Shoulder Dystocia Case File

Eugene C. Toy, MD, Patti Jayne Ross, MD, Benton Baker III, MD, John C. Jennings, MD

CASE 4

A 25-year-old G2P1 woman is delivering at 42 weeks’ gestation. The woman is noted to have a body mass index of 42 kg/m2. The fetal weight clinically appears to be about 3700 g. After a 4-hour first stage of labor and a 2-hour second stage of labor, the fetal head delivers but is noted to be retracted back toward the patient’s introitus. The fetal shoulders do not deliver, even with maternal pushing.

» What is your next step in management?

» What is a likely complication that can occur because of this situation?

» What maternal condition would most likely put the patient at risk for this condition?

ANSWER TO CASE 3:

Shoulder Dystocia

Summary: A 25-year-old obese G2P1 woman is delivering at 42 weeks’ gestation; the fetus appears clinically to be 3700 g (average weight). After a 4-hour first stage of labor and a 2-hour second stage of labor, the head delivers but the shoulders do not easily deliver.

- Next step in management: McRoberts maneuver (hyperflexion of the maternal hips onto the maternal abdomen and/ or suprapubic pressure).

- Likely complication: A likely maternal complication is postpartum hemorrhage; a common neonatal complication is a brachial plexus injury such as an Erb palsy.

- Maternal condition: Gestational diabetes, which increases the fetal weight on the shoulders and abdomen.

ANALYSIS

Objectives

- Understand the risk factors for shoulder dystocia.

- Understand that shoulder dystocia is an obstetric emergency, and be familiar with the initial maneuvers used to manage this condition.

- Know the neonatal complications that can occur with shoulder dystocia.

Considerations

The patient is multiparous and obese, both of which are risk factors although not the strongest risk factors, for shoulder dystocia. The prenatal risk factors in order of significance are (1) prior shoulder dystocia, (2) fetal macrosomia, and (3) maternal gestational diabetes. There is no indication of gestational diabetes in this patient. The patient is post-term at 42 weeks, which increases the likelihood of fetal macrosomia. The patient’s prolonged second stage of labor (upper limits for a multiparous patient is 1 hour without and 2 hours with epidural analgesia) may be a nonspecific indicator of impending shoulder dystocia. Nevertheless, the diagnosis is straightforward, in that the fetal shoulders are described as not easily delivering. The fetal head is retracted back toward the maternal introitus, the “turtle sign.” Because most shoulder dystocia events are unpredictable, as in this case, the clinician must be proficient in the management of this entity, particularly because of the potential for fetal injury.

APPROACH TO:

Shoulder Dystocia

DEFINITIONS

SHOULDER DYSTOCIA: Inability of the fetal shoulders to deliver spontaneously, usually due to the impaction of the anterior shoulder behind the maternal symphysis pubis.

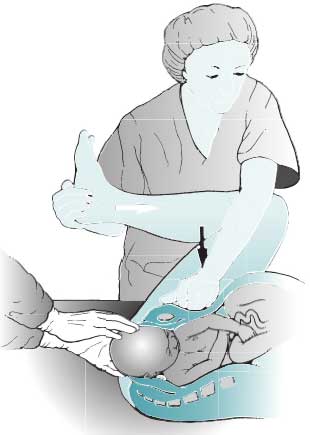

McROBERTS MANEUVER: The maternal thighs are sharply flexed against the maternal abdomen to straighten the sacrum relative to the lumbar spine and rotate the symphysis pubis anteriorly toward the maternal head (Figure 4– 1).

SUPRAPUBIC PRESSURE: The operator’s hand is used to push on the suprapubic region in a downward or lateral direction in an effort to push the fetal shoulder into an oblique plane and from behind the symphysis pubis.

ERB PALSY: A brachial plexus injury involving the C5–C6 nerve roots, which may result from the downward traction of the anterior shoulder; the baby usually has weakness of the deltoid and infraspinatus muscles as well as the flexor muscles of the forearm. The arm often hangs limply by the side and is internally rotated.

Figure 4–1. Maneuvers for shoulder dystocia. The McRoberts maneuver involves flexing the maternal

thighs against the abdomen. Suprapubic pressure attempts to push the fetal shoulders into an

oblique plane. (Reproduced with permission from Cunningham FG, et al. Williams Obstetrics. 22nd ed.

New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005:515.)

