Optic Neuritis Case File

Eugene C. Toy, MD, Ericka Simpson, MD, Pedro Mancias, MD, Erin E. Furr-Stimming, MD

CASE 23

A 23-year-old, right-handed Caucasian woman is being evaluated for 1 week of gradually worsening vision in her left eye. The patient also reports pain with left eye movement that started at the same time. The patient denied a history of trauma, redness, discharge, or headache. She denies any significant past medical or surgical history and does not take any medication. The examination revealed a visual acuity of 20/20 in the right eye and 20/40 in the left with diminished color perception. The examination revealed no ptosis. Her pupils were reactive to light, constricting from 4 to 2 mm on the right, but only 4 to 3 mm on the left. When light is swung from the right eye to the left eye, the left eye appears to dilate slightly. Extraocular movements were intact in both eyes, though the patient complained of pain in the left with movement. Slit-lamp examination was normal in both eyes. Dilated examination was normal in both eyes with no disc edema. Formal visual field testing revealed an enlarged blind spot in the left eye. The rest of the neurologic examination was normal.

▶ What is the most likely diagnosis?

▶ What is the next diagnostic step?

▶ What is the next step in therapy?

ANSWERS TO CASE 23:

Optic Neuritis

Summary: A 23-year-old right-handed woman is being evaluated for unilateral, subacute, painful loss of vision that is not associated with any systemic or other neurologic symptoms. She has a left relative afferent pupillary defect, and although extraocular movements are intact in both eyes, the patient reports pain with eye movement.

- Most likely diagnosis: Optic neuritis (ON).

- Next diagnostic step: ON is a clinical diagnosis that is made on the basis of the history and physical examination. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain should be performed, preferably within 2 weeks of the onset of symptoms to evaluate the optic nerve and other brain regions.

- Next step in therapy: Short course of intravenous methylprednisolone.

- Understand the differential diagnosis of monocular visual compromise.

- Describe the clinical manifestation of ON.

- Understand the relationship of ON and multiple sclerosis (MS).

- Understand when and how to treat ON.

