Labor (Latent Phase) Case File

Eugene C. Toy, MD, Patti Jayne Ross, MD, Benton Baker III, MD, John C. Jennings, MD

CASE 1

A 26-year-old G1P0 woman at 39 weeks’ gestation is admitted to the hospital in labor. She is noted to have uterine contractions every 2 to 3 minutes. Her antepartum history is significant for a nonimmune rubella status. On examination, her blood pressure (BP) is 110/70 mm Hg and heart rate (HR) is 80 beats per minute (bpm). The estimated fetal weight is 7 lbs. On pelvic examination, she has been noted to have a change in cervical examinations from 4-cm dilation to 5-cm over the last 2 hours. The pelvis is assessed to be adequate on digital examination.

» What is your next step in the management of this patient?

ANSWER TO CASE 1:

Labor (Latent Phase)

Summary: A 26-year-old G1P0 woman at term with an adequate pelvis on clinical pelvimetry, nonimmune rubella status, is in labor. Her cervix has changed from 4- to 5-cm dilation over 2 hours with uterine contractions noted every 2 to 3 minutes.

- Next step in management: Continue to observe the labor.

ANALYSIS

Objectives

- Know the normal labor parameters in the latent and active phase for nulliparous and multiparous patients.

- Be familiar with the management of common labor abnormalities and know that normal labor does not require intervention.

- Know that rubella vaccination, as a live-attenuated preparation, should not be administered during pregnancy.

Considerations

This 26-year-old G1P0 woman is at term (defined as between 37 and 42 completed weeks’ gestational age). She has not yet reached active phase of labor (generally about 6 cm of dilation) and her cervix has changed from 4 to 5 cm over 2 hours; her contractions are every 2 to 3 minutes. Previously, active phase was defined as beyond 4 cm of cervical dilation; however, recent studies have shown that active phase cannot be reliably defined until 6 cm of dilation. In the latent phase of labor, there is no need for intervention; however, if the progress is prolonged or uterine contractions are inadequate, oxytocin is an option. The uterine contraction pattern appears to be every 2 to 3 minutes. Because she has had normal labor, the appropriate management is to observe her course without intervention. The clinical pelvimetry is accomplished by digital palpation of the pelvic bones (passageway). This patient’s pelvis was judged on physical examination to be adequate. Unfortunately, this estimation is not very precise, and in clinical practice, the clinician would generally observe the labor of a nulliparous patient. Finally, the nonimmune rubella status should alert the practitioner to immunize for rubella during the postpartum time (since the rubella vaccine is live attenuated and is contraindicated during pregnancy).

APPROACH TO:

Labor Evaluation

CLINICAL APPROACH TO LABOR

Normal and Abnormal Labor

The assessment of labor is based on cervical change versus time (Table 1– 1). Normal labor should be expectantly managed. When a labor abnormality is diagnosed, the three Ps should be evaluated (powers, passenger, and pelvis). When inadequate “powers” are thought to be the etiology, then oxytocin may be initiated to augment the uterine contraction strength and/ or frequency. When the latent phase exceeds the upper limits of normal, then it is called a prolonged latent phase. When the cervix has exceeded 6 cm, particularly with near-complete effacement, then the active phase has been reached. Recent studies have shown that as long as there is continued progress of labor in the active phase, in the absence of complications, the labor should be observed. No cervical dilation for 4 hours in the active phase with rupture of membranes (ROM) and adequate contractions is called arrest of active phase.

|

Table 1–1 • NORMAL LABOR PARAMETERS

|

|

|

Nullipara (Lower

Limits of Normal)

|

Multipara (Lower

Limits of Normal)

|

|

Latent phase (dilation <6 cm)

|

≤18-20 h

|

≤14 h

|

|

Active phase

|

Continued progress

|

Continued progress

|

|

Second stage of

labor (complete dilation to expulsion of

infant)

