Cardiogenic Syncope Case File

Eugene C. Toy, MD, Ericka Simpson, MD, Pedro Mancias, MD, Erin E. Furr-Stimming, MD

CASE 16

A 52-year-old man with no significant past medical history is brought to the emergency center after a motor vehicle accident in which he drove into a dividing rail. He did not suffer any significant physical injuries, and he was fully awake at the time of the examination. He reports while driving on the highway he felt “dizzy” prior to briefly losing consciousness, which caused his car to swerve into the

divider. He also endorses palpitations immediately prior to the episode. His wife, who was a passenger in the car, states that he quickly regained consciousness and was not altered or disoriented after the episode. There is no evidence or report of tongue biting, urinary or stool incontinence, or convulsions of his extremities. On further questioning, the patient admits to two previous “fainting” episodes, both in his office, and both without provocation. On one occasion, he was seated, while on the other occasion he was standing and suffered a fall. He reports a similar sensation of light-headedness and palpitations prior to the second episode. After these episodes, he scheduled an appointment with his family physician but did not have the chance to attend the appointment prior to the accident. On review of systems, he complains of recent fatigue and lack of energy over the last year, but he attributes it to his hectic work schedule and lack of exercise. Physical examination in the emergency department (ED) is unremarkable, including detailed neurologic examination. His initial laboratory studies and noncontrast computed tomographyy (CT) of the head are unremarkable.

▶ What is the most likely diagnosis?

▶ What is the next diagnostic step?

▶ What is the next step in therapy?

ANSWERS TO CASE 16:

Cardiogenic Syncope

Summary: This 52-year-old man presents with an acute episode of sudden loss of consciousness (LOC) without convulsive activity or postepisode confusion, and a history of two similar episodes in the past. Prior to his two most recent episodes, including his current one, he reported feeling light-headed and felt his heart racing for a brief period.

- Most likely diagnosis: Cardiogenic syncope, likely related to arrhythmia.

- Next diagnostic step: Detailed history, physical examination including orthostatic blood pressure, and 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG). Cardiac telemetry monitoring, 2D echocardiogram, and carotid ultrasound may be indicated if the initial workup is negative and there is a high index of suspicion for paroxysmal arrhythmia.

- Next step in therapy: Review medications that might contribute to syncopal spells, and initiate additional treatment depending on suspected etiology.

- Identify common causes of LOC or syncope.

- Compare and contrast syncope versus seizure.

- Describe the evaluation for syncope.

- Comprehend the management of syncope.

Considerations

In this case, the patient suffered an acute LOC without provocation or premonitory nausea, sweating, or abdominal discomfort. He did, however, report palpitations and light-headedness immediately preceding the episode. The event occurred while he was sitting in his car, and he regained consciousness quickly. This event is less consistent with orthostatic syncope, as it was not associated with a change in position and was not associated with signs and symptoms suggestive of low blood pressure. His wife denied convulsions or postictal confusion, as well as tongue biting or bladder or bowel incontinence, which otherwise might be suggestive of seizures.

The most likely diagnosis in this patient is cardiogenic syncope, possibly related to paroxysmal atrial fibrillation or an other arrhythmia. His initial evaluation should include a detailed history, a physical examination with emphasis on the cardiac and neurologic systems, and a 12-lead ECG. Although orthostatic hypotension-related symptoms are less likely if the patient’s syncope was not related to position changes, orthostatic vital signs should be checked, including blood pressure and heart rate in lying, sitting, and standing positions.

This particular patient experienced recurrent syncopal episodes. After his initial cardiac workup was unremarkable, he was discharged home with a 30-day cardiac event monitor and was subsequently diagnosed with “sick sinus syndrome,” a disorder of the sinoatrial node or internal cardiac pacemaker. He subsequently underwent placement of a permanent cardiac pacemaker and experienced an improvement in symptoms and no further syncopal spells and improvement of his fatigue.

APPROACH TO:

Cardiogenic Syncope

DEFINITIONS

SYNCOPE: A transient, self-limited LOC episode that results from inability to maintain postural vascular tone followed by spontaneous recovery.

ORTHOSTATIC SYNCOPE: Syncope associated with a change in position from supine to sitting or sitting to standing, due to impaired compensation of vascular tone or cardiac output.

ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHY (EEG): The neurophysiologic measurement of the electrical activity of the brain by recording from electrodes placed on the scalp or, in special cases, on the dural surface.

SEIZURE: Abnormal, excessive synchronous neuroelectrical activity.

EPILEPSY: A condition defined by the presence of recurrent, unprovoked epileptic seizures.

TILT-TABLE TESTING: Test to evaluate how the body regulates blood pressure in response to changes in posture. It involves cardiac monitoring (ECG), blood pressure monitoring, and sometimes pharmacologic agents to stress the system.

SICK SINUS SYNDROME: Sinus nodal dysfunction leading to arrhythmias, including “tachycardia-bradycardia” syndrome, which is characterized by alternating fast and slow activity.

