Syphilis Case File

Eugene C. Toy, MD, Gabriel M. Aisenberg, MD

Case 45

A 23-year-old man comes to the clinic. In the chart, the chief complaint is listed as, “Wants a general checkup.” You enter the room and greet a generally healthyappearing young man who seems nervous. He finally admits that he has been worried about a lesion on his penis. He denies pain or dysuria. He has never had any sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and has an otherwise unremarkable medical history. He is afebrile, and his examination is notable for a shallow, clean ulcer without exudates or erythema on the shaft of his penis, which is nontender to palpation and has a cartilaginous consistency. There are some small, nontender, inguinal lymph nodes bilaterally.

▶ What is the most likely diagnosis?

▶ What is the likely treatment?

ANSWERS TO CASE 45:

Syphilis

Summary: A 23-year-old healthy man presents with

- A firm nontender penile ulcer

- Nontender inguinal lymph nodes bilaterally

Most likely diagnosis: Chancre of primary syphilis.

Likely treatment: Single intramuscular injection of benzathine penicillin G.

- Understand the pathogenesis and natural history of Treponema pallidum infection. (EPA 1, 12)

- Name the differential diagnosis of genital ulceration and STIs. (EPA 2)

- Explain how to diagnose syphilis. (EPA 3)

- Describe the treatment of syphilis. (EPA 4)

Considerations

This 23-year-old man reluctantly reveals his concern about a nontender ulcer of the penis. Although he has no history of STIs, the most common cause of a painless ulcer of the genital area in a young, immunocompetent person is syphilis. The STIs often present together, so he should be evaluated for other STIs, such as Chlamydia, gonorrhea, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Other causes of genital ulcers should also be considered, including chancroid and herpes virus (both usually painful), and a superficially infected skin lesion. Compliance with therapy and follow-up are crucial because syphilitic infections can become chronic and lead to cardiovascular and neurologic disease. Additionally, he could transmit the disease to others, including women of childbearing age, who, if infected during pregnancy, could pass the infection to their newborns.

LATENT SYPHILIS: Asymptomatic period between secondary and tertiary syphilis. It is classified as early (up to 1-year duration), late (after 1 year), or of unknown duration.

PRIMARY SYPHILIS: Initial lesion of T. pallidum infection, usually in the form of a firm, nontender ulcer (the chancre).

SECONDARY SYPHILIS: Disseminated infection manifesting in a pruritic, maculopapular diffuse rash that classically involves the palms and soles, or the flat moist lesion of condyloma lata.

TERTIARY (LATE) SYPHILIS: Symptomatic infection involving the central nervous system (CNS), cardiovascular system, or the skin and subcutaneous tissues (gummas).

CLINICAL APPROACH

Epidemiology

Syphilis is classically called one of the “great imitators” for its multifaceted manifestations. After a decline in cases over the prior decades, the incidence of syphilis has been skyrocketing since the 1980s. The public health consequences of late-stage or undiagnosed syphilis can be devastating, so recognizing and correctly treating this disease is of great importance. In 2017, new syphilis cases increased by 10.5% from the previous year, resulting in 30,644 cases of reported primary and secondary disease in the United States. The largest growing demographics include men who have sex with men (MSM) and women (possibly secondary to increased drug use). Other patterns seen were high primary and secondary cases seen in association with HIV coinfection MSM, men living in the western United States, black males, and men aged 20 to 34. Late-stage syphilis also saw increased rates that were associated with the use of screening and confirmatory testing.

Clinical Presentation

Caused by the spirochete T. pallidum, the organism penetrates abraded skin or mucous membranes in order to disseminate through the lymphatics and bloodstream to later involve almost every organ. The most common form of transmission is via sexual exposure through open lesions that are extremely infectious (above 30% transmission rate); on the other hand, cutaneous inoculation has lower risk of transmission. Within 1 week to 3 months of inoculation, a painless papule develops that eventually ulcerates into a chancre, which usually forms at the site of entrance. Multiple ulcers may form in addition with regional lymphadenopathy, but some patients may not notice the ulceration at all. The chancre of syphilis is typically nonerythematous, with rolled borders and a clean base, with a very firm consistency on palpation. It usually is painless, although it may be mildly tender if touched.

The appearance of the chancre represents primary syphilis. Other diseases that present with ulcerations include chancroid caused by Haemophilus ducreyi and herpes simplex infection. Chancroid ulcers are usually painful and exudative, with ragged borders and a necrotic base that bleeds easily. Lymph nodes can also suppurate in chancroid, unlike in syphilis. The ulcers in herpes simplex infections typically are painful, grouped vesicles on an erythematous base that eventually ulcerate.

