heart rhythm is regular with a nondisplaced point of maximal impulse, and he has no abdominal masses or bruits. He has edema of his feet, hands, and face. A dipstick urinalysis in the clinic shows specific gravity of 1.025 with 3+ blood and 2+ protein, but it is otherwise negative.

▶ What is the most likely diagnosis?

▶ What is the next diagnostic step?

ANSWERS TO CASE 28:

Acute Glomerulonephritis

Summary: A 27-year-old man presents with

- Chief complaint of several days of facial and hand swelling

- Reddish-brown urine of decreased volume

- Dipstick urinalysis that shows hematuria and proteinuria

- History of fever and sore throat 2 weeks ago for which he took ibuprofen

- Hypertensive but afebrile state

- Normal fundoscopic, cardiac, pulmonary, and abdominal examinations

- Edema of the feet, hands, and face, including periorbital edema

Most likely diagnosis: Acute glomerulonephritis (GN).

Next diagnostic step: Examine a freshly spun urine specimen to look for red blood cell (RBC) casts or dysmorphic RBCs, as these are signs of inflammation if present.

ANALYSIS

Objectives

- Be able to differentiate glomerular from nonglomerular hematuria. (EPA 2, 3)

- Understand the clinical features of GN. (EPA 1, 3)

- Evaluate and treat a patient with GN. (EPA 1, 4)

- Be familiar with the evaluation of a patient with nonglomerular hematuria. (EPA 1, 7)

Considerations

A young man without a significant medical history now presents with new onset of hypertension, edema, and hematuria following an upper respiratory tract infection. He has no history of renal disease, does not have manifestations of chronic hypertension, and has not received any nephrotoxins. He does not have other symptoms of inflammatory diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The presentation of acute renal failure, hypertension, edema, and hematuria in a young man with no significant medical history is highly suggestive of glomerular injury. He likely has acute GN, either postinfectious (streptococcal) or immunoglobulin (Ig) A nephropathy. The reddish-brown appearance of the urine could represent hematuria, which was later suggested by dipstick urinalysis (3+ blood); hence, microscopic examination of the urine for RBCs is very important. Together, the history and examination suggest that the patient likely has acute GN, either primary GN of unknown etiology (no concomitant systemic disease is mentioned) or secondary GN as a result of recent upper respiratory infection (postinfectious GN). The next logical step in diagnosing GN should be to examine the precipitate of a freshly spun urine sample for active sediment (cellular components, red cell casts, dysmorphic red cells). If present, these are signs of inflammation and establish the diagnosis of acute GN. Although likely to be present, these markers do not distinguish among the distinct immune-mediated causes of GN; they merely allow us to make the diagnosis of acute GN (primary or secondary). Further evaluation with serologic markers, such as complement levels and antistreptolysin-O (ASO) titers (Table 28–1), may help to further classify the GN.

APPROACH TO:

Glomerulonephritis

DEFINITIONS

GROSS HEMATURIA: Blood in the urine visible to the eye.

HEMATURIA: Presence of blood in the urine.

MICROSCOPIC HEMATURIA: RBCs in the urine that require microscopy for diagnosis.

CLINICAL APPROACH

Pathophysiology

Hematuria. Direct visualization of a urine sample (gross hematuria) or dipstick examination (positive blood) can be helpful; however, the diagnosis of hematuria is made by microscopic confirmation of the presence of red blood cells (microscopic hematuria). The first step in evaluating a patient who complains of

red-dark urine is to differentiate between true hematuria (presence of RBCs in urine) and pigmented urine (red-dark urine). The breakdown products of muscle cells and RBCs (myoglobin and hemoglobin, respectively) are heme-containing compounds capable of turning the color of urine dark red or brown in the absence of true hematuria (RBCs). A dipstick urinalysis positive for blood without the presence of RBCs (negative microscopic cellular sediment) is suggestive of hemoglobinuria or myoglobinuria.

