Cerebral Concussion Case File

Eugene C. Toy, MD, Ericka Simpson, MD, Pedro Mancias, MD, Erin E. Furr-Stimming, MD

CASE 10

A 15-year-old right-handed adolescent boy presents to the clinic 1 day after suffering a head injury during football practice. He complains of headache, nausea, and light sensitivity. He denies any neck pain or any other new focal neurologic complaints. Immediately following his injury, the athletic trainer noted that he was oriented only to the place and the name of his coach. He had no memory of the series of plays immediately prior to being tackled. His speech was quite slow and deliberate. His pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light, and he had no facial asymmetry. Finger-to-nose testing was somewhat slow and deliberate with mild past-pointing. His gait was mildly wide-based and unsteady. When tested again 15 minutes after his injury, he was oriented to person, place, and time, but he still had no memory of the events preceding his injury, and his gait remained unsteady. He was taken to a local emergency center for further evaluation. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain revealed no acute abnormalities, and he was discharged with follow up instructions. Your examination reveals some mild instability when he stands with his feet together and closes his eyes, but otherwise the neurologic examination is unremarkable. He has no significant neurologic or medical history and was not taking any medications. He was not suffering from any kind of illness recently. There was no history of neurologic problems in the family.

▶ What is the most likely diagnosis?

▶ What is the next diagnostic step?

▶ What is the next step in therapy?

ANSWERS TO CASE 10:

Cerebral Concussion

Summary: This is a case of a previously healthy and neurodevelopmentally normal 15-year-old adolescent boy who experienced a head injury during a football game with new-onset mild but persistent nonfocal neurologic symptoms. He is now in the clinic seeking further evaluation and treatment.

- Most likely diagnosis: Concussion.

- Next diagnostic step: Serial examinations, including standardized concussion testing.

- Next step in therapy: Rest, symptomatic treatment, reassurance, and education on a progressive return-to-activity plan.

- Be aware of the epidemiology of concussion.

- Be able to recognize the signs and symptoms of concussion.

- Understand the clinical criteria for obtaining imaging following a head injury.

- Be aware of initial concussion management, including “return-to-play” guidelines for sports-related concussions.

- Describe clinical features and the usual course of the postconcussion syndrome.

Considerations

The neurologic status of this 15-year-old adolescent boy is now steadily improving following his sports-related concussion. Always err on the side of caution when evaluating head traumas, particularly in the pediatric and adolescent setting. Transfer to the emergency department was a reasonable response. While a CT scan cannot diagnose concussion, it will rule out more severe injury such as an intracranial hemorrhage. The most important part of his care at this time will be education on the management and expected outcome of the concussion.

APPROACH TO:

Cerebral Concussion

DEFINITIONS

CONCUSSION: A traumatic alteration in cerebral physiologic function with or without loss of consciousness. Concussion is best thought of as a mild traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Data derived from AAN Summary of evidenced-based guideline update: evaluation and management of concussion in sports, 2013.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

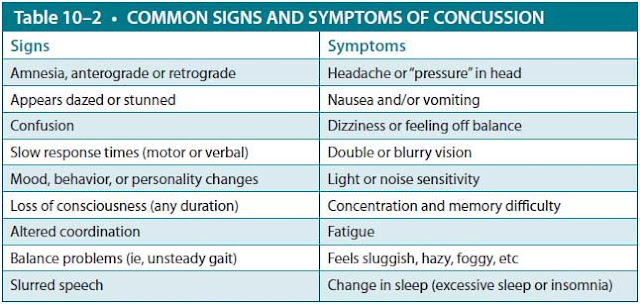

Between 1.6 and 3.8 million sports-related mild TBIs occur each year in the United States. The rate continues to rise, but this is still likely an underestimate due to underdiagnosis. For males, the sport with highest risk of concussion is football (Table 10–1). In women’s sports, the rate of concussion is highest in soccer and basketball. In fact, even though males sustain more concussions, female athletes have a higher rate of concussions than males when compared within the same sport. Rugby, ice hockey, wrestling, and lacrosse also account for higher rates of concussions. Between 2009 and 2013, all 50 states in the United States passed legislature regarding concussions in sports for youth and students.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The clinical syndrome following exposure to a rapid acceleration/deceleration force results in diffuse metabolic derangement in the brain involving impaired neurotransmitter function, excitotoxicity, and disrupted ion homeostasis. Diffuse axonal injury due to stretching and shearing may also play a role. Since the ascending reticular-activating system (ARAS) is a key structure mediating wakefulness, transient interruption of its function can be partly responsible for temporary loss of consciousness following a head injury. The junction between the thalamus and the midbrain, which contains reticular neurons of the ARAS, seems to be particularly susceptible to the forces produced by rapid deceleration of the head as it strikes a fixed object.