CLINICAL APPROACH

Syncope results from decreased cerebral blood flow leading to cerebral hypoperfusion. Cardiogenic syncope is caused by impaired cardiac output (cardiac output [CO] = stroke volume [SV] × heart rate [HR]), which leads to cerebral hypoperfusion. There are numerous causes of syncope.

ABNORMAL HEART RATE OR RHYTHM

HR below 35 or above 150 beats/min may cause syncope even in the absence of cardiovascular disease. Symptomatic bradycardia is a common cause of cardiogenic syncope and can be caused by medication side effects or conduction abnormalities, including heart block. Medications that slow HR, including beta-blockers, digoxin, and amiodarone, among many others, may predispose to syncope. Arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation and sick sinus syndrome, impair cardiac efficiency and may manifest clinically with syncope. Of note, atrial fibrillation is the most common arrhythmia known to increase the risk of ischemic stroke and may warrant treatment with aspirin or anticoagulation, depending on risk stratification. The presence of palpitations is worrisome for arrhythmia-associated cardiogenic syncope.

ABNORMAL PERIPHERAL VASCULAR TONE OR FLOW

Among the common noncardiogenic mechanisms of syncope are peripheral

vasodilation, decreased cardiac venous return, and hypovolemia, including venous pooling. Exertional syncope may suggest cardiac outflow obstruction, often caused by aortic stenosis and less commonly by hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM), and warrants evaluation with an echocardiogram. Syncope occurring in the setting of cough or Valsalva may suggest impaired venous return, but it also warrants consideration of neurocardiogenic or vasovagal syncope (see next). Neurovascular abnormalities, including carotid occlusive/stenotic disease or

vertebrobasilar insufficiency, may sometimes present with syncope as a sentinel symptom but may also produce focal neurologic deficits.

NEUROCARDIOGENIC/VASOVAGAL SYNCOPE

Neurocardiogenic or vasovagal syncope is thought to result from decreased venous return to the heart, leading to reflex increases in HR and contractility via carotid sinus baroreceptors (low-pressure sensor) and subsequent activation of parasympathetic left ventricular baroreceptors (high-pressure sensor). This ultimately produces the characteristic finding of hypotension with paradoxical bradycardia. Symptoms are often precipitated by unpleasant physical or emotional experiences, most commonly pain, sight of blood, or gastrointestinal discomfort. Dehydration and alcohol use are associated with worsening symptoms. Initial treatment is generally supportive, including hydration, pressure stockings, and identification and avoidance of triggers.

ORTHOSTATIC SYNCOPE

Orthostatic syncope is associated with a sudden change of posture from lying or sitting to standing or after prolonged standing without moving. Orthostatic hypotension is defined by a drop in systolic blood pressure (SBP) of at least 20 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of at least 10 mm Hg, with or without change in HR, within 3 minutes of change in position from supine to sitting or sitting to standing. Particularly in older patients, orthostatic syncope may be related to hypovolemia or increased venous pooling (functional hypovolemia). Autonomic dysfunction may also impair proper orthostatic responses. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy or acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP) has been associated with dysautonomia due to peripheral nerve involvement. Orthostatic hypotension is one of the cardinal features of multiple system atrophy, a neurodegenerative disease characterized by parkinsonism or cerebellar dysfunction, dysautonomia, and pyramidal symptoms.

SEIZURES

Syncope and seizures may be difficult to distinguish, so knowledge of characteristic clinical features of each is important. Epileptic seizures result from abnormal excessive synchronized brain electrical activity, which may or may not be associated with LOC. Seizures may be partial (originating from a focus) or generalized (involving diffuse bilateral areas of cortex). Generalized seizures, furthermore, may be primarily generalized or secondarily generalized from a partial focus. Although no one feature is pathognomonic, the following features are more commonly observed with seizures than with syncope: convulsive activity, lateral tongue biting, bladder or bowel incontinence, and postictal confusion.

Evaluation

Patients suspected of syncope should undergo a cardiac evaluation, including an ECG and measurement of orthostatic vital signs. Event monitoring either with a 24-hour Holter or prolonged monitoring for arrhythmias is often useful. High clinical suspicion for seizures or other neurologic phenomenon may warrant evaluation with EEG and neuroimaging.

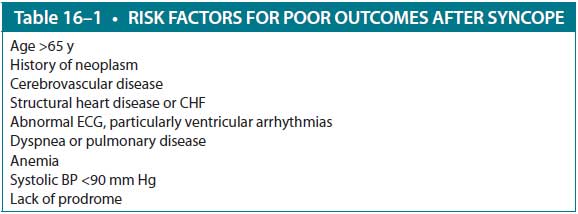

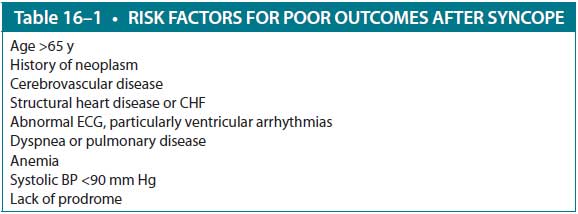

If seizures are ruled out and syncope is confirmed, patients should be stratified by risk. Patients are considered to be high risk for serious events within 1 week if they present with any of the following risk factors: abnormal ECG, congestive heart failure (CHF), shortness of breath, hematocrit less than 30%, SBP less than 90 mm Hg, history of cardiovascular disease, lack of prodrome, or age greater than 65 (Table 16–1).