Considerations

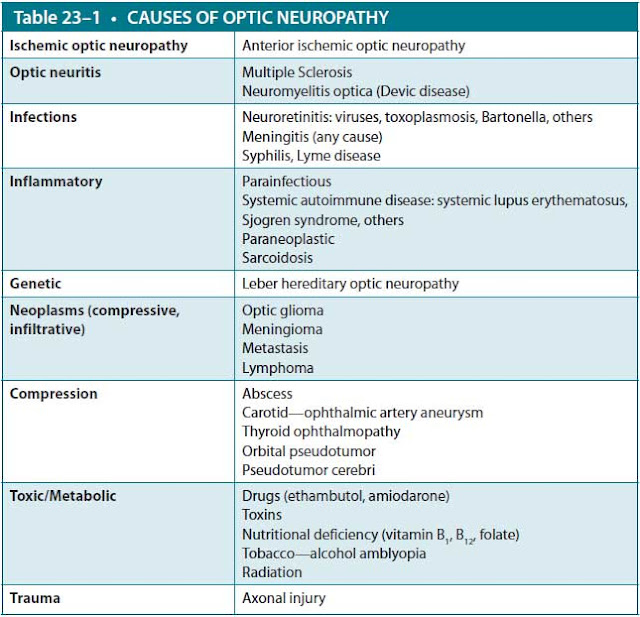

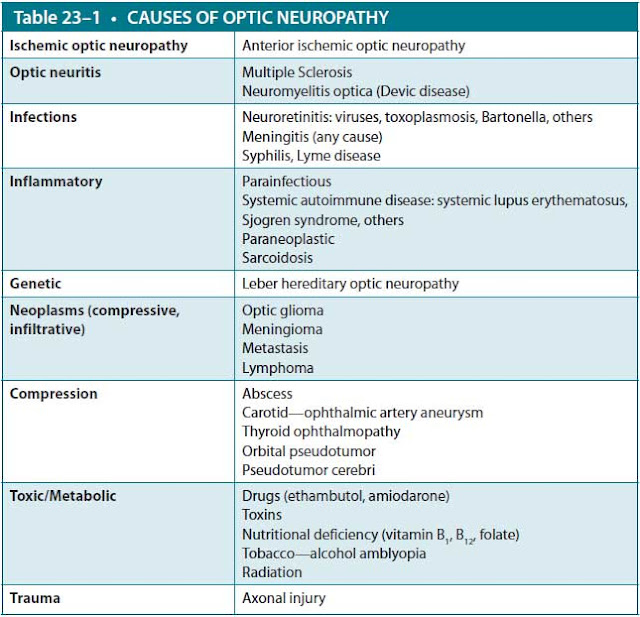

This case is typical for ON, which is an inflammatory, demyelinating condition that causes acute, usually monocular, visual loss. It may be associated with a variety of systemic autoimmune disorders, but with typical ON the most common association is MS. ON is the presenting feature of MS in 20% of patients and occurs in 50% of MS patients at some time during the course of their illness. Most cases of acute demyelinating ON occur in women and typically develop in patients between the ages of 20 and 45. Recovery begins within several weeks of onset of symptoms, and approximately 90% of patients experience a good visual recovery. Some patients have residual deficits in contrast sensitivity, color vision, depth perception, light brightness, visual acuity, or visual field. The patient in this case requires careful neurologic and ophthalmic assessment. Brain imaging and lumbar puncture (LP) for assessment of possible demyelinating disease may be necessary. In contrast to this case, in a young child presenting with these signs and symptoms, infectious and postinfectious causes of optic nerve impairment should be considered as alternatives to ON, while in an older patient (>45 years), ischemic optic neuropathy (eg, due to diabetes mellitus or giant cell arteritis) is a more likely diagnosis than ON. The differential diagnosis of inflammatory optic neuropathy is summarized in Table 23–1.

(Data from UpToDate: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/optic-neuritis-pathophysiology-clinical-features-and- diagnosis.)

APPROACH TO:

Optic Neuritis

DEFINITIONS

SCOTOMA: An isolated area of diminished vision within the visual field.

RELATIVE AFFERENT PUPILLARY DEFECT: When one eye has decreased afferent function relative to the other, the pupil will not constrict as well in response to direct light stimulus. This is demonstrated by shining a light alternately in one eye and then the other (“swinging flashlight test”). When the light is directed into the normal eye, both pupils constrict normally. When the light is then directed into the affected eye, the pupils will appear to dilate instead of constricting. The consensual responses should be intact in both eyes because the efferent pathways are not affected (Figure 23–1).

Figure 23–1. Swinging flashlight test for afferent pupillary defect.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The annual incidence of unilateral ON is approximately 1 to 5 per 100,000. ON is seen most commonly in Caucasians (85% of patients) and in women (77% of patients). Rates are greater at higher latitudes, during spring, and in patients of northern European decent. The onset is usually between 20 and 45 years, with a mean age of 32.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The pathophysiology of typical ON is inflammation and demyelination of the optic nerve. It is believed that the demyelination in ON is immune-mediated, but the specific mechanism and target antigen(s) are unknown. Systemic T-cell activation is identified at symptom onset and precedes changes in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Activated peripheral T cells migrate across the blood-brain barrier and release cytokines and other inflammatory mediators, causing acute demyelination and ultimately resulting in neuronal cell death and axonal degeneration. Inflammatory demyelination is the pathologic hallmark of MS, but after the acute event, axonal damage leads to axonal loss and irreversible neurologic impairment.

CLINICAL APPROACH

Clinical Presentation

ON is usually monocular in its clinical presentation. Bilateral optic neuropathy is more common in children but rare in adults. If symptoms occur in both eyes, either simultaneously or in rapid succession, this may indicate an alternative case of ON. The most common symptoms are pain and vision loss. Over 90% of ON patients complain of eye pain. The periorbital or retrobulbar pain may start 1 to 2 weeks before the vision loss or coincide with the change in vision. The patients often report that the pain is dull and aching in quality and is exacerbated by eye movement. Vision loss typically develops over a period of hours to days, peaking within 1 to 2 weeks. Continued deterioration after that time suggests an alternative diagnosis. Almost all types of visual field defects have been seen in patients with ON, but central scotoma seems to be the most common defect. Visual loss may also include loss of acuity, contrast sensitivity, or dyschromatopsia (color vision defects). Patients may also report positive visual phenomena such as flashes of light or floaters.