If untreated, the syphilitic chancre disappears within 2 to 6 weeks, and the disease progresses to a second stage and disseminates widely; characteristically, the patient may present with a pruritic, maculopapular diffuse rash that classically involves the palms and soles. Constitutional symptoms such as fever, myalgias, headache, and weight loss can develop in untreated patients in addition to dermatologic findings such as condyloma lata, a gray papillomatous lesion found in intertriginous areas, and patchy hair loss. Secondary syphilis can also affect the following: the liver, skeletal muscle, kidneys, and CNS.

If still left untreated, the patient will transition into a quiescent, or latent, stage. Although relapses of symptoms of secondary syphilis can occur during this time, they become less frequent over years. Between 25% and 40% of patients will go on to develop late-stage syphilis, which can occur 1 to 30 years after initial infection. The symptoms of this stage result from infiltration and destruction of various tissues as a result of chronic infection. The most frequent clinical presentations involve the CNS (neurosyphilis), cardiovascular system, and diffuse organ involvement. The immune reaction to T. pallidum causes a proliferative, obliterative endarteritis, which involves the vasa vasorum, leading to necrosis of the tunica media and arterial wall. This progressive weakness of the walls leads to the formation of saccular aneurysmal dilations of the aorta. In some organs, such as the skin, liver, and bone, these lesions organize into granulomas with an amorphous or coagulated center called gummas. While benign, gummas create organ dysfunction through their progressive destruction of normal tissue. The phase known as latent syphilis involves the period where the patient fails to show clinical manifestations but has positive serologic testing. This distinction matters when treatment is being considered.

Neurosyphilis is another form of tertiary disease that may occur after secondary disease or from the latent stage. T. pallidum disseminates within the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), before spreading to the vasculature and meninges in the early phase and later the brain and spinal cord in advanced stages. In the CNS, it may cause progressive vasculitis associated with local ischemia, stroke, and gradual focal neurologic deficits. Some patients may exhibit personality changes or even dementia. T. pallidum causes demyelination of the posterior spinal column, leading to a wide-based gait, ataxia, and loss of proprioception (tabes dorsalis); other cranial nerve impairments include the development of the Argyll Robertson, small bilateral pupils that do not constrict when exposed to bright light but do constrict when focused on a nearby object. Lumbar puncture should be performed to exclude neurosyphilis in any patient with previous syphilis diagnosis who develops neurologic or ocular symptoms; evaluation of the CSF should strongly be considered in asymptomatic HIV-infected patients with syphilis with CD4 < 350 cells/mm3 or with a high rapid plasma reagin (RPR) titer (> 1:32) since these conditions greatly increase the risk of CNS infection.

Laboratory Findings. The diagnosis of syphilis is always made indirectly, as the organism has not yet been cultured. Diagnostic tests for T. pallidum are divided into two categories: nontreponemal (nonspecific) and treponemal. Nonspecific serologic tests, such as the RPR and Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) tests, examine the reactivity of serum antibodies against lipid antigens in response to the host reaction to T. pallidum. Despite its sensitivity, the likelihood for false positives is higher at low titers. Therefore, confirmatory testing in the form of specific antibody testing for T. pallidum, such as the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) or microhemagglutination assay for T. pallidum (MHA-TP) test, is the next step. Traditionally, treponemal tests were not utilized until initial screening returned positive; however, technological advances have allowed for them to now serve as initial screening tests for syphilis (known as reverse screening). FTA-ABS and MHA-TP tests determine current serum antibodies against treponemal antigens. Dark-field microscopy, in which scrapings from an ulcer are placed under a phase contrast lens to identify the organisms, remains the classic method of diagnosis but is rarely performed today. Lesion biopsy, such as those performed in secondary syphilis with special stains, also can identify the organisms. A positive CSF VDRL or RPR test in the setting of increased CSF leukocytosis, elevated protein levels, and sometimes with low glucose levels, is suggestive of CNS involvement. False-negative results for the VDRL test in CSF are common; however, clinical suspicion remains crucial for an accurate diagnosis.