|

≤3 h

≤4 h if epidural

|

≤2 h

≤3 h if epidural

|

|

Third stage of

labor

|

≤30 min

|

≤30 min

|

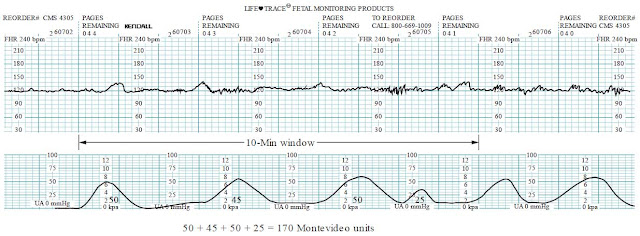

When there is cephalopelvic disproportion, where the pelvis is thought to be too small for the fetus (either due to an abnormal pelvis or an excessively large baby), then cesarean delivery must be considered. When the “powers” are thought to be the factor, then intravenous (IV) oxytocin may be initiated via a dilute titration. Clinically, adequate uterine contractions are defined as contractions every 2 to 3 minutes, firm on palpation, and lasting for at least 40 to 60 seconds (Figure 1– 1). Many clinicians choose to use internal uterine catheters to evaluate the adequacy of the powers, a practice that may reduce cesareans. One common assessment tool is to examine a 10-minute window and add each contraction’s rise above baseline (each mm Hg rise is called a Montevideo unit). A calculation that meets or exceeds 200 Montevideo units is commonly accepted as an adequate uterine contraction pattern (Figure 1– 2).

Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring

Fetal heart rate assessment can help to assess the fetal status. A normal baseline between 110 and 160 bpm, with accelerations, and variability are indicative of a normal well-oxygenated fetus. Fetal tachycardia can occur due to a variety of disorders such as maternal fever. Fetal bradycardia, if profound and prolonged, necessitates intervention. The most common decelerations are variable, caused by cord compression. If these are intermittent with abrupt return to baseline, then they can be observed. Early decelerations, caused by fetal head compression, are benign. Late decelerations are “offset” from the uterine contraction with their onset after the onset of the contraction, the nadir following the contraction peak, and the return to baseline following the contraction resolution. Late decelerations suggest fetal hypoxia, and if recurrent (>50% of uterine contractions), can indicate fetal acidemia. When late decelerations occur together with decreased variability, then acidosis is strongly suspected (see Figure 1– 3).

- Category I is reassuring—normal baseline and variability, no late or variable decelerations.

- Category II bears watching—may have some aspect that is concerning but not ominous (eg, fetal tachycardia without decelerations).

- Category III is ominous and indicates a high likelihood of severe fetal hypoxia or acidosis—examples include absent baseline variability with recurrent late or variable decelerations or bradycardia, or sinusoidal heart rate pattern (this requires prompt delivery if no improvement).

aAdequa te contra ctions gene rally >200 Monte video units or clinically contractions every 2-3 min,

firm, lasting 40-60 sec.

Figure 1–1. Algorithm for management of labor.

Figure 1–2. Calculating Montevideo units. Montevideo units are calculated by the sum of the amplitudes (in mm Hg) above baseline of the uterine contractions within a 10-minute window.

Figure 1–3. Fetal heart rate decelerations. (A) Early deceleration—note arrow shows deceleration is gradual and a mirror image to the uterine contraction. (B) Late deceleration—note arrow shows deceleration nadir is after the peak of the uterine contraction. (C) Variable deceleration—note arrow shows the deceleration is abrupt in its decline and resolution.

Figure 1–3.

Figure 1–3.

Safe Prevention of the Primary Cesarean Delivery

In 2011, one in three deliveries in the US were by cesarean; this rate has steadily increased over the past decades without any significant improvement in maternal or fetal outcome. The reasons in order of frequency are labor dystocia (34%), abnormal fetal heart rate pattern (23%), fetal malpresentation (17%), multiple gestation (7%), and suspected fetal macrosomia (4%). As compared to vaginal delivery, cesarean has a higher overall severe morbidity or mortality rate, and a 3.5-fold increased risk of mortality. To safely reduce the number of primary vertex presenting cesareans, an evidenced based approach should be used for the reasons for abdominal deliveries: labor arrest and nonreassuring FHR pattern comprise 57% of causes (See Table 1– 2).

Management of FHR Tracing

Category I tracings are reassuring and do not need intervention. Category III tracings are abnormal and require prompt intervention; if prompt intrauterine resuscitative maneuvers are not curative, imminent delivery is prudent because these tracings are associated with low pH, hypoxia, encephalopathy, and cerebral palsy.