CONCUSSION DIAGNOSIS

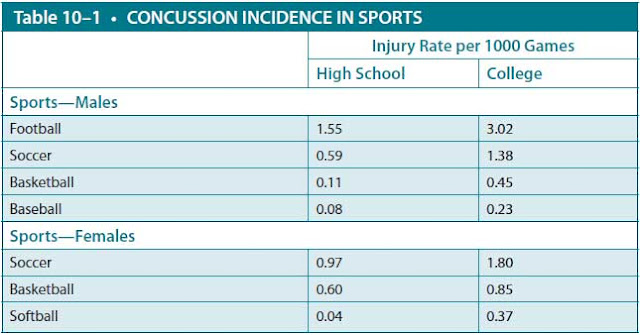

The diagnosis is based on history, clinical examination, and physician experience. Even the most skilled examiner may have difficulty with making a definitive diagnosis in some cases due to the lack of an objective test. Imaging will not aid in the diagnosis of concussion, but it will allow one to rule out more severe and/or concomitant intracranial pathology. The previous American Academy of Neurology grading system of concussion severity is no longer used; current recommendations place the emphasis on unique patient cases in diagnosing and managing the injury. Headache is the most common acute symptom, occurring in 90% of patients (Table 10–2). Based on the examiner’s degree of certainty, the concussion may be designated as possible, probable, or definite.

INITIAL MANAGEMENT OF CONCUSSION

If a concussion is suspected, the person should be removed from physical activity until they can undergo further evaluation by a medical professional. Assessment of airway, breathing, and circulation is followed by a neurologic examination. Several tools have been developed to help with assessment, such as the Post-Concussion Symptom Scale, Graded Symptom Checklist, Standardized Assessment of Concussion, Balance Error Scoring System, Sensory Organization Test, Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 3 (SCAT3), and Immediate Post-Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing (ImPACT). Most of these tools are readily available online for free and can be administered reliably even by nonphysicians. Assessment with one of the aforementioned diagnostic tools acutely following the injury (ie, in the locker room 5 minutes after the injury) may be useful in tracking the recovery over time. Of note, symptoms may continue to develop over several hours following the injury, and the patient should be monitored closely for the next 24 to 48 hours. No athlete with a suspected concussion can return to play on the same day as the injury.

Urgent evaluation in the emergency room should be pursued if the patient has evidence of new or worsening neurologic signs, focal deficits, potential spinal injury, and/or a Glasgow Coma Scale score of less than 15. Red flags for a cervical injury include new-onset numbness or weakness, neck pain, and respiratory difficulty. If a cervical spine injury is suspected, the spine should be immobilized and any headgear should remain in place until removed by a trained health care provider. Intracranial hemorrhage should be considered after any head trauma, though the incidence is relatively low. A noncontrast CT scan is the imaging study of choice to assess for bleeding. Indications include loss of consciousness, altered or worsening mental status, severe or worsening headache, anisocoria, seizure, focal deficits, and repeated vomiting. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is not necessary and would only be considered later if the concussive syndrome does not resolve as expected. Always consider the individual patient and situation in your clinical decision-making.

Once the diagnosis is made, care focuses on symptom management. While in the acute symptomatic phase, patients should limit physical and mental activity. This includes sports play, some school work, and “screen time” on the computer, tablet, or phone. Acetaminophen may be given in the first 48 hours for pain. If there is no hemorrhage, anti-inflammatory medications such as ibuprofen may be added later if needed. Frequent follow-up with a physician is important to ensure symptoms are improving and adequately treated. A neuropsychologist may be consulted to help in the evaluation, monitoring, and eventual return-to-play decisions. As symptoms begin to improve, the patient may try a slow return-to-school/work and social activities. Modifications in length of time spent in school or on assignments may be needed until symptoms improve. When the patient has no signs or symptoms of concussion at rest, then they may begin a gradual return to physical activity.

RETURN-TO-PLAY GUIDELINES

For sports-related concussions, an important consideration is when the athlete will be able to return to playing. Determining when an athlete returns to play after a concussion should follow an individualized course since each athlete will recover at a different pace. Under no circumstances should any athlete return to play the same day the concussion occurred. No athlete should return to play while still symptomatic at rest or with exertion. Although the vast majority of athletes with concussions will become asymptomatic within a week of their concussions, numerous studies have demonstrated a longer recovery of full cognitive function in younger athletes compared with college-aged or professional athletes—often 7 to 10 days or longer. Because of this longer cognitive recovery period, although they are asymptomatic, there should be a more conservative approach to deciding when pediatric and adolescent athletes can return to play. A matter of ongoing debate is the issue of when an athlete should retire (whether in high school or playing at a professional level) from a sport in which they have sustained multiple concussions. These recommendations apply to athletes experiencing their first concussion of the season. For a second concussion, even more conservative management should be employed. Studies show that recurrent concussions are associated with prolonged recovery time and more severe symptoms with loss of consciousness than those with first time concussion injury. A postconcussion-rehabilitative approach should be employed for all concussion cases. The program should be characterized by a stepwise incorporation of activity between 1- and 5-day increments based on the individual’s injury and rate of recovery (Table 10–3). If symptoms reoccur, the athlete should return to rest for 24 hours and then resume activity at the last stage that was well tolerated.