Treatment

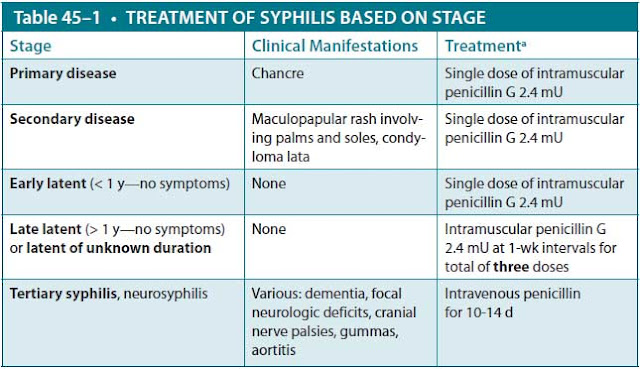

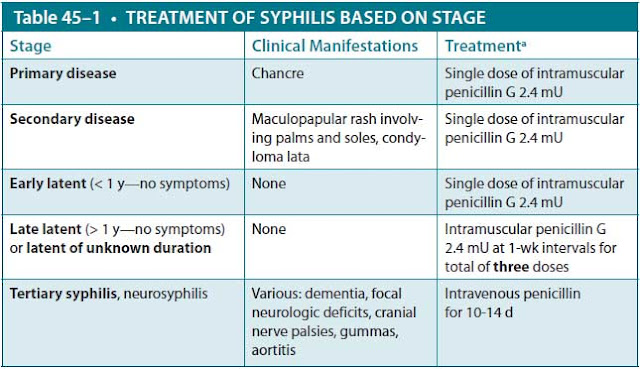

The treatment of choice for syphilis is penicillin, specifically parenteral penicillin G, in all stages. Treatment recommendations vary based on the stage of syphilis (Table 45–1). Individuals with early disease, specifically primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis, may be treated with a single intramuscular injection of benzathine penicillin, a long-lasting intramuscular injection. Alternative therapies include doxycycline or, tetracycline, or for up to 14 days. Ceftriazone IM or IV for 10-14 days has been used but the optimal dosage has not been established. For patients with late latent disease or unknown duration of the latent phase (presumed to be > 1 year), those with cardiovascular manifestations, or those with gummas, treatment consists of three weekly intramuscular injections of benzathine penicillin. Alternative therapies include doxycycline or tetracycline for various time frames.

Neurosyphilis is notoriously difficult to treat. Those with known CNS disease require high doses of intravenous penicillin G for 10 to 14 days; an alternative but inferior therapy is daily IV ceftriaxone for 10 to 14 days. All patients should be followed closely to ensure that their titers fall over the year after treatment. Pregnant women who are allergic to penicillin should be desensitized and then receive penicillin, as this is the only treatment known to prevent congenital infection. The sequelae of congenital syphilis can be devastating; this is why the World Health Organization has developed initiatives to increase prenatal screening and treatment of syphilis.

Prognosis. T. pallidum infection usually leads to a positive specific serologic test (FTA-ABS or MHA-TP) for life, whereas an adequately treated infection will lead to a fall in RPR serology. A normal response is considered a four-fold drop in titers within 3 months and a negative or near-negative titer after 1 year. A suboptimal response may mean inadequate treatment, undiagnosed tertiary disease, or reinfection. In some persons, nontreponemal antibodies can persist, usually in low titers, for a long period of time, a response referred to as the “serofast reaction.” Most patients who have reactive treponemal tests will have reactive tests for the remainder of their lives, regardless of treatment or disease activity.

Nontreponemal titers should be collected prior to treatment initiation, as they can increase shortly after starting therapy. Shortly after starting treatment, a patient can experience constitutional symptoms such as fevers, myalgia, rigors, rash, headache, hypotension, and sometimes even seizures or alterations in mental status. While not completely understood, it is believed that the lysis of infected cells can cause a massive inflammatory response. This phenomenon is referred to as a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction and should not result in stopping treatment.

Prevention. In any patient diagnosed with an STI, the possibility of coinfection with other STIs should be considered. HIV is often asymptomatic early in the course of infection, and screening should be recommended to those persons who have histories of high-risk behaviors or who have evidence of other STIs. Because HIV takes months to undergo seroconversion, the screening strategy should last for that long.

Chlamydia trachomatis is the most common bacterial STI in the United States, and the majority of newly diagnosed patients report being asymptomatic, especially women. In women, it characteristically causes cervicitis (vaginal discharge, postcoital bleeding) and urethritis (dysuria or urinary tract infection symptoms).