CLINICAL APPROACH

Because of the unpredictability and urgency of shoulder dystocia, the clinician should rehearse its management and be ready when the situation is encountered. Shoulder dystocia should be suspected with prior history of shoulder dystocia, fetal macrosomia, gestational diabetes, excessive weight gain (> 35 lbs) in pregnancy, maternal obesity, and prolonged second stage of labor. With gestational diabetes, the elevated fetal insulin levels are associated with increased weight centrally (shoulders and abdomen). However, it must be noted that almost one-half of all cases occur in babies weighing less than 4000 g, and shoulder dystocia is frequently unsuspected. Significant fetal hypoxia may occur with undue delay from the delivery of the head to the body. Moreover, excessive traction on the fetal head may lead to a brachial plexus injury to the baby. It should be recognized that brachial plexus injury can occur with vaginal delivery not associated with shoulder dystocia, or even with cesarean delivery. Shoulder dystocia is not resolved with more traction, but by maneuvers to relieve the impaction of the anterior shoulder (Table 4– 1).

The diagnosis is suspected when external rotation of the fetal head is difficult, and the fetal head may retract back toward the maternal introitus, the “turtle sign.” The diagnosis is confirmed when the baby fails to deliver with normal symmetric traction. The first actions of the fetus are nonmanipulative, such as the McRoberts maneuver and suprapubic pressure. Fortunately, the majority of shoulder dystocia cases are relieved with these nonmanipulative actions. Fundal pressure should be avoided when shoulder dystocia is diagnosed because of the increased associated neonatal injury. Other maneuvers include the Wood’s corkscrew (progressively rotating the posterior shoulder in 180° in a corkscrew fashion), delivery of the posterior arm, and the Z avanelli maneuver (cephalic replacement with immediate cesarean section). Maternal complications of shoulder dystocia include both postpartum hemorrhage and vaginal/ perineal lacerations. Fetal complications include brachial plexus injuries, clavicle fractures, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, and even death.

One area of controversy is the practice of cesarean delivery in certain circumstances in an attempt to avoid shoulder dystocia; indications include macrosomia diagnosed on ultrasound, particularly with maternal gestational diabetes. Because of the imprecision of estimated fetal weights and prediction of shoulder dystocia, there is no uniform agreement regarding this practice. Operative vaginal delivery,

such as vacuum- or forceps-assisted deliveries in the face of possible fetal macrosomia,

may possibly increase the risk of shoulder dystocia.

|

Table 4–1 • COMMON MANEUVERS

FOR TREATMENT OF SHOULDER DYSTOCIA

|

|

McRoberts maneuver

(hyperflex maternal thighs)

Suprapubic pressure

Wood’s corkscrew

maneuver

Delivery of the

posterior arm

Zavanelli maneuver

(cephalic replacement and cesarean) |

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

4.1 A 25-year-old G1P0 woman delivers a 4000 g infant, and encounters a shoulder dystocia. Which of the following is a risk factor for this condition?

A. Maternal gestational diabetesB. Fetal hydrocephalusC. Fetal prematurityD. Precipitous (fast) labor

4.2 A 30-year-old woman is noted to be in active labor at 40 weeks’ gestation. Delivery of the fetal head occurs, but the fetal shoulders do not deliver with the normal traction. The fetal head is retracted toward the maternal introitus. Which of the following is a useful maneuver for this situation?

A. Internal podalic versionB. Suprapubic pressureC. Fundal pressureD. Intentional fracture of the fetal humerusE. Delivery of the anterior arm

4.3 A 3800 g male infant is delivered vaginally. A shoulder dystocia was encountered. If a neonatal injury is suspected, what is the likely finding in the infant?

A. Arm that is fixed and flexed and hypertonicB. Arm that is at its side and internally rotatedC. Clavicle fractureD. Depressed skull fractureE. Dislocated elbow

Match the following mechanisms (A-E) to the stated maneuver (4.4-4.6):

A. Anterior rotation of the symphysis pubisB. Decreases the fetal bony diameter from shoulder– shoulder to shoulder– axillaC. Fracture of the clavicleD. Displaces the fetal shoulder axis from anterior– posterior to obliqueE. Separates the maternal symphysis pubis