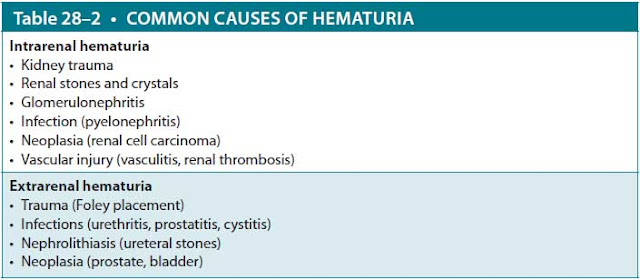

After confirmation, the etiology of the hematuria should be determined. Hematuria can be classified into two broad categories: intrarenal and extrarenal (Table 28–2). The history and physical examination are very helpful in the evaluation (age, fever, pain, family history). Laboratory analysis and imaging studies often are necessary, and considering the potential clinical implications, the etiology of hematuria should be pursued in all cases. First, examination of the cellular urine sediment can help to differentiate glomerular from nonglomerular hematuria. The presence of dysmorphic/fragmented RBCs or red cell casts is indicative of glomerular origin (GN). Second, the urine Gram stain and culture can aid in the diagnosis of infectious hematuria. Third, the urine sample should be sent for cytologic evaluation when the diagnosis of malignancy is suspected. Finally, renal imaging via ultrasound or CT scan can help in the visualization of the renal parenchyma and vascular structures. Cystoscopy can be used to assess the bladder.

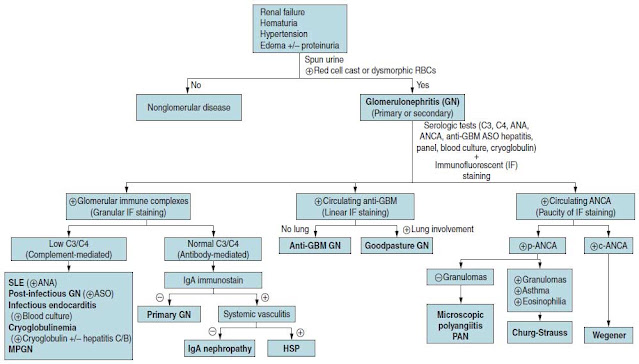

Differential Diagnosis for Glomerular Disease. The approach to the patient with glomerular disease should be systematic and undertaken in a stepwise fashion. The history should be approached meticulously, looking for evidence of preexisting renal disease, exposure to nephrotoxins, and especially any underlying systemic illness. Serologic markers of systemic diseases should be obtained, if indicated (Figure 28–1) in order to further classify the GN. Once the appropriate serologic tests have been reviewed, a kidney biopsy may be required. A biopsy sample can be examined under the light microscope in order to determine the primary histopathologic injury to the nephron (membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis [MPGN], crescentic GN, etc). Further examination of an immunofluorescent-stained sample for immune recognition (IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, C4, or pauci-immune staining) of the affected glomerular membrane (capillary, epithelial, etc) and inspection under electron microscopy for characteristic patterns of immune deposition (granular, linear GN) may provide a definitive diagnosis of the immune-mediated injury to the glomeruli. Figure 28–1 shows an algorithmic approach to the patient with acute GN.

Figure 28–1. Algorithm of approach to the patient with acute glomerulonephritis. Abbreviations: ANA, antinuclear antibody; ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; ASO, antistreptolysin-O; c-ANCA, cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; GBM, glomerular basement membrane; HSP, Henoch-Schönlein purpura; MPGN, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis; MPO-ANCA, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; p-ANCA, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; PAN, periarteritis nodosa; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

A common clinical scenario is the need to distinguish between postinfectious (usually streptococcal) GN and IgA nephropathy. Both illnesses can present with GN occurring after an upper respiratory illness. The history can sometimes provide a clue. In poststreptococcal GN (PSGN), the GN typically does not set in until several weeks after the initial infection. In contrast, IgA nephropathy may present with pharyngitis and GN at the same time. In addition, PSGN classically presents with hypocomplementemia (predominantly low C3), and if the patient undergoes a renal biopsy, there is evidence of an immune complex–mediated process. In contrast, IgA nephropathy has normal complement levels and negative ASO titer (IgA levels may be elevated in about a third of patients, but this is nonspecific), and the renal biopsy will show mesangial IgA.