Most FHR tracings are category II, which can span from a reassuring FHR tracing: normal baseline, moderate variability, accelerations, and mild variable decelerations versus a tracing that is worrisome, such as a tracing showing minimal variability and intermittent deep variable decelerations. Scalp stimulation inducing an acceleration highly correlates to a normal umbilical cord pH (≥7.20). Prolonged FHR decelerations (lasting > 2 minutes but < 10 minutes) often require intervention (see Table 1– 3):

|

Table

1–2 • AFTER REVIEW OF MANY STUDIES, THE CONSORTIUM OF SAFE LABOR MADE THE FOLLOWING RECOMMENDATIONS

|

|

- The traditional

definitions of normal latent labor may be kept (20 hours for nulliparous, 14 hours for multiparous),

but prolonged latent phase (in the absence of clear cephalopelvic disproportion [CPD]) is

not an indication for cesarean.

- Slow but progressive

labor in the first stage of labor (onset to complete dilation) should not be an

indication for cesarean.

- Active phase is

defined as cervical dilation ≥6 cm.

- Cesarean for active

phase arrest is reserved for women at or beyond 6 cm with ruptured membranes, who fail to

progress despite 4 hours of

adequate uterine activity, or ≥ 6 hours of oxytocin with inadequate uterine activityand no

cervical change.

- Arrest in the second

stage of labor requires at least 2 hours pushing in multiparous and 3 hours pushing in

nulliparous (longer duration with epidural or malposition [ie, occiput posterior, OP] as long

as progress is documented).

- Amnioinfusion for repetitive variable

decelerations may safely reduce the rate of cesarean.

- Scalp stimulation

can help to assess fetal acid–base status when an abnormal or indeterminate (formerly

reassuring) FHR pattern (such as minimal variability) is present.

- External cephalic

version should be offered to women after 36 weeks with malpresentation.

- Cesarean to avoid

birth trauma/shoulder dystocia should be limited to estimated fetal weight of

≥5000 g in a nondiabetic woman and 4500 g in a diabetic woman.

- For persistent

occiput posterior or occiput transverse (OT) head positions can be managed by

manual rotation of the fetal head, or forceps (but forceps are not as often

used now).

|

|

Table 1–3 • INTERVENTIONS FOR PROLONGED DECELERATIONS

|

|

Etiology

|

Finding

|

Intervention

|

|

Tachysystole

|

Uterine contractions

>5 /10 min averaged over 30 min

|

Decrease or stop

oxytocin, or

administer beta-mimetic

agent

|

|

Hypotension (such

as

due to regional anesthesia, ie,

epidural)

|

Low BP following

epidural or spinal

|

IV fluid bolus, or

administer

vasopressor agent such

as

ephedrine

|

|

Rapid cervical

dilation

|

Labor progression especially descent rapid

|

Positional changes, observation

|

|

Umbilical cord

prolapse

|

Vaginal examination

reveals cord through cervix

|

Elevate presenting part

and

emergency cesarean

|

|

Placental

abruption

|

Uterine tenderness,

vaginal

bleeding (may be absent

with concealed abruption)

|

Support BP, stabilize

patient,

consider cesarean if

progressive

|

|

Uterine rupture

|

Hx of prior cesarean

|

Emergency cesarean

|

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

1.1 A 31-year-old G2P1 woman at 39 weeks’ gestation complains of painful uterine contractions that are occurring every 3 to 4 minutes. Her cervix has not changed from 6-cm dilation over 3 hours. Which one of the following management plans is most appropriate?

1.7 A 37-year-old G3P2 woman is at 40 weeks’ gestation and chronic hypertension. She has been induced with Pitocin and her cervix has been at 3 cm for the past 4 hours. Her fetal heart rate pattern is given below. Which of the following is the best management for this patient? (Figure 1– 4)

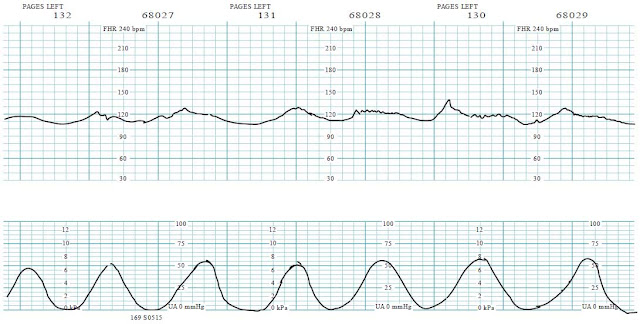

1.8 A 39-year-old G4P2 Ab1 woman is at 37 weeks’ gestation and arrived in active labor. She progressed from 4 to 5 cm over 2 hours. The estimated fetal weight is 7 lb 3 oz, and the pelvis is judged as adequate. The FHR tracing is given below. What is the best next step for this patient? (Figure 1– 5)