High-risk patients should be admitted for inpatient workup including continuous telemetry monitoring, echocardiography, carotid ultrasound, and cardiac stress testing. High-risk patients with a negative inpatient workup may be candidates for an implantable loop recorder, which provides long-term outpatient cardiac monitoring.

Low-risk patients may be followed up on an outpatient basis. A tilt-table test may confirm a suspected diagnosis of neurogenic syncope. A prolonged Holter monitor provides ECG data and may be considered in patients with frequent episodes of syncope. An implantable loop recorder, which allows for more prolonged monitoring, may be considered if the episodes of syncope are infrequent.

It is not necessary to obtain a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain or EEG in all cases, but these tests should be considered if a cardiac etiology is elusive or if seizures or other neurologic phenomena are suspected.

CHF, congestive heart failure; ECG, electrocardiography.

Treatment

Appropriate treatment of syncope requires proper diagnosis and depends largely on underlying cause. In the case of vasovagal syncope, pharmacologic treatment often is not required. Orthostatic hypotension may be treated by volume resuscitation, compressive stockings, correction of electrolyte imbalances, and avoidance of contributing medications (eg, beta-blockers). If symptoms persist, pharmacologic treatment with midodrine and/or fludrocortisone should be considered. Midodrine is an alpha-agonist that increases vascular tone. Fludrocortisone is a synthetic corticosteroid with mostly mineralocorticoid activity, which leads to retention of sodium and increased intravascular volume. Another treatment option is droxidopa, a pro drug of norepinephrine, recently approved by the FDA for the treatment of neurogenic orthostatic hypotension. Patients receiving pharmacotherapy should be closely monitored for supine hypertension, which may increase the risk of heart disease and stroke.

Sick sinus syndrome, heart block, or other symptomatic bradyarrhythmias may require permanent pacing. Atrial fibrillation may be treated by cardioversion, rate control, and/or rhythm control, depending on chronicity and other factors. Keep in mind, however, that several pharmacologic treatments for atrial fibrillation (beta-blockers, digoxin, amiodarone) may worsen syncopal symptoms. Additionally, patients with atrial fibrillation should be evaluated for treatment with aspirin or anticoagulation to mitigate stroke risk.

CASE CORRELATION

- See Cases 14 and 15 (on Seizures)

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

16.1 A 22-year-old nursing student loses consciousness while observing a woman giving birth. She slowly falls to the ground and is caught by her colleague. Which of the following is the most likely etiology?

A. Seizure

B. Vasovagal syncope

C. Orthostatic hypotension

D. Cardiogenic syncope

16.2 A 17-year-old high school football player passes out on the field while running practice sprints. Which of the following is the most likely etiology?

A. Vasovagal syncope

B. Cardiac outflow obstruction

C. Seizure

D. Orthostatic hypotension

16.3 A 43-year-old woman with a history of previous ischemic stroke is found unconscious in her home by a visiting neighbor. She has urinated on herself, and there is a small amount of blood and saliva coming from the side of her mouth. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Cardiogenic syncope

B. Vasovagal syncope

C. Seizure

D. Orthostatic hypotension

ANSWERS

16.1 B. This is most likely caused by a vasovagal reflex (drop in blood pressure and HR) in response to painful or emotionally charged stimulus, and it is usually non–life-threatening. These are usually described as “graying out” episodes, and often the patient can feel slowly losing consciousness.

16.2 B. Cardiac outflow obstruction may lead to exertional syncope. Aortic stenosis is the most common etiology; however, HOCM should be considered in younger patients. An echocardiogram should be done for further evaluation.

16.3 C. Seizure is the most likely diagnosis given a prior history of stroke, which can predispose to a seizure focus. Seizures are commonly seen in poststroke patients for this reason. Although clinical signs such as incontinence and tongue laceration are not specific for seizure, in the context of a possible cerebral focus, seizure is the most appropriate answer.

CLINICAL PEARLS

|

▶ Syncope is defined by a sudden, brief

LOC with spontaneous recovery and is due to transient cerebral hypoperfusion.

▶ Seizures occur due to abnormal,

increased synchronous brain electrical discharge and are more commonly

associated with convulsive activity, tongue biting, bladder/bowel

incontinence, and postictal confusion. However, no one sign alone is

pathognomonic, and history and examination should dictate clinical suspicion.

▶ Orthostatic hypotension results from

impaired blood delivery during position changes and may be related to

hypovolemia, venous pooling, medications, or dysautonomia, among other

causes.

▶ Initial workup for syncope includes

ECG and orthostatic vital sign measurement. Additional inpatient workup for

high-risk patients includes telemetry monitoring, 2D echocardiogram, carotid

ultrasound, and laboratory studies. If no cause is identified, a

long-term cardiac monitor should be considered upon discharge to identify

possible paroxysmal arrhythmias.

|

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.