If untreated, C. trachomatis can ascend the female reproductive tract, leading to severe abdominal and pelvic pain, adnexal tenderness, worsening cervicitis, vaginal discharge, and dysuria, collectively known as pelvic inflammatory disease. Repeated episodes can result in tubal scarring and increased risk of infertility. Men with symptoms typically present with urethritis (dysuria and urethral discharge), but they may also experience fever, epididymitis, or proctitis with rectal pain or diarrhea. Diagnosis is usually made by antigen detection or gene probe directly from the urethra or cervix. Treatment consists of a single dose of 1000 mg of azithromycin (often given under direct observation) or a 7-day course of doxycycline.

Neisseria gonorrheae, a gram-negative diplococcus, can present with similar clinical syndromes as Chlamydia (in fact, up to 30% of patients are coinfected with both organisms), but patients are more likely to be symptomatic, especially men. Historically, N. gonorrhoeae can initially present as disseminated infection characterized by fever, migratory polyarthritis, tenosynovitis of hands and feet, a rash on the distal extremities, and rare incidences of endocarditis or meningitis. Unlike primary N. gonorrhoeae management, disseminated infection requires hospitalization and intravenous ceftriaxone. Outpatients with genitourinary symptoms are often treated with a single intramuscular injection of ceftriaxone, along with a single dose of azithromycin 1000 mg or doxycycline for a 7-day course for likely Chlamydia coinfection.

CASE CORRELATION

- See also Case 41 (Urinary Tract Infection With Sepsis in the Elderly), Case 42 (Vascular Catheter Infection in a Patient With Neutropenic Fever), Case 43 (Meningitis, Bacterial), and Case 46 (HIV/AIDS and Pneumocystis Pneumonia).

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

45.1 A 25-year-old HIV-negative man presents to your office after being treated for syphilis 1 year ago. He continues to have unprotected sex with multiple partners but denies any symptoms of penile discharge, rash, or fevers. What is the next best step in avoiding transmission of STIs?

A. Empiric treatment of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia

B. Encouraging use of barrier contraception (ie, condoms)

C. Frequent STI screening, including HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia

D. Encouraging abstinence

E. Prescribing this patient PrEP (preexposure prophylaxis)

45.2 As part of normal screening during pregnancy, a 28-year-old patient (gravida 2, para 1) has a positive RPR test with a titer of 1:64 and a positive MHA-TP and is treated with intramuscular penicillin. She returns to your office 3 months later with an RPR titer of 1:8. Which of the following treatments do you offer?

A. Repeat single injection of intramuscular penicillin

B. No treatment is necessary

C. Three injections of intramuscular penicillin weekly

D. Doxycycline

45.3 A 23-year-old man is found to have late latent syphilis (RPR 1:64) as part of a workup following his diagnosis with HIV. He is asymptomatic, has a CD4 count of 150 cells/mm3, and does not remember having lesions or rashes in the past. Prior to starting therapy with penicillin for the syphilis, the patient should undergo which of the following procedures?

A. Lumbar puncture to exclude neurosyphilis

B. Skin biopsy to confirm the diagnosis of syphilis

C. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of his brain and an electroencephalogram (EEG)

D. Skin testing to exclude penicillin allergy

E. Adjustment of his HIV medications to optimize his CD4 count prior to treatment for syphilis

45.4 A 28-year-old woman is seen in the office for “sores” on her vulva area. She denies a recent change in sexual partners and is not aware of any STI. On examination, she is found to have a nontender 1-cm ulcer of the right labia majus. A herpes culture is taken of the ulcer scraping, which is negative. A serum RPR titer is also negative. Which of the following is the next best step?

A. Empiric treatment with doxycycline for C. trachomatis

B. Empiric treatment with acyclovir for herpes simplex virus

C. Empiric treatment with azithromycin for Haemophilus ducreyi

D. Dark-field microscopy/empiric treatment with intramuscular penicillin

E. Biopsy for possible vulvar cancer

ANSWERS

45.1 C. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines, men with high-risk sexual behaviors should be screened at least annually or more frequently for HIV, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis, and treated if they have a positive result. There are no data to support empirically treating for all STIs (answer A). This patient has a history of not using barrier contraception; thus, encouraging abstinence (answer D) and condom use (answer B) are insufficient. There are data to support starting individuals with high-risk sexual practices on PrEP (tenofovir and emtricitabine) to avoid infection with HIV (answer E); however, this will not reduce the patient’s transmission of other STIs at this time.