Clinical Presentation

Glomerular disease is encountered mainly in the form of two distinct syndromes: nephritic or nephrotic (or sometimes an overlap of the two syndromes). Nephritis (nephritic syndrome) is defined as an inflammatory renal syndrome that presents as hematuria, edema, hypertension, and a low degree of proteinuria (< 1-2 g/d). Nephrosis (or nephrotic syndrome) is a noninflammatory (no active sediment in the urine) glomerulopathy that causes heavy proteinuria. Nephrotic syndrome is distinguished by four features: (1) edema, (2) hypoalbuminemia, (3) hyperlipidemia, and (4) proteinuria (> 3 g/d). Glomerular injury may result from a variety of insults and presents either as the sole clinical finding in a patient (primary renal disease) or as part of a complex syndrome of a systemic disorder (secondary glomerular disease). For the purpose of this discussion, GN includes only the inflammatory glomerulopathies.

Nephritic Syndrome. The presentation of acute renal failure with associated hypertension, hematuria, and edema is consistent with acute GN. Acute kidney injury, as manifested by a decrease in urine output and azotemia, results from impaired urine production and ineffective filtration of nitrogenous waste by the glomerulus. Common signs suggesting an inflammatory glomerular cause of renal failure (ie, acute GN) include hematuria (caused by ruptured capillaries in the glomerulus), proteinuria (caused by altered permeability of the capillary walls), edema (caused by salt and water retention), and hypertension (caused by fluid retention and disturbed renal homeostasis of blood pressure). The presence of this constellation of signs in a patient makes the diagnosis of GN very likely. However, it is important to note that often patients present with an overlap syndrome, sharing signs of both nephritis and nephrosis. Moreover, the presence of hematuria in itself is not pathognomonic for GN because there are multiple causes of hematuria of nonglomerular origin. Therefore, confirmation of the presumptive diagnosis of acute GN requires microscopic examination of a urine sample from the patient.

The presence of red cell casts (inflammatory casts) or dysmorphic RBCs (caused by filtration through damaged glomeruli) in a sample of spun urine establishes the diagnosis of GN.

Once the diagnosis of acute GN is made, it can be broadly classified as either primary (present clinically as a renal disorder) or secondary (renal injury caused by a systemic disease). The specific diagnosis can usually be established by clinical history and serologic evaluation and often requires a kidney biopsy (Table 28–3).

Treatment

Treatment depends on the diagnosis of the GN, whether it is a primary renal disease or secondary to a systemic illness. When appropriate, the underlying disease should be treated (infective endocarditis, hepatitis, SLE, or vasculitis). The use of steroids and cyclophosphamide has been advocated in the treatment of GN induced by antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, while other antibody-mediated GNs might require plasmapheresis in order to eliminate the inciting antibody-immune complex. Treatment for PSGN is usually supportive, with control of hypertension and edema, with a very good prognosis. There is no clearly defined treatment for IgA nephropathy. However, general interventions to slow progression include blood pressure control with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers, as well as corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents to reduce underlying inflammatory disease.

CASE CORRELATION

- See also Case 29 (Nephrotic Syndrome and Diabetic Nephropathy) and Case 30 (Acute Kidney Injury).

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

28.1 An 18-year-old marathon runner has been training during the summer. He is brought to the emergency department disoriented after collapsing on the track. His temperature is 102 °F. A Foley catheter is placed and reveals reddish urine with 3+ blood on dipstick and no cells seen microscopically. Which of the following is the most likely explanation for his urine?