COMPLICATIONS

SECOND-IMPACT SYNDROME: This is a rare but life-threatening syndrome of cerebral vascular congestion and diffuse cerebral edema that may occur when an athlete sustains a second head injury before recovering from the initial injury. Since a history of previous impact is always documented, it remains unclear if the excessive inflammatory response occurs due to the repetitive injury or the mild TBI itself. Pediatric and adolescent patients are at the highest risk for this condition, as most cases have occurred in patients of 20 years or younger.

POSTCONCUSSION SYNDROME: Postconcussion syndrome is the constellation of symptoms, such as headache, dizziness, inability to concentrate, insomnia, and irritability, experienced by the patient following a concussion. While in most patients these symptoms will quickly begin to resolve, some will have persistent symptoms for weeks, months, or years. It is considered chronic if symptoms persist longer than 1 year. Patients with a history of a previous concussion are at higher risk for prolonged symptoms with repeat head injury. Inadequate concussion management in the acute and subacute stages can also prolong postconcussion syndrome. Neuropsychology consultation may also be utilized for evaluation of persistent symptoms. It is helpful to educate patients at the time of their initial injury regarding common symptoms and the benign self-limited nature of postconcussion syndrome.

LONG-TERM EFFECTS: There is some evidence to suggest that chronic neurocognitive impairment can occur in athletes exposed to multiple head injuries. More recently, media and research focus has been on chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a syndrome of progressive cognitive decline and behavior change seen years later in athletes who have sustained multiple head injuries. Some patients may also experience motor symptoms such as tremor, ataxia, and increased tone. Autopsy findings show diffuse brain atrophy and tau deposition.

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

10.1 Which of the following patients should have a CT of the head performed?

A. A 27-year-old man who was momentarily dazed after striking his head on a tree branch but is back to baseline within 5 minutes

B. An 18-year-old ice hockey player who did not lose consciousness after being hit by a flying puck but did have significant dizziness and ataxia that resolved after 30 minutes

C. A 68-year-old man who slipped and hit his head on the pavement, was unconscious for less than 30 seconds, and was back to baseline within

5 minutes

D. A 22-year-old patient who suffered a concussion 1 week ago and who continues to have a mild-to-moderate headache

10.2 Which of the following is true regarding return-to-play guidelines for sports-related concussions?

A. The number of concussions experienced during a season does not matter as long as there is no loss of consciousness.

B. A postconcussion-rehabilitation program should be initiated and

tailored for each individual case.

C. As long as an athlete is symptom-free at rest, they can return to play after the concussion.

D. Any loss of consciousness necessitates removing the athlete from play for the remainder of the season.

10.3 A 15-year-old high school athlete suffered a loss of consciousness during football practice. The parents ask about postconcussion syndrome. Which of the following is the most accurate statement regarding this condition?

A. It is an uncommon sequelae of traumatic brain injury.

B. A characteristic symptom would be progressively increasing lethargy.

C. Many high school athletes feign postconcussion symptoms to avoid schoolwork.

D. It is usually self-limited and resolves over weeks to months.

ANSWERS

10.1 C. Any patient who has experienced loss of consciousness should have a head CT obtained. Also, patients older than 60 years should be imaged given the higher incidence of hemorrhage with increasing age.

10.2 B. A postconcussion-rehabilitation program should be employed for all players, especially young and adolescent players, to ensure appropriate time for recovery and monitoring.

10.3 D. Postconcussion syndrome is a common sequelae of head injury and usually resolves over weeks to months. It is not a form of malingering. Progressively increasing lethargy would be concerning for an evolving hemorrhage or other serious process, and the patient would need further evaluation.

CLINICAL PEARLS

|

▶ A concussion is a traumatic injury to

the brain as a result of a violent blow, shaking, deceleration, or spinning

resulting in altered cerebral function.

▶ No athlete may return to play the

same day they sustain a concussion due to the risk of prolonging their

recovery and the rare occurrence of second-hit syndrome.

▶ All 50 states have laws regarding

concussions in young athletes and return to play. The return-to-play

procedure is a multistep progression from no activity to full participation.

▶ Postconcussion syndrome is the

constellation of cognitive, physical, affective, and sleep symptoms

experienced by a patient after a concussion that may persist for weeks to

months in a small number of patients.

▶ Second-hit syndrome is a rare

inflammatory reaction of malignant

cerebral edema triggered by head

injury in young athletes. It can have devastating outcomes, including death.

|

REFERENCES

Giza CC. Pediatric issues in sports concussions. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2014;20(6):1570-1587.

Giza CC, Kutcher JS. An introduction to sports concussions. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2014;

20(6):1545-1551.

Giza CC, Kutcher JS, Ashwal S, et al. Summary of evidence-based guideline update: evaluation and management of concussion in sports: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;80(24):2250-2257.

Halstead ME, Walter KD. American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical report—sport-related concussion in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):597-615.

Jordan BD. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy and other long-term sequelae. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2014;20(6):1588-1604.

Kutcher JS, Giza CC. Sports concussion diagnosis and management. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2014;20(6):1552-1569.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.