On clinical examination, unilateral vision loss should be associated with a relative afferent pupillary defect. Dilated fundoscopic examination findings can be divided into two categories:

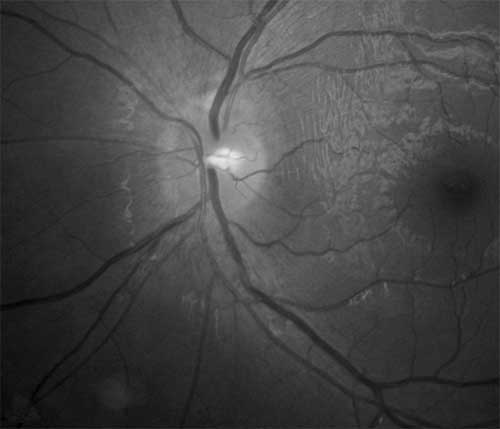

- Papillitis—Anterior ON is defined by swelling of the optic disc. It is seen in one-third of patients with ON. Figure 23–2 shows papillitis with hyperemia and swelling of the disc with blurring of disk margins. If a patient also has macular exudates giving the appearance of “macular star,” the diagnosis is neuroretinitis and much more common in infectious etiologies.

- Retrobulbar neuritis—The optic disc appears normal because the inflammation is located in the optic nerve after it exits the eye. Two-thirds of ON patients have a normal fundoscopic examination. The optic disc will also appear normal in perineuritis, which is inflammation of the optic nerve sheath rather than the nerve itself. This is more common in infectious processes.

Figure 23–2. Papillitis with hyperemia and swelling of the disc in a patient with left optic neuritis. (Reproduced, with permission, from Andrew G. Lee, MD.)

Recovery should begin within several weeks. Continued progression of symptoms after 2 weeks or lack of improvement after 8 weeks suggests an alternative diagnosis. Even after clinical recovery, signs of ON can persist. Over 90% of patients will have good visual recovery, meaning visual acuity of 20/40 or better. However, they may continue to have residual subjective and measurable defects. After the attack, optic atrophy can be seen on fundoscopic examination, especially in the temporal quadrant. Temporary exacerbations of visual problems in patients can occur with increased body temperature (Uhthoff phenomenon). Hot showers and exercise are classic precipitants. In the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial (ONTT), recurrent ON occurred at a rate of 35% at 10 years after the first attack, with MS patients at the highest risk. It may occur in the same eye or the contralateral eye.