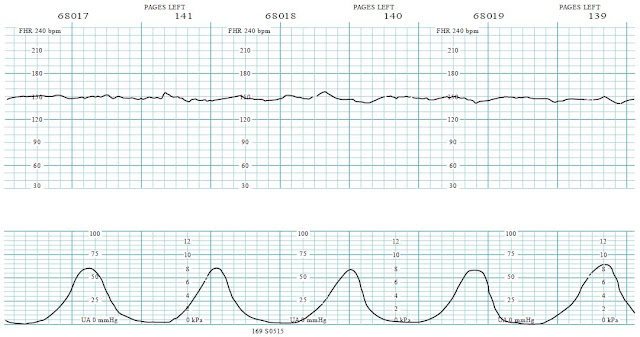

1.9 An 18-year-old G1P0 woman at 39 weeks’ gestation was admitted for labor. She progressed from 4 cm dilation to 6 cm dilation over 2 hours. The FHR tracing is given below. What is your next step in her management? (Figure 1– 6)

1.10 A 25-year-old G2P1001 is noted to have a baseline FHR of 150 bpm with moderate variability. She is noted to have repetitive late decelerations shortly after the placement of an epidural catheter for pain control. Her BP is 90/ 55 mm Hg and HR is 100 bpm. What is the best next step in managing this patient?

ANSWERS

1.1 C. Observation is best. This patient has presumably entered into the active phase (6 cm) but not progressed for 3 hours. Also the uterine contraction pattern does not seem adequate since frequency is only every 3 to 4 minutes. We are not told about status of the membranes. Recent studies have indicated that if all other parameters (fetal heart rate tracing) are normal, then cesarean is reserved for active phase arrest with ROM for 4 hours with adequate contractions, or 6 hours with inadequate contractions. Intravenous oxytocin enhances contraction strength and/ or frequency, but does not affect cervical dilation. Intranasal gonadotropin therapy is not indicated during any phase of labor.

Figure 1–4. FHR tracing (reproduced, with permission, from Eugene C. Toy, MD).

Figure 1–5. FHR tracing (reproduced, with permission, from Eugene C. Toy, MD).

Figure 1–6. FHR tracing (reproduced, with permission, from Eugene C. Toy, MD).

1.2 C. Arrest of descent. A 3-hour second stage of labor still is abnormal, even with epidural analgesia. An anthropoid pelvis, which predisposes to the persistent fetal occiput posterior position, is characterized by a pelvis with an anteroposterior diameter greater than the transverse diameter with prominent ischial spines and a narrow anterior segment. The baby is at “0” station, meaning that the presenting part (in most cases, the bony part of the fetal head) is right at the plane of the ischial spines and not at the pelvic inlet. Station refers to the relationship of the presenting bony part of the fetal head in relation to the ischial spines, and not the pelvic inlet. Engagement refers to the relationship of the widest diameter of the presenting part and its location with reference to the pelvic inlet. Manual rotation of the fetal head may be considered in selected circumstances.

1.3 E. This is normal labor. This patient is <6 cm dilated, so she is still in the latent phase of labor. The upper limits of normal of latent labor are 20 hours for nullipara and 14 hours for multipara.

1.4 C. Bloody show or loss of the cervical mucus plug is often a sign of impending labor. The sticky mucus admixed with blood can differentiate bloody show from antepartum bleeding. Placenta previa, placental abruption, and vasa previa are all associated with antepartum bleeding. A cervical laceration typically occurs during a vaginal delivery. They may be associated with postpartum hemorrhage.

1.5 C. Increased neonatal complications. Delivery <39 weeks’ gestation, such as by induction of labor or scheduled cesarean, is associated with an increased risk of neonatal complications including increased incidence of neonatal intensive care unit admission, respiratory difficulties, sepsis, hyperbilirubinemia, ventilator use, and hospital stay exceeding 5 days. For this reason, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American Academy of Pediatricians (AAP) recommend against delivery < 39 weeks without a medical indication.