4.4 The clinician performs a delivery of the posterior fetal arm.

4.5 The McRoberts maneuver is utilized.

4.6 The nurse is instructed to apply the suprapubic pressure maneuver.

ANSWERS

4.1 A. Gestational diabetes is a risk factor because the fetal shoulders and abdomen are disproportionately bigger than the head, therefore the head may pass through with no problems, yet it is quite difficult to deliver the anterior shoulder since it is lodged behind the maternal symphysis pubis. The McRoberts maneuver and application of suprapubic pressure are two techniques that attempt to relieve the impaction of the anterior shoulder. Unlike gestational diabetes, the complication with hydrocephalus is that the fetal head is greater than the body. The head itself may have a difficult time passing through the pelvis, but if it does pass, the shoulders would have no problem passing through since their width would be smaller than the width of the fetal head. The premature fetus typically has a well-proportioned body, but is overall smaller in size than the average-sized baby. No part of a premature fetus’ body should typically get impacted anywhere along the birth canal. With precipitous labor, there is a decreased chance that a shoulder dystocia will occur, whereas a prolonged second stage of labor should raise suspicion that a dystocia is present.

4.2 B. The patient in this question has shoulder dystocia. The McRoberts maneuver or suprapubic pressure is generally the first maneuver used. The McRoberts maneuver involves sharply flexing the maternal thighs against the maternal abdomen to straighten the sacrum relative to the lumbar spine and rotate the symphysis pubis anteriorly toward the maternal head. Applying suprapubic pressure, or pushing on the suprapubic region, relieves the fetal shoulder from being impacted behind the symphysis pubis. The internal podalic version is an obstetric procedure in which the fetus, typically in a transverse position, is rotated inside the womb to where the feet or a foot is the presenting part during labor and delivery. This method would not be applicable in this situation because the fetus is presenting in the proper cephalic position. Fracturing of the fetal humerus is a complication that can occur with shoulder dystocia if one of the fetal arms is pulled or tugged on too forcefully. Attempting to deliver the anterior shoulder in the setting of shoulder dystocia can result in a brachial plexus injury involving the C5–C6 nerve roots. As a result, the baby could have weakness of the deltoid and infraspinatus muscles as well as the flexor muscles of the forearm (Erb palsy/ ”Waiter’s tip”).

4.3 B. An Erb palsy is the most common injury of the neonate in a shoulder dystocia. The arm is typically limp and at its side with the arm internally rotated. If the palsy is severe, then the infant may not be able to move its fingers. Eighty percent of the time, brachial plexus injuries will improve with physical therapy. However, if the nerve roots are avulsed rather than simply injured, the neuropathy usually will not resolve.

4.4 B. With delivery of the posterior arm, the shoulder girdle diameter is reduced from shoulder-to-shoulder to shoulder-to-axilla, which usually allows the fetus to deliver. The danger with this maneuver is potential injury to the infant’s humerus, such as a fracture. Fortunately, it is typically a simple fracture of the midshaft which heals well.

4.5 A. The McRoberts maneuver causes anterior rotation of the symphysis pubis and flattening of the lumbar spine. This relieves the anterior shoulder from impaction and allows for delivery of the fetus. Separating the symphysis pubis is not associated with any kind of mechanism or maneuver for relieving shoulder dystocia. Fracturing the humerus is never indicated either, and may also lead to brachial plexus injury.

4.6 D. The rationale of suprapubic pressure is to move the fetal shoulders from the anteroposterior to an oblique plane, allowing the shoulder to slip out from under the symphysis pubis. Applying fundal pressure would only supply a greater force of the fetal shoulder against the symphysis pubis and possibly cause a more complex and serious situation such as brachial plexus injury to the fetus.

CLINICAL PEARLS

|

» Shoulder dystocia

cannot be predicted nor prevented in the majority of cases.

» The biggest risk factor

for shoulder dystocia is fetal macrosomia, particularly in a woman who has

gestational diabetes.

» The estimation of fetal

weight is most often inaccurate, as is the diagnosis of macrosomia.

» The most common injury

to the neonate in a shoulder dystocia is brachial plexus injury, such as

Erb palsy.

» The first actions for

shoulder dystocia are generally the McRoberts maneuver or suprapubic

pressure.

» Fundal pressure should

not be used once shoulder dystocia is encountered. |

REFERENCES

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Shoulder dystocia. ACOG Practice Bulletin 40. Washington, DC; 2002. (Reaffirmed 2015.)

Bashore RA, Ogunyemi D, Hayashi RH. Uterine contractility and dystocia. In: H acker NF, Gambone JC, Hobel CJ, eds. Essentials of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2009:139-145.

Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, et al. Vaginal delivery—shoulder dystocia. In: Williams Obstetrics. 24th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; Chap. 27, 2014.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.