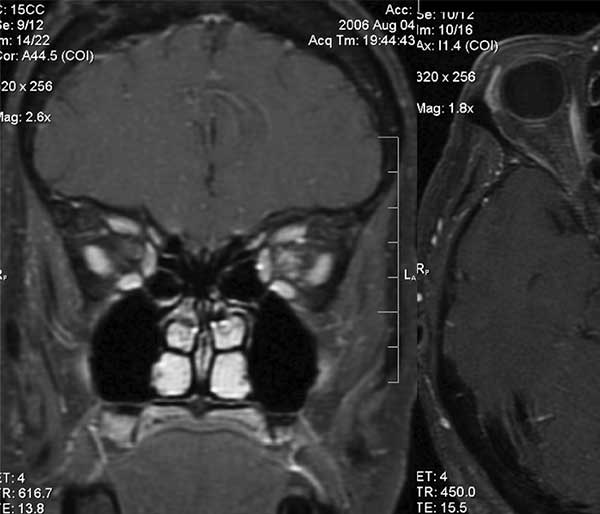

Diagnosis

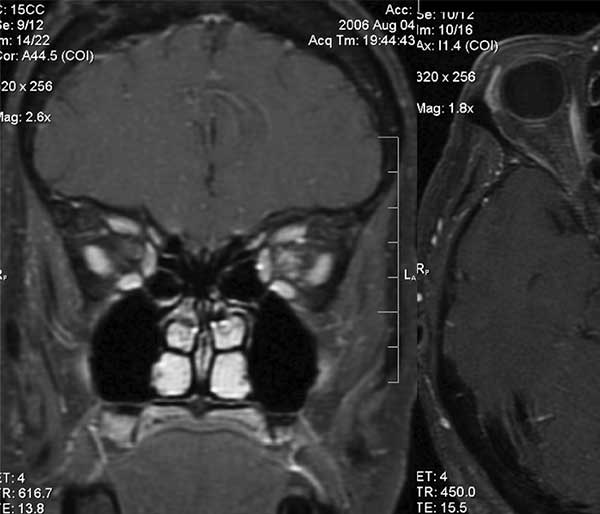

In general, ON is a clinical diagnosis based on history and examination findings. Because important findings on fundoscopic examination help differentiate typical from atypical cases of ON, an ophthalmologic examination should be considered an essential feature of the clinical evaluation. Patients with typical ON do not require further testing for diagnostic purposes, but one may consider a basic screening evaluation with blood studies such as syphilis serology, inflammatory markers, serum chemistries, or complete blood count if the patient has any additional symptoms. MRI with gadolinium contrast shows contrast enhancement of the optic nerve in about 95% of cases (Figure 23–3). MRI of the brain with and without contrast is performed to assess for additional signs of demyelinating disease, which can influence both the prognosis and the long-term treatment. At the final 15-year follow-up of the ONTT, patients with an abnormal baseline MRI had a much higher risk of developing MS compared to those with a normal MRI (72% vs 25%). It is a common practice to start disease-modifying therapy after an initial attack of ON if the MRI is concerning for MS, as this has been shown to delay the onset of a second attack. In atypical cases (eg, prolonged or severe pain, lack of visual recovery, atypical visual field loss, evidence of orbital inflammation), MRI is used to further characterize and to exclude other disease processes.

Figure 23–3. T1-weighted MRI showing gadolinium enhancement of the left optic nerve.

(Reproduced, with permission, from Majdi Radaideh, MD.)

CSF analysis is not necessary in patients with typical demyelinating ON. In the ONTT, only the presence of oligoclonal bands correlated with later development of MS, and an abnormal baseline MRI was a better predictor of MS. When performed, CSF analysis for cell count, protein, immunoglobulin G (IgG) index, and oligoclonal banding might be useful for supporting a clinical diagnosis of MS in patients with typical ON. Patients with atypical ON may require an LP to exclude an alternative etiology for an optic neuropathy.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a noninvasive imaging study performed in the ophthalmology clinic. It may show disc edema in the acute attack and can be followed over time after the attack to assess the extent of atrophy in the retinal nerve fiber layer. Visual-evoked potentials classically show delay of the P100 waveform in demyelinating lesions of the optic nerve but are not required to make the diagnosis.

Treatment

ON is treated with intravenous corticosteroids, which hasten recovery by several weeks but have no effect on long-term visual outcomes. Although corticosteroids have no effect on recurrence of ON in the affected eye, studies suggest that steroids decrease the risk of developing clinical MS in the first 2 years following treatment in patients who have abnormalities on their MRI at the onset of their visual loss. Treatment with oral prednisone at standard doses was actually associated with an increased recurrence rate of ON at 2 years. While the reason for this finding is unclear, oral prednisone therapy is avoided in acute ON. Many of the inflammatory optic neuropathies that mimic ON are also steroid-responsive. In patients without response to steroid therapy, there is some evidence to suggest plasmapheresis could improve visual outcomes. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) has not been proven to have a beneficial effect. Decision to treat typical ON is based on severity of symptoms and medical comorbidities. Since treatment will only serve to hasten recovery time, one must consider the risks and benefits of intravenous steroid therapy in the individual patient.

CASE CORRELATION

- See also Case 24 (Multiple Sclerosis)

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

23.1 A 72-year-old man with history of arthritis, especially in his shoulders, complains of acute loss of vision to his right eye and new-onset pain in the periorbital area lateral to his eye. The examination suggests ON. Which of the following conditions is most likely to be associated?