1.6 B. Continued observation on oxytocin is the best plan for prolonged latent phase, with the same definitions as per Friedman’s data (20 hours for nulliparous women and 14 hours for multiparous women). Prolonged latent phase should not be a reason for cesarean delivery, and almost always, a patient will reach the active phase of labor. Once a patient has a favorable cervix (generally beyond 2-3 cm, but also taking into account effacement, softness of the cervix and station), cervical ripening with misoprostol or Foley bulb is not helpful. The patient has ruptured membranes (amniotomy) and therefore is not a candidate to be discharged.

1.7 G. Terbutaline may be helpful. This is a uterine contraction pattern of excessive number of contractions or tachysystole. There are seven contractions in the 9-minute window illustrated and late decelerations. The use of a betamimetic agent such as terbulatine will bring about uterine relaxation and hopefully resolve the late decelerations. The tachysystole is likely due to excessive oxytocin. Thus, the oxytocin should also be turned off.

1.8 F. Scalp stimulation may be useful. This patient is in the latent phase of labor. The FHR strip is category II, indeterminate due to the lack of accelerations and minimal variability; the pattern in and of itself is not necessarily alarming, but when the clinical picture is taken as a whole, it may become worrisome. For instance, if the FHR pattern preceding was category I, this may just be a sleep cycle, and bears reevaluation in 10 minutes; however, if this pattern of minimal variability and lack of accelerations persist, fetal hypoxia may be present. A fetal scalp stimulation inducing an acceleration would be reassuring and allow continued observation of this tracing.

1.9 A. Amnioinfusion may help with this pattern. This 18-year-old nulliparous patient is progressing into the active phase of labor. She is having repetitive deep variable decelerations and an amnioinfusion would help to alleviate the cord compression and hopefully, allow for a vaginal delivery. Studies have shown that amnioinfusion for variable decelerations reduces the risk for cesarean.

1.10 C. The vasopressive sympathomimetic agent ephedrine may help. This patient is having late decelerations likely due to the hypotension from the epidural analgesia. IV fluid hydration would be the first course of action, and if unsuccessful, then a vasopressor agent such as ephedrine would be useful; theoretically, ephedrine causes vasoconstriction of the peripheral vasculature and spares the uterine arteries. The corrective actions usually lead to resolution of the late decelerations fairly rapidly. The mechanism of the action of epiduralinduced hypotension is sympathetic blockade leading to vasodilation. Prior to administration of regional anesthesia, a patient typically will receive an IV fluid bolus as a preventive measure.

CLINICAL PEARLS

|

» The normalcy of labor

is determined by assessing the cervical change versus time. Normal

labor should be observed.

» Cesarean delivery (for

labor abnormalities) in the absence of clear cephalopelvic disproportion is

generally reserved for arrest of active phase and ROM with adequate

uterine contractions for at least 4 hours, or inadequate uterine contractions

for at least 6 hours.

» Adequate uterine

contractions is not a precise definition, but is commonly judged as >200

Montevideo units with an internal uterine pressure catheter, or by uterine

contractions every 2 to 3 minutes, firm on palpation, and lasting

at least 40 to 60 seconds.

» In general, latent

labor occurs when the cervix is less than 6 cm dilated and active labor when

the cervix is >6 cm dilated.

» Early decelerations are

mirror images of uterine contractions, caused by fetal head

compressions.

» Variable decelerations

are abrupt in decline and abrupt in resolution and are caused by cord

compression.

» Late decelerations are

gradual in shape and are offset from the uterine contractions, caused by

uteroplacental insufficiency (hypoxia).

» The normal fetal heart rate

baseline is between 110 and 160 bpm.

» Fetal scalp stimulation

inducing an acceleration is reassuring for an umbilical cord pH

>7.20. » Amnioinfusion can be

helpful in the face of repetitive variable decelerations. » Category II FHR

patterns are the most common and have a wide variety of clinical

significance.

|

REFERENCES

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Management of intrapartum fetal heart rate

tracings. ACOG Practice Bulletin 116. Washington, DC; 2010.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery.

Obstetric Care Consensus No. 1, March 2014.

Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Hauth JC, Gilstrap LC III, Wenstrom KD. Dystocia: abnormal

labor and fetopelvic disproportion. In: Williams Obstetrics. 23rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;

2010:495-520.

Hobel CJ, Zakowski M. Normal labor, delivery, and postpartum care: anatomic considerations, obstetric

and analgesia, and resuscitation of the newborn. In: H acker NF, Gambone JC, Hobel CJ, eds.

Essentials of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2009: 91-118.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.