45.2 B. A four-fold change in titer, equivalent to a change of two dilutions (eg, from 1:16 to 1:4 or from 1:8 to 1:32) is considered necessary to demonstrate a clinically significant difference between two nontreponemal test results obtained using the same serologic test. This patient’s titer has dropped more than four-fold and thus can be considered successfully treated. Therefore, repeat treatment with penicillin is not necessary (answers A and C). Failure of nontreponemal test titers to decline four-fold within 6 to 12 months after therapy for primary or secondary syphilis might be indicative of treatment failure (per the CDC guideline). Doxycycline (answer D) should only be used in a patient who has a true allergy to penicillin and cannot undergo desensitization.

45.3 A. Lumbar puncture to exclude neurosyphilis is generally indicated when any patient with syphilis develops neurologic or ocular symptoms; it is also considered if HIV-infected patients with syphilis have a CD4 count less than 350 cells/mm3 or an RPR titer exceeding 1:32. Skin biopsy (answer B) is not the way to diagnose syphilis; rather, diagnostic procedures include serology or, if very early, scraping with dark-field analysis. MRI and EEG (answer C) are not indicated in an asymptomatic patient and would not diagnose CNS syphilis. Skin testing for penicillin allergy (answer D) is not indicated unless the patient had a history of severe allergic reactions. Adjustment of HIV medications prior to penicillin (answer E) is not indicated, and once the stage of syphilis is ascertained, treatment should be started.

45.4 D. Approximately one-third of patients who have the primary lesion of the chancre will have negative serology. They will require either dark-field microscopy or biopsy with special stains to identify the spirochetes; the organism is too thin to be visualized by conventional light microscopy. Empiric treatment with penicillin is reasonable if dark-field microscopy is not available. Chancroid (answer C) is much less likely due to the epidemiologic considerations, and usually this condition is painful. Genital herpes (answer B) and chancroid should produce painful genital ulcers, and Chlamydia (answer A) should cause nonulcerative cervicitis or urethritis. Biopsy for vulvar cancer (answer E) is indicated for an older patient or a persistent ulcer, but it is not indicated in this patient.

CLINICAL PEARLS

▶ Syphilitic chancres are generally clean, painless, ulcerative lesions that resolve in 2 to 6 weeks if untreated; the eruption of a maculopapular rash on the palms and soles signifies secondary syphilis.

▶ Elevated RPR and VDRL tests are nonspecific and may be falsely positive in several normal conditions (pregnancy) and disease states (systemic lupus erythematosus).

▶ Specific treponemal antibody tests, such as the MHA-TP and the FTA-ABS test, should be performed for confirmation of a syphilis diagnosis, but once positive, they usually stay positive for life.

▶ The reverse testing algorithm has advantages over traditional testing in that T. pallidum antibodies (1) are specific to syphilis, (2) are more sensitive than VDRL testing or RPR titer for detecting both primary and late syphilis, (3) can be tested using automated instruments, and (4) can provide a more rapid time to result. The biggest clinical impact of the reverse algorithm is the recognition of untreated late latent syphilis.

▶ Current screening now is utilizes the specific treponemal antibody tests first (reverse screening) due to their higher specificity for syphilis infection.

▶ A declining RPR titer can be followed to test the efficacy of therapy, and if levels fail to decline or increase, it can point at incomplete treatment, failed therapy, or possible reinfection.

▶ Central nervous system involvement can be excluded only through testing of the CSF.

▶ Treatment of syphilis is based on stage: Early syphilis can be treated with a single intramuscular injection of penicillin; late latent syphilis can be treated with three weekly injections; and neurosyphilis or tertiary syphilis can be treated with intravenous penicillin for 10 to 14 days.

▶ If a patient presents with a positive titer and has reported past treatment, it is important to confirm with the state health department to avoid re-treating.

REFERENCES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep (MMWR). 2015;64(RR3):1-137.

Clark EG, Danbolt N. The Oslo study of the natural course of untreated syphilis: an epidemiologic investigation based on a re-study of the Boeck-Bruusgaard material. Med Clin North Am. 1964;48:613.

Lukehart SA. Syphilis. In: Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 19th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2015:1132-1140.

Kidd SE, Grey JA, Torrone EA, et al. Increased methamphetamine, injection drug, and heroin use among women and heterosexual men with primary and secondary syphilis—United States, 2013–2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep (MMWR). 2019;68(6):144-148.

Marra CM, Maxwell CL, Smith SL, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities in patients with syphilis: association with clinical and laboratory features. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:369-376.

World Health Organization. Elimination of mother-to-child transmission (EMTCT) of HIV and syphilis: global guidance on criteria and processes for validation. 2017. 2nd ed. https://www.who

.int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/9789241505888/en/. Accessed July 15, 2019.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.