A. Giant cell arteritis

B. MS

C. Wegener granulomatosis

D. Neuromyelitis optica

23.2 A 24-year-old man is noted to have ON and also weakness. A tentative diagnosis of MS is made. Which of the following is associated with an increased risk of developing MS?

A. One lesion on MRI of the brain

B. CSF with mildly elevated white blood cell count

C. History of ocular trauma

D. Recent history of vaccination

23.3 Which of the following would be considered atypical for ON?

A. Pain with eye movement

B. Decreased color vision

C. Simultaneous involvement of both eyes

D. Complete loss of vision in the affected eye

23.4 Which of the following statements is true?

A. An MRI of the brain is required to diagnose ON.

B. Intravenous steroids are the standard of care because these help improve the visual outcomes of the patients.

C. The first symptom is usually vision loss, followed by eye pain soon after.

D. While most patients can be expected to make a good visual recovery even without treatment, long-term follow-up will usually reveal optic atrophy.

ANSWERS

23.1 A. Giant cell arteritis can be associated with ON in older patients. Patients may have new-onset headaches, jaw claudication, and tenderness on palpation of the temple. Polymyalgia rheumatica is strongly associated with giant cell arteritis, so it is important to ask patients about proximal joint pain. Wegener granulomatosis is more common in men but less likely at this age. Neuromyelitis optica can occur in older individuals but is very rare and usually affects individuals between ages 40 and 50. MS would be lower on the differential in this patient due to the age, sex, and associated new-onset headache.

23.2 A. ON patients with an abnormal MRI have a much higher risk of developing MS than those who had a normal MRI. Abnormal CSF studies, particularly the presence of oligoclonal bands, are also associated with an increased risk of disease. However, no CSF study is diagnostic of disease, and the MRI is considered more reliable than CSF oligoclonal bands in predicting future MS risk.

23.3 C. Bilateral ON, either simultaneously or in rapid succession, should suggest another etiology than typical ON, possibly neuromyelitis optica. Typical ON can have varied visual loss, involving color vision, contrast sensitivity, and visual acuity. Even patients with severe visual deficits can make a good recovery with typical ON.

23.4 D. Patients with a prior history of ON have optic atrophy, and many patients will continue to report vision abnormalities. An MRI is not required to make the diagnosis but is recommended to determine the risk for further demyelinating events. Intravenous steroids hasten the recovery but do not change the ultimate outcome. Over 90% of patients report eye pain, and it can start up to 1 to 2 weeks before the vision loss.

CLINICAL PEARLS

|

▶ ON typically presents as an acute

monocular compromise of vision associated with eye pain, especially with eye

movement.

▶ The standard treatment is IV

methylprednisolone, but this has only been shown to hasten recovery and does

not change the long-term visual outcomes.

▶ Over 90% of patients with typical ON

make a good visual recovery.

▶ An MRI scan should be obtained in a

patient with ON to assess for risk of future MS. An abnormal MRI at the time

of the ON attack significantly increases the chance of developing MS in the

future (72% of patients at 15 years).

▶ In patients with bilateral ON or poor

visual recovery, consider neuromyelitis optica in the differential diagnosis.

There are also many other inflammatory optic neuropathies to consider based

on the history and examination findings.

|

REFERENCES

Balcer LJ. Clinical practice. Optic neuritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1273-1280.

Bermel RA, Balcer LJ. Optic neuritis and the evaluation of visual impairment in multiple sclerosis. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2013;19(4):1074-1086.

Brazis PW, Lee AG. Optic neuritis. In: Evans RW, ed. Saunders Manual of Neurologic Practice. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2003:371-374.

Brazis PW, Lee AG. Optic neuropathy. In: Evans RW, ed. Saunders Manual of Neurologic Practice. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2003:375-383.

Costello F. Inflammatory optic neuropathies. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2014;20(4):816-837.

Katz Sand IB, Lublin FD. Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2013;19(4):922-943.

Pau D, Al Zubidi N, Yalamanchili S, Plant GT, Lee AG. Optic neuritis. Eye. 2011;25:833-842.

Toosy AT, Mason DF, Miller DH. Optic neuritis. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(1):83-99.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.