A. Underlying renal disease

B. Prerenal azotemia

C. Myoglobinuria

D. Glomerulonephritis

28.2 An 8-year-old boy is brought into the pediatrician’s office for fatigue, pain of the joints, and red-brown colored urine of 2 days. On examination, the blood pressure is 140/92 mm Hg, and heart rate is 90 beats per minute. He has facial swelling and pedal edema. The heart, lung, and abdominal examinations are normal. His mother states that about 3 weeks ago he had a sore throat and fever. Which of the following laboratory findings would most likely be present?

A. Elevated serum complement levels

B. Positive antinuclear antibody titers

C. Elevated ASO titers

D. Positive blood cultures

E. Positive cryoglobulin titers

28.3 A 22-year-old man complains of acute hemoptysis over the past week. He denies smoking, fever, or preexisting lung disease. His blood pressure is 130/70 mm Hg, and his physical examination, including lung examination, is normal. His urinalysis shows microscopic hematuria and RBC casts. Which of the following is the most likely etiology?

A. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the lungs

B. Acute tuberculosis of the kidneys and lungs

C. Systemic lupus erythematosus

D. Goodpasture disease (antiglomerular basement membrane)

ANSWERS

28.1 C. This individual is suffering from heat exhaustion, which can lead to rhabdomyolysis and release of myoglobin. Myoglobinuria leads to a reddish appearance and positive urine dipstick reaction for blood, but microscopic analysis of the urine likely will demonstrate no red cells. Based on the history, this diagnosis is most likely, and the other answer choices (answer A, underlying renal disease; answer B, prerenal azotemia; and answer D, glomerulonephritis) are not as likely.

28.2 C. This child most likely has postinfectious GN based on the fever and pharyngitis 3 weeks previously and now with hypertension, facial and pedal edema, and hematuria. The ASO titers typically are elevated, and serum complement levels are decreased (not increased, as in answer A) in PSGN. Answer B (positive antinuclear antibody titers) would be more likely seen in a patient with lupus nephritis along with decreased complement levels (C3 and C4). Answer D (positive blood cultures) is more likely in a patient with GN secondary to endocarditis, where valvular disease would also be present. Answer E (positive cryoglobulin titers) is indicative of GN secondary to cryoglobulinemia, where the patient is also likely to test positive for hepatitis C.

28.3 D. Goodpasture (antiglomerular basement membrane) disease typically affects young males, who present with hemoptysis and hematuria. Antibody against type IV collagen, expressed in the pulmonary alveolar and glomerular basement membrane, leads to the pulmonary and renal manifestations. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis typically affects older adults and includes more systemic symptoms such as arthralgias, myalgias, and sinonasal symptoms; these patients are positive for ANCA. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the lungs (answer A) is not as likely due to the patient’s young age and since he is not a smoker. Acute tuberculosis of the lungs and kidneys (answer B) is not usual, and since the patient does not have a travel history, night sweats, weight loss, or fever, this is not likely. Systemic lupus erythematosus (answer C) can cause GN (hematuria) but not hemoptysis; pleuritis is the typical pulmonary manifestation.

CLINICAL PEARLS

▶ Finding RBC casts or dysmorphic RBCs on urinalysis differentiates glomer-ular bleeding (eg, GN) from nonglomerular bleeding (eg, kidney stones).

▶ Glomerulonephritis is characterized by hematuria, edema, and hypertension caused by volume retention.

▶ Gross hematuria following an upper respiratory illness suggests either IgA nephropathy or PSGN.

▶ Patients with nonglomerular hematuria and no evidence of infection should undergo investigation with imaging (noncontrast helical com-puted tomography, ultrasound, or intravenous pyelogram) or cystoscopy to evaluate for stones or malignancy.

REFERENCES

Hricik DE, Chung-Park M, Sedor JR, et al. Glomerulonephritis. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:888-899.

Johnson RJ, Freehally J, Floege J, Tonelli M, eds. Comprehensive Clinical Nephrology. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2018.

Lewis JB, Neilson EG. Glomerular diseases. In: Jameson J, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Loscalzo J, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 20th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2018.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.